Charlotte Schenique

A student of Lorraine University, Charlotte Schénique is interested in the history and heritage of the Franco-Prussian War in the region. She also works at the Musée de la Guerre de 1870 et de l’Annexion, in Gravelotte.

Why did the period immediately following the Franco-Prussian War see the advent of the first remembrance sites?

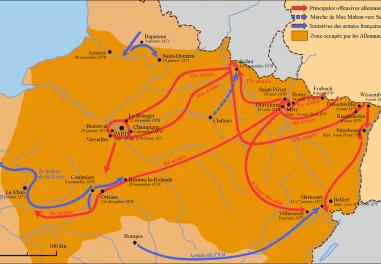

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 was already modern in terms of hardware. It caused death on a massive scale. The harsh reality of the battlefields prompted the planning of decent burial sites for the soldiers killed in the fighting. Temporary graves were dug, some of them on private property, forcing civilians to give up their land in exchange for compensation. Soldiers now received individual recognition, entitling them to a permanent place of rest. The German law of 2 February 1872 permitted the construction of war memorials in the annexed territories of Alsace-Lorraine. Meanwhile, the French law of 4 April 1873 concerned the preservation of the graves of soldiers killed in the conflict. The State could take over the ownership of land adjoining communal cemeteries, used as burial sites.

Did the erection of these war memorials raise awareness about the consequences of war?

Geographically, people became aware of these remembrance landscapes that were being constructed, and were compared to vast cemeteries. Wartime remembrance really entered the realm of everyday life. The erection of war memorials also fuelled the fragmentation of remembrance, with France’s loss of Alsace and part of Lorraine under the Treaty of Frankfurt: French remembrance centred on the cult of the dead and the great symbols of the Third Republic, while German remembrance focused on the cult of its military leaders and spread a message about maintaining the unity of the new German empire. These monuments also laid the foundations for the commemorations that would become further institutionalised after the First World War.

Can there be said to be “remembrance tourism” concerned with the Franco-Prussian War today?

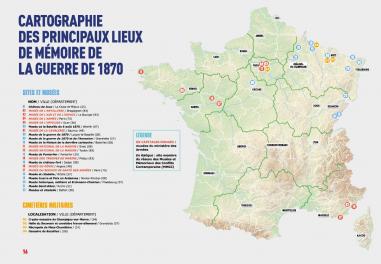

Visits to the border or the annexed territories see “pilgrims” come from across France and Germany to the battlefields around Metz. These sites have become key landmarks of remembrance tourism. The hotels in the villages get booked up and open-air conferences are held near the memorials. Twenty-five thousand people took part in the 25th anniversary commemorations of the battles around Metz. Today, we speak more of the “rediscovery” of Franco-Prussian War remembrance. Unlike the First World War remembrance sites, which are larger and more visible in the landscape, those of the Franco-Prussian War consist of more localised heritage. On this 150th anniversary of the conflict, people are rediscovering these sites and the museums that are partly devoted to them.

Are these places of contemplation at the heart of the 150th anniversary commemorations?

That is one of the key points. In Moselle and Meurthe-et-Moselle, a number of nearby villages (such as Gravelotte and Mars-la-Tour) are working together to promote the sites for a ceremony. In Gravelotte, the Musée de la Guerre de 1870 et de l’Annexion is focusing its attention on 15 and 16 August, with historical re-enactments on its battlefields. In Forbach, in the east of Moselle, a Franco-German working group is planning commemorations for 6 August at the Hauteurs de Spicheren site. The aim is to raise awareness that the Franco-Prussian War is still deeply ingrained in the landscape. These stone sentinels were symbolic sites in the formation of the respective identities of the French and German people, and remain a means of channelling wartime remembrance to call for unity and peace between the two countries.

Read more

www.cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr/ fr/les-paysages-memoriels-de-laguerre-de-1870

Articles of the review

-

The file

Understanding the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War is a forgotten war. The central place now afforded it in the première course syllabus (students aged 16 and 17) and the commemoration of its 150th anniversary in 2020 present an opportunity to remember the importance of its lessons, in particular to the understanding of the c...Read more -

The event

150 years ago: the Franco-Prussian War

Read more -

The figure

Le Souvenir Français

Founded in 1887, Le Souvenir Français is a “child” of the Republic. It was founded in response to the Republican government’s desire to use the memory of the Franco-Prussian War to “build a nation”. An heir to that conflict, it has always played an active role in its remembrance.

Read more