La Marseillaise : a song of war, a song of freedom

Sous-titre

Bernard RICHARD

To go directly to the chapter of your choice, simply click on it:

I- The concept of a national anthem II- The birth of a battle song The composer III. A battle song of dreaded effect; a song of freedom that soon spread beyond the French borders IV. A revolutionary song banned in France from 1804, except with the re-establishment of the republic V. The Marseillaise, national anthem… of the Republicans VI. An international destiny VII. The Great War, between Marseillaise and Madelon VIII. The Marseillaise in the interwar years IX. An anthem and a flag for two Frances X. Words ill received, words ill known? XI. Do parodies debase the Marseillaise? Bibliography

Vincent van Gogh. The fourteenth of July celebration in Paris, 1886.

The Marseillaise has been the French national anthem only since a law was passed on 14 February 1879, when France’s institutions passed into the hands of republicans (and since then it has remained so without interruption - except for the accidental parenthesis of an anti-republican French State, from 1940 to 1944). On 30 January 1879, the republican Jules Grévy took over as French President following the resignation of MacMahon, a staunch royalist. The choice of the anthem, with the return of the government to Paris, was the first symbolic measure, a year before 14 July was chosen as the date of France’s national day (on 6 July 1880). The anthem, composed in April 1792, was originally entitled Chant de guerre pour l’armée du Rhin (Battle song for the Army of the Rhine), and for almost the whole of the 19th century in France it was a song of struggle against conservative and authoritarian regimes. In addition, very early on the Marseillaise attained huge popularity across the world, and was sung to galvanise protesters against their oppressors in numerous countries.

I- The concept of a national anthem

The concept of a national song or anthem appeared in England in 1740 with the nationalistic Rule, Britannia!, then in 1745 with the dynastic God Save the King. A loyalist song, it was sung by the English against the Jacobite rebellion led by the ‘Young Pretender’, Charles Edward Stuart, the last Catholic pretender to the British throne. The prince landed in Scotland in summer 1745 and was defeated in February 1746. At the time of these events, God Save the King achieved a breakthrough in the press (which supplied readers with the words) and in the theatres of London. From March 1793 onwards, with the wars against revolutionary then imperial France, a dynastic, nationalistic cult developed in England, accompanied by these two songs. During their performance, a motionless and dignified standing position was adopted, men with their hats off and one hand on their hearts. France followed the same course, with a number of songs, but the Marseillaise was quick to prevail, being declared the “national anthem” (or rather “one of the national anthems”) on 14 July 1795. Under the Revolution and during the 19th century, some would kneel for the sixth verse - containing the lines “Sacred love of the motherland” and “Freedom, cherished freedom!” - a religious posture, reminiscent of that adopted in Catholic mass for a passage of the credo or the elevation of the host. Touched upon previously, in connection with these national anthems, is the idea of a “transfer of sacred function”, from religious worship to patriotic cult. We will return to that idea further on. In the yet to be unified Germany, Deutschland über alles appeared much later. How should it be translated? Germany “before all” or “above all else” (as it is usually rendered), or else “more beloved” or even “greater than all else”; the phrase is ambiguous and its translation unclear, since it is a proposition lacking a crucial element: the verb. The poem was written in 1841 by the poet and linguist August Heinrich Hoffmann (sometimes known as Hoffmann von Fallersleben, after the village of his birth). He wrote it on Heligoland, an island off the German North Sea coast, with a German-speaking population, but which belonged to the Danish from 1714 to 1807, then the British from 1814 to 1890; an island at the outermost limits of Germany, a borderland like France’s Strasbourg. In the 19th century, the song was regarded by the ruling princes as too liberal, calling on the German people to rise against them to claim their freedom. It was not adopted as Germany’s national anthem until 1922, by the Weimar Republic, only then replacing the various dynastic anthems, the Prussian anthem and the anthems of the various ruling princes, then the German imperial anthem. Much loved, it was maintained by Hitler from 1933 to 1945, alongside the purely Nazi anthem, the Horst-Wessel-Lied. It should be added that the slogan Deutschland über alles had a long history of antecedents in Österreich über alles (Austria above all else).

Yet while these two anthems are essentially British or German, there is something universal about the Marseillaise (in much the same way as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, of 1789), which is one of the reasons it stands apart from other national anthems, and is the pride of the French people. It is true that other words, in other languages, have been set to the melody of God Save the King, thought to date from the 16th or 17th century - for instance, to celebrate American independence, a king of Denmark or Prussia, various German princes and Swiss cantons, and even a Russian tsar. But these were only fleeting, marginal episodes, nothing comparable to the popularity enjoyed by the Marseillaise outside France.

In addition, it is referred to as “the national anthem” in Section One of the French Constitution of 1946 (and reiterated in the Constitution of 1958), between “the national emblem” and “the motto of the Republic”.

II- The birth of a battle song

We know that, inspired by circumstances, the Chant de guerre pour l’Armée du Rhin, dédié au maréchal Luckner (Battle song for the Army of the Rhine, dedicated to Marshal Luckner; Luckner was a Bavarian army officer in the service of France since 1763, of whom one minister said, in 1792, “his heart is more French than his accent”) was composed in the frontier town of Strasbourg, on the night of 25 to 26 April 1792, after an evening spent at the home of the mayor, the enlightened industrialist Dietrich. It happened in a France in revolution and threatened by invasion, while the legislative assembly had just declared war, on 20 April 1792, on Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia and Hungary - and brother of Marie-Antoinette. The motherland was in danger, as it was soon declared to be (on 11 July 1792). Patriotic exultation and revolutionary fervour stirred up the country, civilians and soldiers, children and adults alike. For instance, large numbers of messages and petitions were sent by schools to the legislative assembly between April and July 1792 (Louis Lumet, Les écoles en 1792 et en 1914-1917, Paris, Éditions de Boccard, 1917). Soon volunteers flocked to defend their country and its new institutions.

For various reasons, Rouget de Lisle was - and still is - contested as the lyricist and, above all, as the composer of the Marseillaise. Much doubt has been cast over his qualities as a poet - described by some as “mediocre” - and, in particular, over his musical abilities, in the light of his earlier and later works. The fact that he had only one masterpiece to his name supports this scepticism. Suspicions were also favoured by the circumstances: how was it possible that in a single night of feverish excitement, a man known to be an amateur rather than a professional could have written a work of such perfection, a song whose musical and lyrical magic has “made the world sing”, as the composer himself put it just before his death?

It is true that, in his lifetime, “the engineers officer’s authorship was never seriously contested”, writes Michel Vovelle (p. 91), even if his name does not always appear on the many handwritten and printed scores which circulated in France. It is also true that, in the first months, not everyone knew the name of the composer of this song, so rapidly - practically immediately - disseminated around the country.

The words, at least those of the first six couplets, are generally attributed to him, barring perhaps a few small amendments made in the first few months.

