Le Fort de Queuleu

Following on from their Eastern European remembrance trip, the students from Metz visited the former internment and transit camp at Queuleu. It was an opportunity for them to see where European history meets the history of their region and of the Resistance fighters who were arrested there.

Built between 1868 and 1870 as part of the first chain of fortifications around Metz, the Fort de Queuleu was used by the Gestapo as an internment and transit camp during the Second World War. We went there in April. Our guide was a member of the Fort de Metz-Queuleu Association for the Remembrance of Internees-Deportees and the Protection of the Site. She began by telling us that, in 1943 and 1944, between 1500 and 1800 prisoners were interrogated and interned here before being sent to concentration camps, ‘re-education’ camps or prisons. Among them were Resistance fighters, saboteurs, smugglers, hostages, those dodging the compulsory labour camps in Germany, and Russian prisoners.

In June 1941, the “Mario” resistance group was set up in Moselle, an area annexed by Germany. Founded by Jean Burger and with around three thousand members, it became a threat to the Nazis in the region when, in 1943, it began carrying out acts of sabotage and stealing weapons. Arrested resistance fighters were held in the Fort de Queuleu, guarded by twenty or so Hitler Youth.

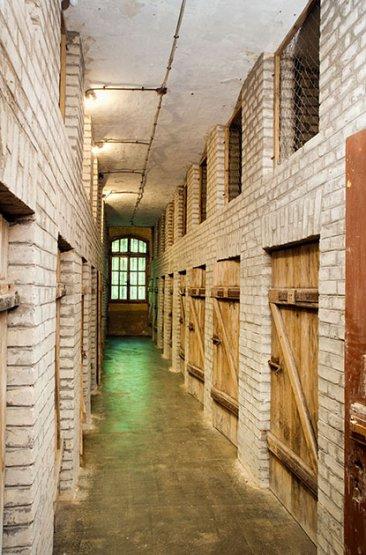

We began our tour by climbing down the main stairs, which we did with our eyes wide open, unlike the prisoners, who were blindfolded. We came to a cold, dark corridor, which led to a room recreating the prisoners’ arrival, with plastic mannequins in period dress, arms raised and eyes blindfolded. Any who did not hold their stance were beaten by the SS. Next, they were interrogated in a small room by the Gestapo. Those who talked, giving information about their group and comrades, were deemed to be of no more use and sent straight to a concentration camp; those who refused were tortured until they confessed. A heavy atmosphere pervaded the visit.

Next came the reconstructed office of Georg Hempem, the SS officer who ran the camp, then the 18 individual cells for Resistance leaders, and the group cells that would have been crammed with prisoners. Conditions were inhuman: prisoners were kept blindfolded all day, with their hands and feet bound, and were fed only soup or coffee, which was distributed in a dozen bowls, so that only those nearest the door were able to lap it up. Before the cell of Jean Burger, leader of the “Mario” group, we tried to picture him, pacing up and down to prevent himself from descending into madness.

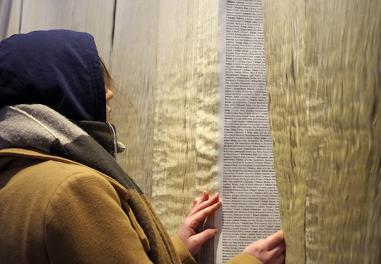

Upon arrival at the camp, detainees were deprived of their identity and received a number, which they had to recognise when it was called out in German. Octave Lang, a primary school teacher from Saint-Avold who was arrested in October 1943, recalls: “One by one, we were thrown into a kind of office, in which a Gestapo officer asked each of us our occupation. ‘Well, now, a primary school teacher... Let’s show him the SS’s teaching methods!’ Then, turning to me, he cried: ‘And remember: you’re not Monsieur Lang anymore; from now on, you’re number 124!’” The camp was evacuated in August 1944 and the prisoners were sent to concentration camps.

A short distance from our homes, this site echoed what we had seen in Poland a few weeks earlier. The realities of repression and deportation are many. They are found in different places, in Europe and at the heart of our city.

Articles of the review

-

The file

Young reporters of remembrance

Henri Borlant was the only Jewish child under 16 who was arrested in 1942 to escape from Auschwitz. Deported in July, he survived three years in the death camp. On his return, he became a doctor. When Les Chemins de la Mémoire invited him to meet with students of the Metz Lycée de la Commu...Read more -

The event

In the footsteps of la deportation

Read more -

The interview

Denis Peschanski

Head of research at the CNRS and a specialist in Second World War history and remembrance, Denis Peschanski spoke at a conference at Metz high school on the mechanisms for the construction of collective memory.

Read more