However, in the 19th century and up to the present day, critics have asserted - and even claimed they could prove - that the music was not Rouget de Lisle’s work, but had been plagiarised from an earlier or contemporary composer. Following the composer’s death (in 1836, in Choisy-le-Roi), the claims began to multiply, involving, for instance, various Germans - due to rising tensions around the Rhine crisis of 1840. It is claimed that the inspiration for the Marseillaise came from a theme in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No 25 in C major, or from another piece of music by one of the sons of Johann Sebastian Bach. Since there are only seven notes (as Saint-Saëns purportedly said, according to Michel Vovelle), it is not impossible that themes found in one piece should be used in others, consciously or otherwise. But in 1842, the newspaper Karlsruher Zeitung asserted that the work was of German origin, having been written by a composer named Alleman, whom no one had ever heard of. Six years later, in 1848, the Leipzig music gazette Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung presented a Rhine Jacobite by the name of Forster as the author of the words, which he set to music by Reichardt (who, still alive, denied the claim on several occasions). The same year, the Cologne newspaper Kölnische Zeitung claimed it was an old work discovered by an organist at Meersburg called Hamman or Hamma. Claims as to the piece’s German origin, either as a work by a named composer or as a traditional song, were frequent up until the turn of the 20th century. In Austria, the work is often attributed to Ignace Pleyel, who in September 1791 had written the music for a poem by Rouget de Lisle, Hymne à la Liberté. Yet the fact that Ignace Pleyel had set himself up as a piano-maker in Paris several months prior to April 1792 did nothing to stop the story from being circulated - as it still is today - in Vienna. But the French-speaking world was not to be outdone. In 1863, the director of the Brussels Conservatoire, François-Joseph Fétis, revealed a new composer of 1792: “citizen Navoiville”; but the following year Fétis himself put paid to this theory, after it transpired that the manuscript he had based it on was a fake. In France, too, a number of composers have been put forward. For instance, in 1784 (or 1787), the choirmaster at Saint-Omer Cathedral, Jean-Baptiste Grisons, is said to have written an oratorio, Esther, based on Racine’s tragedy, in which the tune of the Marseillaise can be recognised almost note for note (an assertion reiterated in 1974 by Philippe Parès in Qui est l’auteur de la « Marseillaise » ?, Paris, Éditions Minerva). But the work appears to be misdated and was actually composed later (in 1793), and its composer used the popular tune of the Marseillaise precisely as a way of showing his support for the new regime. Hervé Luxardo, one of the recent historians of the anthem (Histoire de la Marseillaise, Éditions Plon, collection Terres de France, 1989) devotes a whole chapter to the question (chapter V, ‘Les pères de la Marseillaise’). He writes: “Many historians, critics and musicians, eager to make their mark, have tried, in vain, to demonstrate that the composer of the Marseillaise could not have written it.” Several years earlier, in 1984, Michel Vovelle, an authority on the history of the French Revolution, was equally definite in his refusal of the German claims of the 1840s: “the beginning of a stream of assertions that would go on until the end of the century, and would not see the work of Rouget de Lisle returned to its author until the pen of the irrefutable Julien Tiersot finally did so. This posthumous dispute over the authorship of the Marseillaise, originally uncontested, sheds some light on what an important issue it has become.” (Michel Vovelle, ‘La Marseillaise. La guerre ou la paix’, pp. 85-136, in Les lieux de mémoire, I. La République, ed. Pierre Nora, Éditions Gallimard, Bibliothèque Illustrée des Histoires collection, 1984.) We will not go back over this question, since it has been resolved by “the irrefutable Julien Tiersot” (Rouget de Lisle, son œuvre, sa vie, Éditions Delagrave, 1892, followed up in Histoire de la Marseillaise, Delagrave, 1916), along with two of his contemporaries, the musicologists Constant Pierre (Les Hymnes et chansons de la Révolution française, Imprimerie Nationale, 1904) and Louis Fiaux (La Marseillaise, son histoire dans l’histoire des Français depuis 1792, Éditions Fasquelle, 1918). Recently, however, the violinist and musicologist Guido Rimonda asserted that fellow Italian Giovanni Battista Viotti was the real composer of the work, in 1781. Here again, the manuscript and its date need to be studied carefully, since each one of those previously claimed to be the real composers of the Marseillaise were found subsequently to have composed their works after it, inspired by it, and were used by others to serve nationalist or political interests, with the additional intention of shaking up, not to say pulling down, established certainties. Let us not draw any conclusions, for the challenges to Rouget de Lisle’s authorship of the Marseillaise, both in respect of the tune and the words, have been a frequent occurrence since the 1840s, both in France and abroad. The sacred engenders sacrilege, and holy relics proliferate: the sacred anthem of the Marseille folk toured Europe much like the relics of St Mary Magdalene.

There have been fewer disputes over the words, but they have nonetheless existed. References have often been made, following the erudite Julien Tiersot (Histoire de la Marseillaise, Paris, Éditions Delagrave, 1915, p. 37), to slogans and proclamations found on posters around Strasbourg, yet there is no evidence of such proclamations in the archives. Whether it is the battalion Les enfants de la Patrie, in which two sons of the mayor of Strasbourg are said to have served, or posters neither archived nor preserved, bearing slogans like Take up arms, citizens!, March on! and The war banner is unfurled!, Jean Jaurès, in his Histoire socialiste de la Révolution française, wrote that the words of the Marseillaise were dictated to Rouget de Lisle “by the people”: “The truth is that this song was not the work of one man; he did little more than dress up and set to a lively rhythm the words of anger and hope which for several months had flowed from people’s hearts across France.” So be it! At bottom, whether it’s the Marseillaise or God Save the King, the origins and sources of the words and music are of little consequence; what matters is how this “battle song” was immediately embraced as a revolutionary song throughout France, how rapidly it entered the “national narrative” and how it was adopted as a rallying symbol by the supporters of revolutionary ideas in France (Strasbourg, Montpellier, Marseille, Paris), then across Europe.

How to reconcile the legendary speed with which the words and music were purported to have been written - in one feverish night, 25 to 26 April 1792 - with the quality and lasting nature of the work, and the admiration it inspired from early on, and for so long? Question marks must be allowed to remain, regarding the music more than the words. Yet it is worth remembering that it was Rouget de Lisle’s body which left the cemetery of Choisy-le-Roi, on 14 July 1915, to be received at the Hôtel des Invalides by President Poincaré.

The Marseillaise, a military march born in France’s borderlands, was quick to play an important role in French civilian and military life, and its versatility ensured its vocation as an anthem for many other nations. Right up to the present day, it has been used by many peoples fighting for freedom (except, for obvious reasons, the former French colonies). Perhaps the one major regret in Alsace, and for the composer himself, a native of Franche-Comté (in whose home town of Lons-le-Saunier the chimes of the theatre play the first bars of the chorus several times a day) is the name Marseillaise, when it might equally well have been the Strasbourgeoise! It is a song against tyrants and despots, in other words, against outside aggressors or governments held in contempt, considered illegitimate by the population or a sector of it. A song of freedom, the words of the sixth verse are addressed directly to Liberty, in a famous line which would later serve as the title for the memoirs of French politician Pierre Mendès France: “Liberty, cherished Liberty! / Join the struggle with your defenders!”

The tone, music, rhythm and “manly strains” of the piece give it great resonance when accompanied by drums and trumpets, making it a rousing marching song to be played to the sound of cannons, an air to be sung in chorus, out in the open air. Its lively pace inspires enthusiasm, bolsters combatants’ morale, galvanises the troops. Its words, in the formal, classical style of the period, are pompous at times; but the words of the chorus, doubtless inspired by short proclamations or slogans written by patriots (for instance, “Take up arms, citizens!”), are easily comprehensible and for everyone to join in. Moreover, this simple military refrain can be sung with or without instrumental accompaniment, whereas some of the verses present real difficulties for performers. Like all popular songs, the Marseillaise adopts the division couplet/refrain, a refrain easy to memorise, and therefore easy for a group or crowd to join in. The musical appeal of the Marseillaise, and its “galvanising”, electrifying power, have contributed to its lasting success. So there are concrete musical reasons why this anthem, more than any other, has the power to unite voices and minds. They are presented in an as yet unpublished study by Yves Audard, regional inspector of music for Burgundy, sections of which are quoted faithfully below. The study addresses the rhythm, melodic structure and harmony (i.e. the chords underlying the rhythm and melody) which give the piece its lively, military character. From the first bars, it is capable of rousing a crowd or an army. With a musicologist’s skill, Audard shows how “the Marseillaise is not just any piece of music; it is a work which has been carefully thought out and ‘composed’. It is an authentic musical work, which draws on classical music and uses all the processes made available by the advances in musical language of the period”. This raises the question of its composition, said to be in a single night, yet resting on firm musical foundations that have matured over time. Once again, according to Audard, “here are musical processes borrowed from classical music. Rouget de l’Isle - if he really is the composer of this march of the Marseille folk - knew the tricks of his trade and how to use them, much the same as Gluck or Méhul!” This phrase is borrowed from Madame de Dietrich, wife of the mayor of Strasbourg, who is supposed to have said, “It’s like Gluck, only better.”

At least for the first couplet and the refrain - often the only ones known and sung - the link between text and music is close, even integral. A crowd or an army sings with ease this lively anthem, for the most part restricted to the reach of a normal voice, i.e. one octave, with the exception of the last line of the chorus (“May our land with tainted blood be soaked”), which reaches up to a higher note. In addition, the tone of the Marseillaise is based almost entirely around perfect chords. All these musical elements contribute to explaining how rapidly it spread across France and beyond, and how it has remained popular.

The fact that it was brought to Paris in July 1792 by volunteers from Marseille who had come to defend an endangered motherland, then sung on 10 August 1792 at the storming of the Tuileries Palace, when the monarchy was overthrown, gives it strong revolutionary roots that add to its origins as a battle song.

Of course, it is neither the first nor the only revolutionary song of its period in France. Some time before, in 1790 or even 1789, the simple and popular Ça ira, set to the tune of Carillon national, a new and bouncy quadrille for violin which could be adapted to all circumstances because of the ease with which new couplets could be created; accounts tell how it gave courage and spirit to those setting up the Champ de Mars, in the rain, for the first Festival of the Federation, in June-July 1790. Another popular song, said to have been brought by workers or craftsmen from Piedmont or Provence, in 1792, was the Carmagnole, another dance, this time a farandole, which was sung at the Tuileries after 10 August 1792. Both these songs enabled new couplets to be added and were potential rivals of the Marseillaise. But their register was too popular, too simple, too close to the village dance to compete with it in more serious and solemn circumstances; they were also lacking in fighting spirit to cater for the need of the moment, when France in revolution was threatened by adversaries from within and without. As for Chant du Départ, written by Marie-Joseph Chénier (words) and Méhul (music) in 1793, it was played in public on 14 July 1794, shortly before 9 Thermidor; in fact, it almost certainly arrived too late, when the place had already been taken and secured by the Hymne des Marseillois. It was indeed the Marseillaise that was sung at the Battle of Jemmapes in November 1792, but its presence at the Battle of Valmy, on 20 September, belongs to the domain of legend; the only certainty is that Ça ira was sung there, with or without the Carmagnole, the Marseillaise not being sung until a few days after the battle, to celebrate the victory.

The song spread very quickly, and by July 1792 it had become known as the Chant (also Marche, Hymne or Chanson) des Marseillois, because it had been brought to Paris by volunteers from Marseille, who sang it as they marched to defend the “motherland in danger”. It soon also earned the positive epithets of “the patriots’ cherished tune”, “ode to Liberty” and “the sacred hymn of the Marseille folk”, the latter a somewhat hasty canonisation (the French word hymne, in the masculine, meaning an ode or anthem, but when used in the feminine, as here, refers to a religious hymn, as if expressing a sanctification or religious kind of veneration for this military song, soon to become the “national anthem”). When, in 1796, Rouget de Lisle had his Essais en vers et prose published by Didot L’Aîné, he gave the work the title Le Chant des Combats, vulgairement l’Hymne des Marseillois (The Song of Combat, commonly known as the Anthem of the Marseille Folk). He used the latter title in a new edition of his works in 1825. Thus, even the composer himself could not get away from Marseille, opting as he did for the title adopted by the Parisians in July 1792.

In France itself, the Marseillaise became a fixture at all the revolutionary events from 10 August 1792 onwards. An arrangement by Gossec, for a dramatic work entitled L’Offrande à la Liberté (The Offering to Liberty), including choir, recitative, etc., was presented at the Paris Opera on 30 September 1792, and frequently performed under the Revolution (120 times between September 1792 and September 1795). A new arrangement was made by Méhul in 1795, when the Marseillaise became the “national anthem”; and in November 1830, it gained a further arrangement for symphony orchestra, with copious brass and percussion, by Hector Berlioz, who described in his Mémoires the powerful impression made on him during the July events by “the music, the singing, the raucous voices that rang out in the streets”. Gossec, Méhul, Berlioz: so many arrangements to form part of the classical repertoire for formal occasions, and the music of Rouget de Lisle lent itself well to such settings.

The title of the anthem, very variable in the beginning and, as we have seen, most commonly Hymne (or Chant) des Marseillois progressively became La Marseillaise, a title which would dominate only from the 1830s onwards.

The monumental staging of L’Offrande à la Liberté, sometimes described as an “opera” or even as “religious drama”, sees a feminine allegory of Liberty (statue or actress) before whom actors, choir and audience kneel respectfully, religiously, for the sixth couplet, “Sacred love of the motherland”, followed by “Liberty, cherished liberty”. This was the germ, the origin of the future female incarnation of La Marseillaise, the original trait of the French anthem.

III- A battle song of dreaded effect; a song of freedom that soon spread beyond the French borders

Certain characteristics of the song’s lyrics favoured its vocation as a universal anthem, to be used by all nations, at least over a period stretching from the French Revolution to the Second World War.

It is a patriotic song against the enemy, whose text is strongly idealogical yet does not explicitly state either who the motherland is or who the enemy is (“Sacred love of the motherland etc.”).

A rousing song with a marching pace, directed against the tyrants and in favour of Liberty, the Marseillaise was already firmly established by 1794. Moreover, outside France, it could be easily adapted, and was straightforward to translate and transpose: over seven verses, the word Français only appears twice, in the little sung second and fifth verses, and it could be easily replaced without changing the spirit of the song, while the motherland (Patrie) is exalted in the chorus and in one verse, without being identified by name. By contrast, Deutschland über alles, composed in 1841, includes, in three couplets, fourteen instances of the word Deutsch or Deutschland. The adaptability of the words of the Marseillaise led to countless adaptations, at a time when it was common practice to take a well-known tune and set new words to it, by either completely or partly altering the original, and a melody was all the more frequently used if it was well-known and popular, an added advantage for the Marseillaise, which became popular early on and had excellent musical qualities for a march. Under the Revolution, at least one in twelve such adaptations, or hijackings (the technical term is contrafactum; not to be confused with the word ‘counterfeit’, which shares the same Latin root), took the tune of the Marseillaise, or Marseillois, as it was more commonly known at that time. Many other songs had been and would be used in the same way, albeit to a lesser degree, including the Carmagnole, of which more than fifty versions are known. And this would continue throughout the 19th century and on into the 20th, with for example, around 1880, the Carmagnole des Syndicats, or ‘Carmagnole of the Unions’, by one T. Quillent (“Long live the trade unions! / Go to it, lads! / Let us organise / A general strike / And we shall triumph / Over the bosses!”) , or the Carmagnole des Mineurs (‘Carmagnole of the Miners’), by François Lefebvre, founder of the first miners federation in northern France (“Long live the miners’ union! / Down with all these exploiting villains! / Long live the social, democratic Republic! / Long live the Republic! / Long live the sound…”). It is worth remembering that, at that time, it was commonplace for melodies to be hijacked. For instance, most of prolific early 19th-century French songwriter Pierre-Jean de Béranger’s songs were subtitled with the words “to the tune of...”(e.g. “Le Roi d’Yvetot, to the tune of Quand un tendron vient en ces lieux”); this practice was not new, and it would go on for years to come.

In France, musicologist Constant Pierre (Les Hymnes et chansons de la Révolution, 1899 and 1904) identified more than 170 different versions of the Marseillaise in the revolutionary period alone, with a Marseillaise of the people of Lille, Caen, Brittany, Lons-le-Saunier (Rouget de L’Isle’s home town) and many other towns, regions or occasions, such as the Marseillaise of the farmers, of the women, and so on. Since then, German researcher Hinrich Hudde, perhaps the leading authority today on the French anthem in the period 1792-1830, has identified around 240 versions, including some 20 hostile “counter-Marseillaises”, like the Marseillaise des Poitevins, from 1793 (“Take up arms, people of Poitou! / Form your battalions / March on, march on / May your land be soaked with the blood of the Republicans!”), or Abbot Lusson’s Contre-Marseillaise ( “Come, Catholic armies / The day of glory has arrived / Against us the Republic’s bloody standard is raised.”) In France, the vast majority of adaptations/hijackings during the revolutionary period were sympathetic to the new spirit. Two-thirds of the works identified were written between July 1792 and July 1794, including the Marseillaise de l’Égalité retrouvée (Marseillaise of Refound Equality), written and sung in the Occitan language in the Landes, for an edition of the Festival of Reason (transcription and translation by Guy Latry in Les Landes et la Révolution, Éditions Conseil Général des Landes, 1992, cited by Frédéric Dufourg in La Marseillaise, p. 78-79, 2003, Éditions du Félin).

Abroad, direct, literal translations were first to appear, prompted either by local revolutionaries or by enemies of the Revolution, intrigued and curious to penetrate the secret of a fighting song so effective at galvanising the troops; just like the desire, a century later, to discover the secret of the 75mm or 120mm field gun.

In November 1792, we find a first translation into English and two into German; they would be followed by translations into all the languages of Europe, from Spanish to Hungarian, Polish, Swedish and Russian, with nearly ten different English translations appearing between 1792 and 1810.

In addition came the foreign adaptations, where the tune of the Marseillaise was used as the setting for new words fitting local circumstances. We know of many in German and Italian, for instance, mostly written by or for local supporters of revolutionary ideals, to convert or galvanise their fellow citizens; among these works “in the style of” were a smaller number of Marseillaise parodies, written by foreigners wishing to mock or provoke the French.

The Bürgerlied der Mainzer (Song of the Citizens of Mainz) was quite a famous German song, set to the music of the Marseillaise. Sympathetic to the French liberators, its lyrics read:

Come, my brothers, come!

Liberty smiles upon us!

The chains are broken,

Custine has freed us.

Oh, citizens, we are free!

No longer shall any despot oppress us,

Nor empty our pockets.

Mainz is free! (repeat)

The idea that the Marseillaise had an effective, direct impact on the success of French troops during the Revolution has often been emphasised; from that time forth, it became an emblem that acted directly on the event.

Here are a few examples:

One general, in a report to the Directory in 1796, requested “a reinforcement of a thousand men or an edition of the Marseillaise”. Another declared, “I have won the battle; the Marseillaise was in command.” Still another said, “Without the Marseillaise, I would fight two against one; with the Marseillaise, I would fight four against one,” while a battalion of volunteers described it as “a funny tune; it’s as if it had moustaches.” Lazare Carnot, the “Organiser of Victory”, stated in a report to the Committee for National Security in 1794 that “the Marseillaise has given the Motherland 100 000 defenders”.

Conscious of the role it played against internal and external enemies, the Thermidorian Convention declared it a “national anthem”, by the decree of 26 Messidor Year III (14 July 1795).

IV- A revolutionary song banned in France from 1804, except with the re-establishment of the republic

Each new regime in the 19th century adopted its own national or dynastic anthem - a kind of counter-Marseillaise - just as Liberty and her cap were replaced by the effigy of the new sovereign accompanied by an eagle, fleur-de-lis, Gallic cockerel, and so on.

Under the First Empire, it was Veillons au salut de l’Empire, a song of liberty composed in 1792 against despotism and the tyrants. It was now played, but its dangerous words were not sung: “Liberty, liberty, let us rally to this sacred name...” proclaims the refrain, and this was “the empire of liberty”. Various military marches can be added to the list, including Marche de la garde consulaire à la bataille de Marengo. But the Marseillaise makes a spontaneous reappearance on the battlefield at difficult times when the troops need galvanising, e.g. Napoleon’s withdrawal from Russia, the 1814 campaign and Waterloo.

Under the Restoration, both theMarseillaise and Veillons au salut de l’Empire were banned, being regarded as seditious. Republicans or Bonapartists (at the time, often one and the same) who defied the ban, for instance at the funerals of important republicans, were sentenced to months in prison. Out of defiance, it was the Marseillaise that was sung by supporters of the Republic or the Empire, especially at the King’s Feast, the Feast of St Louis, and later the Feast of St Charles; in addition, the Bonapartists created their own version of the anthem, the chorus of which ended “March on, march on, let us avenge Napoleon!” The restored monarchy created its own anthem, Vive Henri IV, which would not leave much of a mark on people’s memories, although it did briefly find favour with some, at a time when the Bourbons relied on the popularity of “Good King Henry”, whose statue, destroyed after 10 August 1792, was soon re-erected on the Pont-Neuf.

When, under the Restoration, composer Daniel-François-Esprit Auber inserted an extract of the first bars of the Marseillaise into the music of an opera by Scribe and Delavigne, it was received with such enthusiasm that there were fears of rioting. And when, believing themselves to be exorcising and at the same time harnessing the subversive power of the revolutionary anthem, missionaries had their congregations sing hymns set to the tune of the Marseillaise, with words that were Catholic and royalist to the core - a kind of “in the style of” - a prefect became worried about the memories these military sounds might awaken and the movements of enthusiasm they might arouse.

In mid-July 1830, the expulsion of a student from the École Polytechnique for singing the Marseillaise at an undergraduate dinner contributed to persuading his fellow students to join the side of the rioters in the July Revolution. Delacroix’s painting illustrates the important role played by those students on the Three Glorious Days (27, 28 and 29 July 1830). Under the July Monarchy, established by a revolution conducted to the sound of the Marseillaise, the anthem was permitted in the beginning, accompanied by the tricolour flag. In those early days, in order to win acceptance from the heroes of the Revolution, Louis-Philippe would sing it from the balcony of the Royal Palace, almost on demand, his eyes raised to the sky and his hand on his heart; then he would have it played by the Tuileries Palace guard, during which he would hum it or “pretend” to sing it, as Charles de Rémusat wrote. He even awarded Rouget de L’Isle the Legion of Honour and a modest pension, which prevented the composer from dying in poverty (in Choisy-le-Roi, in June 1836).

But the Marseillaise was above all sung at riots and demonstrations by republicans, often with a contingent of students from the École Polytechnique, as was the case of the Parisian rioters of June 1832 and April 1834; it was the Marseillaise, too, that was sung at Clamecy (Nièvre), in April 1837, when log drivers rose in revolt and the authorities had to send four squadrons of hussars to quell the rioting, and here there was no hesitation as to the anthem’s intrinsic hostility to the regime: the men and women who sang it, and who briefly took over the town hall, wore red ribbons as a sign of recognition and protest (Jean-Claude Martinet, Clamecy et ses flotteurs : de la Monarchie de juillet à l’insurrection des « Marianne », 1830-1851). In Toulouse, in November 1841, the Marseillaise was sung by prisoners locked up during the tax riots, as they were transferred from one prison to another (Jean-Claude Caron, L’été rouge).

Meanwhile, in July 1833 it was abandoned by the regime and replaced as “national anthem” by the Parisienne, a patriotic song by romantic poet Casimir Delavigne, to the glory of the martyrs of July 1830, set to music by Auber: “Brave people of France / Liberty opens its arms once more...” This new anthem’s inclusion in the official ceremonies in place of the Marseillaise met with scant approval. However, it was taken up by the rioting crowds of Parisian craftsmen and students in the February Revolution of 1848, who spontaneously made it their own and sang it alongside the Marseillaise, though seeing it as a complement to the latter, rather than a replacement.

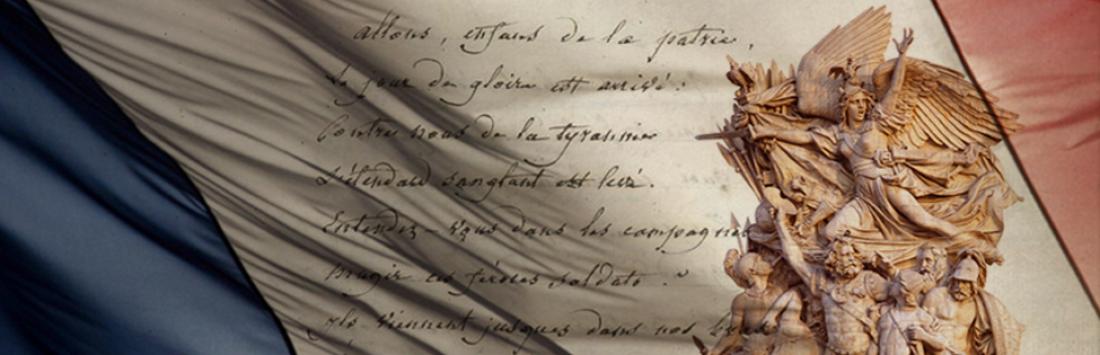

When, in July 1836, the Arc de Triomphe and its reliefs were finally inaugurated, the one entitled Le Départ des Volontaires (The Departure of the Volunteers) - dominated by the Génie de la Guerre, or ‘Spirit of War’, a winged female Victory figure wearing a Phrygian cap - was nicknamed La Marseillaise, out of defiance towards a regime that had moved away from its founding values. Rude’s sculpture undoubtedly played a major role in the subsequent development of the Marseillaise as a winged female wearing a Phrygian cap, in a visual, feminine incarnation of the “beloved anthem”. From then on, the Marseillaise was frequently personified as a Victory figure flying above the combatants. Victor Hugo’s Les Châtiments, written under the Second Empire, contains the line “The winged Marseillaise flying amid the bullets…”. It is an image found frequently during the First World War, in patriotic posters and postcards.

What other national anthem is personified in this way, either in male or female form? None. And the erudite German Hinrich Hudde explains how this allegory came into being, from the “religious scene” played out under the Revolution, with the allegory of “Liberty, cherished Liberty”, to Rude’s Marseillaise on the Arc de Triomphe. In France, the only other anthem to be represented, however infrequently, by a female figure - that of a free woman, reflecting the early women’s movements of the late 19th and early 20th century - was the Internationale, admittedly prior to becoming the official anthem of the Soviet Union. As it happens, the text of L’Internationale, written by Edouard Pottier long before it was set to music, is said to have been originally intended to be sung “to the tune of the Marseillaise”, which can easily be done.

Under Louis-Philippe, the Marseillaise, soon abandoned by the new government, would occasionally reappear, for instance when the king, or his eldest son Ferdinand, Duke of Orléans, sang a short passage from it, in 1837, before students of the Saint-Cyr military academy. In the 1830s, on hearing his anthem sung by demonstrators, Rouget de Lisle is said to have exclaimed: “Things don’t look good: they’re singing the Marseillaise.” In any case, he had been, and remained, ideologically in favour of a constitutional monarchy: he was a Monarchien, a man of 1789, not 1793, nor a Bonapartist for that matter; he clashed with Napoleon Bonaparte, too, arguing against his life Consulship, which he saw as a corruption of liberty.

It was sung at a formal ceremony at a theatre in Strasbourg in December 1839, when the body of the staunch Republican General Kléber was transferred from the cathedral to the underground tomb beneath the square where two years later his statue would be erected. It was sung by the officials during a brief period of patriotic fever, in 1840, when the Thiers government gave France’s support to the Pasha of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, and was threatened by Britain, Russia and Prussia. But it was only a passing fad: Thiers was replaced by Guizot and once again the Marseillaise was abandoned as the official anthem. Only supporters of reform or more radical change risked singing it, and they were punished for doing so; it was sung on 28 July 1840 by Republican demonstrators in the Place de la Bastille, at the inauguration of the Colonne de Juillet, in which the king, wary after the attempt on his life in 1835, did not participate. In December 1840, it was once again sung with fervour on several consecutive nights in Paris, by a crowd preparing to receive the ashes of the Emperor, then at Invalides on 15 December, at the funeral ceremony itself. Upon hearing it from her home, the Hôtel Biron (today the Rodin Museum), Madeleine-Sophie Barat, founder of the Congregation of Ladies of the Sacred Heart, became alarmed, for the song recalled the fearful years of 1792-93, which she had lived through in her birthplace of Joigny (Bernard Richard, Madeleine-Sophie Barat, sainte de Joigny, Yonne, et sa communauté dans le monde). In 1840, it was a song that filled some with enthusiasm and others with fear.

The Revolution of February 1848 also took place to the sound of the Marseillaise: it was sung on 23 February by rioters carrying the first dead from the fighting, from Boulevard des Capucines to the Colonne de Juillet; it was sung in Bordeaux on the evening of the 24th at the announcement of the events in Paris (“Young people sang the Marseillaise at the Theatre,” told one dismayed notable); and it went on to be played and sung at official occasions from February 1848 until the coup of 2 December 1851. In particular, it was solemnly and piously performed at a Parisian theatre, between March and May 1848, by the actress Rachel, dressed in a white tunic and brandishing the tricolour flag, like a new Goddess of Liberty of Year II: standing there singing the Marseillaise, in the attitude of Delacroix’s Liberté or the Arc de Triomphe sculpture, at that moment Rachel herself became a Marseillaise, the very personification of the anthem.

Rachel singing the Marseillaise

Similar theatre performances were seen during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) and the First World War; at such occasions, which fired audiences with patriotic enthusiasm, the Marseillaise often overflowed from the stage to the gallery and stalls.

The soon-to-be famous painting by Isidore Pils (son of the orderly of Marshal Oudinot), entitled Rouget de L’Isle singing the Marseillaise for the first time at the home of Dietrich, mayor of Strasbourg, was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1849. It was, according to Michel Vovelle, “one of the major pictures of the Republican imagination”. While we should not expect to find in it the faithful reproduction of a historical scene, it is nonetheless, alongside François Rude’s Marseillaise, by far the best-known, canonical depiction of the anthem’s first performance.

Isidore Pils’s painting (1849, in Strasbourg since 1919)

The work was reproduced and widely disseminated in the form of engravings, lithographs and Épinal prints by the Republicans under the Second Empire, then in school textbooks in the 1880s, while frequent permission was given by the governing board of the École des Beaux-Arts for the walls of town halls and other public buildings to be decorated with copies of the painting. The picture ultimately became a symbol of the Republic, the Motherland and the “lost provinces”. As such, it was given to the city of Strasbourg in 1919, where today it is one of the jewels in the crown of the city’s history museum. Like Kléber’s statue, it is an icon of France in Alsace and Alsace’s involvement in the Revolution.

In 1851, Baudelaire, in his foreword to the second volume of Pierre Dupont’s Chants et Chansons, describes the Chant des Ouvriers (1846) as a “workers’ Marseillaise”, a common metonym for all fiery songs.

In late 1851, resistance to the coup of 2 December, both in Paris and in the provinces, often involved singing the Marseillaise.

Banned under the Second Empire, it was replaced by a patriotic song whose every other couplet appealed for divine protection (“Almighty God of our forefathers / Come to our aid...”) and which was sung to the tune of Partant pour la Syrie, a “troubadour”-style song about the Crusades, whose official title was Beau Dunois; the music to the song is said to have been composed by the Emperor’s mother, Queen Hortense, in 1809 or 1810, with or without the help of her harpist, Pierre d’Altimare, or possibly the composer Méhul. In 1870, in his Napoléon III, sa vie, ses œuvres et ses opinions, Republican historian A. Morel sneeringly described the piece as “a bland, sickly-sweet composition, impregnated with the smells of boudoir pomade” (A. Morel, Napoléon III, sa vie, ses œuvres et ses opinions).

The ban was apparent even in the all-but-official Paris guide published in 1867 for the many provincial and foreign visitors expected for the international exposition: the guide was careful not to call the plate of François Rude’s relief sculpture on the Arc de Triomphe by the name La Marseillaise, as it had been popularly known since 1836, nor by its official name, Le Départ des Volontaires, but, curiously, as Le Chant du Départ (Paris Guide, par les principaux écrivains de France, Librairie Internationale, Première Partie, La Science, L’Art, p. 652).

Rude’s La Marseillaise, on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris

Republican demonstrators often sang the Marseillaise, for instance at the burial of sculptor David d’Angers in 1856, or that of songwriter Pierre-Jean de Béranger the following year. In 1869, the song’s provocative name was symbolically chosen as the title for journalist Henri Rochefort’s newspaper; previously, Rochefort had written in La Lanterne (a newspaper which was quick to be banned): “France has a population of 36 million, not to mention its discontents.” In January 1870, Victor Noir, a young journalist for La Marseillaise, was on his way to act as a witness in a duel, when he was killed at point-blank range by Pierre Bonaparte, a prince renowned for his violence, son of Lucien Bonaparte and therefore cousin of the Emperor. Noir’s burial in Neuilly-sur-Seine (the place of his murder) was attended by more than 100 000 people, and an angry crowd singing the Marseillaise tried repeatedly to carry the coffin away to Père Lachaise cemetery, in what was the biggest public demonstration of hostility towards the regime. Rochefort, soon after the event, wrote in La Marseillaise, “I made the mistake of believing that a Bonaparte could be something other than a murderer”, for which he was sentenced to several months in prison and his new newspaper was banned.

Still banned, the Marseillaise was nevertheless permitted by the imperial government in Paris during the period of patriotic exultation that followed France’s declaration of war on Prussia, in July 1870. By public request, on 21 July it was sung on the stage of the Paris Opera by the singer Marie Sasse, dressed in white and brandishing a tricolour flag; once the deafening cheers had subsided, the entire audience stood and listened in contemplative silence, as if she were a living allegory of the Marseillaise. It was a repeat of Rachel’s performance after the Revolution of 1848. The anthem went on to be occasionally sung and played by the imperial army during the Franco-Prussian War, when the troops needed rallying.

But at Sedan, after Napoleon III’s capitulation, the captured French soldiers were forced, in an act of humiliation, to parade before a Prussian marching band as it played the Marseillaise in the shrill tones of its fifes. Paul Bert, a member of parliament for the Yonne who witnessed a similar episode in Auxerre in October 1870, recalled the bitter humiliation in a speech in October 1880:

“We saw them, right here in this square; and we heard them, with their shrill fifes, jeering at us and insulting us, as they whistled our sacred national anthem, the immortal Marseillaise. They had plenty of time to learn it, for our forefathers taught it to them, with the tips of their bayonets, from Valmy to Auerstädt to Jena!” Of course, we cannot be sure that the Marseillaise was sung at Valmy, but it forms an integral part of the “national narrative” concerning that first victory of the French volunteers over the highly professional Prussian army. In his poem Silence à la Marseillaise, Paul Déroulède, too, evokes the debasement of the anthem at Sedan by the victorious Prussians:

Oh, ill which nothing can efface!

Oh, ill which nothing can abate!

The Prussian bugle played the Marseillaise!

The Marseillaise was sung all across Paris on 4 September 1870, when the Republic was proclaimed, as well as by the armies of the Government of National Defence. But it was banned once again from all official ceremonies under the “Republican” governments of Thiers (February 1871 to May 1873), then Marshal MacMahon (until 30 January 1879); the regime, which oscillated between republic and monarchy, did not want to make its official anthem a song still strongly associated with its revolutionary origins and its later adoption by the Paris Commune. In fact, the tune sung by the Communards was essentially the same, but with different words. In the book La Chanson de la Commune, by Robert Bercy, a major authority on revolutionary songs from the French Revolution to the present day, are four adaptations of the song, not to mention other songs incidentally containing the word Marseillaise in their titles: La Marseillaise de 1870, La Marseillaise de la Commune, La Marseillaise des Fusillés and La Marseillaise des Travailleurs. So the Marseillaise continued to be thought of as the French and international “revolutionary anthem”. At the close of the International Socialist Workers Congress in Paris, in 1891, participants sang the Marseillaise in all languages. It was not until September 1900, in Paris, that an International Socialist Workers Congress ended with the Internationale, sung in several languages.

Routinely sung under the Paris Commune, which was as patriotic and Republican as it was revolutionary, the Marseillaise was adopted by radical Republicans opposed to the “Moral Order” governments, despite being officially banned and regarded by the government as subversive and nefarious (a confidential Ministry of the Interior circular of 10 July 1872 banned the 14 July commemorations - a “pretext for political meetings and dinners” - and reiterated the ban on the Marseillaise). But that did not stop the banned anthem from being sung at the earliest opportunity. On 28 October 1872, Louise Michel, imprisoned in Auberive (Haute-Marne) since December 1871 awaiting deportation to New Caledonia, wrote a poem entitled Anniversaire, to commemorate the anniversary of the uprising of 30 October 1870 against Bazaine’s treacherous surrender at Metz (Robert Bercy, pp. 121-122). One verse pays tribute to the Marseillaise as a song of patriotism and revolt:

When the ardent Marseillaises

Once more fill the air

Their names mingling with the storms

Shall have the fate of which we are proud

And for supreme vengeance

We must surely put

In the pillory of nations

The names of those who sold France.

It was sung, for instance, in September 1877, by the crowd following the coffin of Thiers, the “Liberator of the Territory” who had rallied to the Republic; the crowd marched in defiance of the police, who dared not intervene and risk disrupting a funeral ceremony. One more uninvited Marseillaise deserves a mention, at the national day celebrations of 30 June 1878 instituted by the government, still under the presidency of Marshal MacMahon, who had sensed the need for a national day, particularly since France was preparing to host a universal exposition in Paris that year. Monet painted the profusion of tricolour flags which, on the government’s initiative, decorated the Paris streets of Rue Montorgueil and Rue Saint-Denis that day. For the occasion, a large orchestra and choirs were to perform a new anthem, presented as the future French national anthem and entitled Vive la France (with music by Charles Gounod and words by the patriotic poet Paul Déroulède). After listening in silence to the proposed new anthem, without once applauding, the crowd called for the Marseillaise. The interior minister, who was present, agreed, and the orchestra and choirs performed it there and then, without having rehearsed, and the sizeable crowd joined in the singing in one voice. The flag and Marseillaise were to be found in a number of towns and cities that day, in addition to Republican busts being unveiled in certain town halls and squares.

V- The Marseillaise, national anthem… of the Republicans

Once the Republic was finally in the hands of the Republicans, after MacMahon stood down in late January 1879, a law was passed on 14 February 1879 declaring the Marseillaise the national anthem, this time for good. The law simply stated that the decree of 26 Messidor Year III (14 July 1795) remained in force: for the Republicans, as opportunistic as they were radical, it was a way of associating themselves with the French Revolution, to declare themselves sons of the Revolution. In the chamber, the monarchist opposition had fought a rearguard action, denouncing in vain the anthem’s association with the Reign of Terror of 1793 and the Commune of 1871, yet without offering any alternative. But then, they could hardly suggest bringing back the Restoration’s Vive Henri IV!

Making the Marseillaise the official national anthem had slightly paradoxical consequences. It gave this revolutionary anthem - or, at least, song of democratic opposition - a role of official representation which was, at the very least, incongruous with it. The inevitable result would be the creation of new songs of opposition to the established regime and the “bourgeois Republic”.

It was only natural, then, in late 19th-century France, when the Marseillaise became the official anthem of a moderate Republic, for rival songs to spring up to its left. The Carmagnole and Ça ira were taken up by the workers’ movement of the 1880s, in addition to Marianne in 1886 and, not long afterwards, the Internationale.

The Marseillaise took on increasingly patriotic overtones after Germany’s annexation of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871, and it is a peasant girl from Lorraine who, in a piece sung by popular diva Mademoiselle Amiati in 1882, refuses to give her milk to the son of a German, keeping it for her own boys, who “later on shall sing the Marseillaise”. In 1873 or 74, Amiati had given the first performance of Paul Déroulède’s Le Clairon, her greatest stage success, and had a revanchist repertoire which included Gaston Villemer and Lucien Delormel.

At the same time, though for different reasons, the monarchist right had difficulty accepting the Marseillaise. Since 1879, when it became the national anthem and therefore had to be played at certain official ceremonies, it had caused a stir, particularly in the army, where one officer banned his soldiers from playing it, while another made a show of whistling it, saying that it was “a political song” and should therefore be banned in the barracks. These officers were punished by the minister. Some prelates also showed reservations. For instance, in 1880, the new archbishop of Avignon refused the official honours to which he was entitled for his investiture: the Concordat of 1801, still in force, provided for a military band to salute the prelate with the national anthem at the ceremony. The archbishop preferred to assume his functions with no official ceremony, so as “not to be subjected to a piece of music so irksome to [his] ears”.

On 12 November 1890, at the request of Pope Leo XIII, Cardinal Lavigerie, archbishop of Algiers and founder of the White Fathers, pronounced the famous “Toast of Algiers” before French naval officers of the Mediterranean Squadron and other dignitaries. The toast, calling on them to accept the Republic, caused scandal on the right and among royalists, not least because it was followed by a performance of the Marseillaise by the Algiers seminary band. They were willing to accept the Republic, but not the Marseillaise, which “is the Revolution”! Virulent articles against the Cardinal and the “revolutionary” pope were circulated and, before long, large numbers of Catholics were rejecting the encyclical of February 1892, Au milieu des sollicitudes, calling on Catholics to accept the new French regime.

However, when, on 7 July 1887, crowds tried to prevent the “Good General Boulanger” from departing for Clermont-Ferrand, without hesitation they broke into the Marseillaise in one voice. The complexity of a national anthem rejected by part of the population, the so-called “internal émigrés” (in a reference to the aristocrats who fled France to escape the Revolution).

Meanwhile, the long tradition of songs based on the model and tone of the Marseillaise continued, with what were often subverted versions of the Marseillaise.

Here is the Marseillaise anticléricale, from 1881, ascribed to the polemicist Léo Taxil:

Take up arms, citizens

Against the clerics

Let us vote, let us vote

And may our voices

Disperse the crows!

In 1888, it was the turn of the Marseillaise de Boulanger, by Gaston Villemer. A fervent supporter of Gambetta who had converted to nationalism, Villemer wrote hundreds of patriotic songs, including the famous march Vous n’aurez pas l’Alsace et la Lorraine (You shan’t have Alsace and Lorraine). His Marseillaise de Boulanger was too anti-parliamentarian to be considered republican, at a time when supporters of General Boulanger were being recruited in their droves from the anti-republican right.

There followed, on the populist far right and at the height of the Dreyfus affair, in 1898, the Marseillaise antijuive, signed “Plume au Vent” and published in Oran by Agence Antijuive. The illustrated front cover of the score showed two women: a Marianne in Phrygian cap brandishing the tricolour flag, with the Eiffel Tower in the background; and an “Algeria” against a background of palm trees, holding a bloody sword in one hand and the severed head of a Jew in the other, and saying to Marianne, “Follow my example!” The song, a real incitement to murder, was dedicated “to Drumont, Déroulède, Rochefort [an anti-Bonapartist turned Communard, who then became a nationalist], Jumet and the Anti-Jewish French of France and Algeria”. Upon arrival in Algeria in April 1898, Drumont was received by a frenzied crowd singing this Marseillaise antijuive, before being triumphantly elected member of parliament for Algiers in May. One couplet of the song ends “Let us drive from the country / This bunch of Youddis!”, while another begins “Tremble Youpins, traitors all!”, in a rewording of the fourth verse of the Marseillaise (“Tremble tyrants, traitors all”) that maintains its vehemence while altering its target.

There were also other controversial or parodied versions of the Marseillaise , mostly at the two ends of the spectrum. On the left were Clovis Hugues’s Marseillaise Fourmisienne, also known as the Marseillaise du Premier Mai (about the workers’ demonstration in Fourmies, Nord, on 1 May 1891, which ended in massacre), the Marseillaise des Viticulteurs (Winegrowers’ Marseillaise), written in the early 20th century by the Languedocian Auguste Rouquet, and the Marseillaise de la Paix (Marseillaise of Peace), written in 1893 by Paul Robin, an unconventional libertarian teacher, who had his pacifist version sung by the children of the orphanage he ran in Cempuis (Oise), before being dismissed, partly for that reason:

(Chorus) No more arms, citizens!

Break your ranks!

Sing, let us sing!

And may peace

Fertilize our fields!

The first lines of the following chorus were similarly forceful:

No more rifles, no more cartridges,

Evil, destructive instruments...

This song enjoyed a degree of success among pacifist primary school teachers, admittedly a minority. In the Yonne, the movement was strong, thanks to the actions of history teacher Gustave Hervé, an anti-militarist socialist activist opposed to Jean Jaurès, with his “Hervéist” ideas, his article signed “a man with no homeland”, which suggested putting “the flag on the dung heap” and brought his teaching career to an end, his Affiche Rouge, and his violent pieces in the Travailleur Socialiste de l’Yonne, La Guerre Sociale (which became La Victoire) and his episodic newspaper Le Pioupiou de l'Yonne, aimed at future conscripts due to go before the recruiting board. In 1912, a scandal of national proportions was triggered when a primary school teacher called Rousseau had his pupils sing the Marseillaise de la Paix for prize-giving at Flogny-La Chapelle, Gustave Hervé. Itinéraire d'un provocateur. De l’antipatriotisme au pétainisme, Paris, La Découverte, ‘L’espace de l’histoire’ collection, 1997 and Plutôt l’insurrection que la guerre : l’antimilitarisme dans l’Yonne avant 1914, minutes of the conference of October 2006 of ADIAMOS-89, published in 2007 by ADIAMOS-89, ed. Michel Cordillot).

Within the far-left workers’ movement, there were frequent, lasting and growing misgivings about the Marseillaise as the official anthem, so that alternatives soon appeared, set either to the same tune (such as La Marseillaise de la crosse en l’air) or to different ones, in particular the various versions of Marianne, then the Internationale, which struck a chord with revolutionary and workers’ movements across the globe. L’Internationale was written in September 1870 (the exact date remains unclear; some sources say it was spring 1871) by Parisian poet and craftsman Eugène Pottier (1816-1887). A precocious poet and Bohemian literary autodidact who frequented the cabarets, Pottier had written his first song in 1830, entitled Vive la Liberté; in 1848, he wrote Les Arbres de la Liberté and in 1852 his Te Deum du Coup d’État, a virulent, parodied attack on the Prince-President. A non-commissioned officer in the Siege of Paris, then elected a member of the Commune, for which he was sentenced to death in absentia, Pottier fled to London. Upon his return to France after the amnesty law of July 1880 was passed, his poems praised the Commune, the Communards’ Wall, Auguste Blanqui, Jules Vallès and Édouard Vaillant. He struggled to make a living as a textiles worker but, shortly before his death, his poem L’Internationale was rediscovered, in 1887, by a member of Jules Guesde’s Workers’ Party. In June 1888, Guesde had it set to music by Pierre De Geyter, a Belgian-born pattern-maker in the factories of Fives, near Lille, and leader of a workers’ brass band. The Internationale was sung in public for the first time in Lille in July 1888. Pottier had died on 6 November the previous year (in May 1908, a tomb was erected in his memory at Père Lachaise cemetery, near the Communards’ Wall). The Internationale was immediately adopted as the anthem of Jules Guesde’s party (which became the French Workers’ Party at its conference in 1893). It was sung once again in July 1889 in Paris, to mark the founding of the Second International. The French Section of the Workers’ International, right from its founding in 1906, made the Internationale its anthem. It was adopted, in turn, as the official anthem of the Second International in 1910. From that time forth, translated into every language, it really became worthy of its name. It, too, had a number of variants based on it, according to the context of the moment, for instance La Grève Générale (The General Strike), in 1901, by former Communard Georges Debock, to the tune of the Internationale: “To finally bring down / The exploiting tyrants / The general strike / Will make us triumphant.”

In her thesis on the workers’ strikes of 1880 to 1890, Michelle Perrot points out that, of the 164 demonstrations she looked at, the Marseillaise was sung at 64 and the Carmagnole at 30, which shows how, for the time being at least, the songs of the French Revolution, and the subversive, oppositional nature of the Marseillaise, remained in vogue. It is true that, at the early Labour Day rallies, at the beginning of the 1890s, there were scarcely any alternatives to the Marseillaise which were known to everyone, so that the Marseillaise went on being sung, alongside other songs expressing specific demands, such as the trois-huit (division of the working day into three eight-hour periods of work, leisure and sleep). Then along came the Internationale and for a long time it supplanted the Marseillaise as the revolutionary anthem within the French workers’ movement, while outside France the two songs often continued to be associated. Similarly, for a long time, the female symbol of the Republic - admittedly dressed from head to toe in red - remained present at the workers’ marches, alongside the image of the worker with raised fist or brandishing a tool.

At the other end of the political spectrum, the national anthem was also sung, and not only by the nationalists. When, in 1902, in response to the drastic measures imposed on religious schools by prime minister Émile Combes, members of the religious congregations either closed or walked out of their establishments, crowds of supporters sang protest songs, frequently accompanied by the Marseillaise as a song of freedom; in this case, the freedom to teach, for these victims of “Masonic persecution”. Those who challenged the established order gladly displayed the official national emblems - anthem and flag - as a reminder to the forces of law and order that they, too, were an integral part of the country.

Shortly before he died, Rouget de Lisle is reported to have repeatedly said, in spring 1836: “I have made the world sing.”

We shall now go back in time, to follow the Marseillaise on its journey overseas.

American anti-war demonstrators hostile to the second invasion of Iraq sang it in California, in a nod to the efforts of President Jacques Chirac and his prime minister to avert the conflict.

It was sung in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, in 1989, by opponents of the regime, in both French and Chinese, before an impressive replica of the Statue of Liberty.

In the People’s Republic of China, the Marseillaise has always had the status of a “socialist anthem” or “patriotic song” which children are taught at school, in Chinese rather than French. Frédéric Dufourg, a literature teacher and author of a book on the Marseillaise for school children, tells how, in 1988, the only European staying at a simple hotel in rural China, he was obliged to sing the tune of the anthem in order to tell people his nationality, and not only did his Chinese listeners immediately recognise him as French, moreover they stood to attention and joined in the singing, complete with the words. The Marseillaise is also found in patriotic Chinese films about the Long March of 1949, with the character of Mao rallying his troops by having them sing it, in Chinese. Here is the Marseillaise playing its role the other side of the world!

(You can hear it sung with gusto at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S2MX9CPaMCQ&sns=em, or : https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=IbeVCRXBZNk, or :http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x8v12g_la-marseillaise-en-chinois_music, or :https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=_dchWfh_vC0)

In April 1931, in Madrid, at the official ceremony to install the Spanish Republic, the Marseillaise, regarded as a universal song of freedom, was played before the Himno de Riego, which had been adopted once again as the national anthem of a newly Republican Spain.

Also in the 1930s, the Socialist Party of Chile, which would later have Salvador Allende as its leader, took the music of the French anthem as the setting to its own Spanish lyrics. In Peru, a short time before, the ascendant Peruvian leftist party, the APRA (American Popular Revolutionary Alliance), had done the same, and seized power in Lima in August 1930 with a popular uprising to the sound of a Peruvian Marseillaise, or rather a revolutionary song to the tune of the Marseillaise. And the uprising had begun with a French film about the French Revolution, screened at a big cinema in Lima, at which the president was booed.

With the accession to power of a more moderate Popular Alliance party, with the election of Alan García, president until June 2011, the Marseillaise once again enjoyed a special status in Peru, for the duration of García’s presidency.

To celebrate the Allied victory in 1918, Uruguay gave one of the streets of its capital the name Marseillaise. And the Union Jeanne d’Arc, a “society of French and Uruguayan ladies”, founded in 1910, did a lot of good work in aid of the French soldiers during the war: charitable collections, fundraising fetes, knitting afternoons, etc. The illustrated postcard printed and sold for “French Day in Uruguay”, 14 July 1916, combines Joan of Arc on horseback, Rude’s La Marseillaise and a Marianne in Phrygian cap. Decades later, in the 1970s, a cross of Lorraine was erected in Uruguay as a memorial to another French icon: “Charles de Gaulle, citizen of the world.”

In April 1917, the Marseillaise was sung in St Petersburg to welcome Lenin, returning from exile in Switzerland in a sealed train. In February 1917, demonstrators had sung it during the first Russian Revolution - the social democratic one - and, for a period after October 1917, the Marseillaise, in Russian, was the official anthem of Soviet Russia.

Similarly, in 1905, it was a Russian Marseillaise that was sung in Odessa by the mutinying crew of the battleship Potemkin. At that time, Tsarist Russia was an ally of Republican France, When the national anthems of the two countries were played, for official state visits to either country, the musicians of the Republican or Imperial Guard would play the Marseillaise intentionally slower, abandoning its lively pace and “moustaches”, to give it the majestic rhythm of an oratorio: a formal mark of respect for an ally who must under no circumstances be perturbed! That’s the trouble with being both a national anthem and a revolutionary song, known and feared by absolute monarchies and other authoritarian regimes. Similarly, a sketch by humorist Henriot, published in Le Charivari magazine of 23 September 1896, showed President Félix Faure advising Marianne, as she made herself up, in preparation for Tsar Nicholas II’s visit to Paris: “Not too much rouge, my dear girl!”

The revolutionary uses of the Marseillaise in the 19th century were still less frequent.

On 3 August 1892, former Scottish miner and socialist leader Keir Hardie, one of the founding fathers of the British Labour Party, was elected to the House of Commons. He entered with his cap firmly on his head. On the horse-drawn carriage that took him to Parliament, a cornetist played the Marseillaise, which was standard practice at the time, in the absence of consensus over an English workers’ anthem. Throughout the 19th century, it was again the Marseillaise that was commonly sung by various radical reformist movements, with English words to fit the circumstances.

When, in November 1889, Brazilian soldiers and civilians deposed and drove Emperor Pedro II from Rio de Janeiro to proclaim a Republic, it was the Marseillaise that was sung in the main square. When the Prussians, after defeating the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, played the Marseillaise before the defeated French soldiers and civilians on the fifes of their regimental bands, it had a quite different intention: mockery. A thoroughly humiliating spectacle!

The People’s Spring of 1848 took place across Europe to the sound of the Marseillaise: in Hungarian in Budapest, in German in Vienna and Berlin, in Italian in Rome, in Polish in Warsaw, and in French in Paris.

The liberal revolutions of 1830 were also accompanied by the Marseillaise: in October 1830, when Brussels rose up against the Dutch monarch imposed on the Belgians by the 1815 Congress of Vienna; and in 1831, when Warsaw rose up against the Tsar of Russia, only to be promptly crushed. Earlier on, crowds in Paris had sung “Poles, take up arms!” to the tune of the Marseillaise.

In December 1825, in St Petersburg, liberal nobles sang the Marseillaise, in their attempt to impose a constitution on the new tsar, Nicholas I, in what became known as the Decembrist Revolt, which failed. In the 1820s, in Greece, it was a Greek Marseillaise that was sung by those rising up against the Ottomans.

Finally, it was of course sung in the revolutionary period, and we have seen how many different versions were made, in so many languages! Legend has it that the French and inhabitants of Mexico City sang it in 1794, showing that the “contagion” had very quickly spread across the ocean.

So the Marseillaise is far more than just a French anthem: it was sung across Europe, often in their own languages, by citizens fighting for freedom, independence and political or social change, throughout the 19th and early 20th century.

Once it had been adopted as the French national anthem, in February 1879, its revolutionary character as an ode to liberty became far more marked abroad than in France itself.

VII- The Great War, between Marseillaise and Madelon

The Marseillaise disguised soldiers’ fears and contributed to boosting troop morale. Its figurative representation, generally based on Rude’s relief, is found in numerous press illustrations, posters, stamps and postcards: a winged female figure leading the troops to victory, with soldiers of the Revolution standing alongside the poilus (as the French soldiers of WWI were nicknamed). She was a “substitute Marianne”, especially since both were creations of the French Revolution, and both the left and the moderate right were willing interpreters of the Great War, which began as a repeat of Valmy (against the Prussians), Jemmapes and other battles fought by the “soldiers of Year II”, a war of volunteers, citizens and beggars (Victor Hugo), who rushed to defend the “motherland in danger” (11 July 1792), to defend the land of freedom against cruelty and tyranny. The enemy in the Great War was the same as the Prussian of the wars of the Revolution, the First Empire and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, who took Alsace and Lorraine, lands of the Marseillaise and Joan of Arc.

Go, be on your way ! My breast is French!

Do not come under my roof! Take your child away!

My boys shall sing the Marseillaise

I shan’t sell my milk to the son of a German! (Le fils de l’Allemand, staged at L’Eldorado, Paris, in 1882.

In Frédéric Robert, La Marseillaise, Paris, 1989.)

Blaise Cendras, a Swiss who volunteered right from day three of the war, told how, on his first Christmas in the trenches - in Champagne, where he was to lose an arm - his company set up an old gramophone to play the Marseillaise, at the same moment as, fifty yards away, the Germans began singing O Tannenbaum: a sacred and secular national anthem versus a German popular song, charged with religiosity for some. With the union sacrée (“sacred union”; the pledge of political unity on the home front), the Internationale was briefly abandoned and, on 3 August 1914, the socialist and anarchist newspaper Le Bonnet Rouge published a note entitled “The Marseillaise replaces the Internationale”, which stated: “It is time to move on! Socialists, my brothers, let us banish our Internationale and our red flag. From now on, our anthem shall be the Marseillaise and our flag, the tricolour. Just as in 1793, the two carry the soul of the free peoples - one in its folds, the other in its verses.” The memory of the “soldiers of Year II” helped rally the left to the “sacred union” and the Marseillaise. The formerly pacifist and anti-militarist poet Gaston Montéhus (author of La Butte Rouge, La Rouge Églantine and the famous Gloire au 17e, which celebrated the soldiers’ refusal to quell the Languedoc winegrowers’ revolt of 1907) adopted the same strategy, declaring in his Lettre d’un socialo:

Let it be known that in the furnace

We shall sing the Marseillaise,

For in these terrible days,

We shall leave the Internationale

For the final victory.

We shall sing it upon our return!

This was the period in which France needed defending against “the cowardly aggressor”, and “Civilisation” and “Rights” had to be protected from “Barbarism”. But, in 1917, mutinies broke out, and the mutineers, tired of this interminable war, never once sang the Marseillaise, instead singing the Internationale, the Carmagnole or Gloire au 17e, against a backdrop of red flags, and so actively preserving the memory of the symbols of social struggle of fin-de-siècle and belle époque France.

After the war, Montéhus, the self-styled “people’s songsmith”, returned to the workers’ struggle for his inspiration, with Le Cri d’un damné de la terre or Le Cri d’un gréviste, in 1936. However, his period of “fanatical patriotism” during the Great War had lost him some admirers, not least Lenin, who would go and listen him when he was in Paris in 1909-1910.

In addition, dozens of songs were written during the war which took the tune of the Marseillaise as a setting for other words, for or against the war, patriotic or otherwise.

The Marseillaise itself was sung, as were occasional songs set to its melody, and others containing references to its lyrics, like Théodore Botrel’s Rosalie (the nickname given by the poilus to the French bayonet, praised almost as highly as the 75mm field gun), which was a parodied blend of drinking song and Marseillaise, with verses of doggerel:

Rosalie pins them to the plain

They’ve already had it in the groin

Pour us a drink!

Soon they’ll be getting it in the back

So let us drink!

Be fearless and without reproach

And may the tainted blood of the Boche

Pour us a drink!

Soak our furrows still

So let us drink!

Long a committed patriot, Edmond Rostand (of Cyrano de Bergerac fame) wrote a series of odes to the Marseillaise, up until his death in 1918, which associated the “soldier of Year II” with the poilu. In 1923, the poems were gathered together in a single volume entitled Vol de la Marseillaise (Flight of the Marseillaise). The work contributes little to literature, but it helped sustain troop morale.

Examples of patriotic postcards printed during the First World War

The anthem was a common presence on medals, posters and postcards, in the “brainwashing” propaganda that sustained morale both at the front and in the civilian zone.