From camps without memory to remembrance without camps

There is nothing ludicrous or misplaced about referring to the internment camps as ‘landscapes’. Between 1939 and 1946, as many as 200 camps were set up, and it had a lot to do with their environment. But can one speak of ‘traces’ in the landscape outside that period?

Internment in France during the Second World War was a major phenomenon, with 600 000 people being imprisoned not for any crime they had committed, but for the potential danger they represented to the State. This was therefore an administrative process, rather than the usual procedure involving police and courts. This is not without significance to the question, insofar as the measure - and hence the buildings themselves - was invariably improvised and the authorities were convinced it would not be for long. The memory in some sense bears witness to this dual singularity.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF IMPROVISATION

There is nothing more temporary than camps of canvas tents. And such were the first camps for Spanish refugees and International Brigade volunteers, who crossed the Le Perthus pass in February 1939. On the beaches of Roussillon, at Argelès and Saint-Cyprien, most slept on the ground to begin with. To give an idea of the scale of the phenomenon, more than 450 000 people crossed the border to escape Franco’s troops, and over 100 000 were forced to sleep on the sand. By definition, no trace remains other than in photographs, nor is any trace left of the more solid temporary structures that quickly followed. It was the Spaniards themselves who were made to build these huts. They barely survived the floods of autumn 1940.

Improvisation was still the order of the day when it came to building the large-scale camps, once it was realised that they would not be returning so soon. Let us take the case of Gurs (Pyrénées-Atlantiques), built under the aegis of the highways authority. The construction of 428 huts, 382 of them for the refugees, took no more than 42 days. Work began on 15 March 1939 and was finished by 25 April, providing accommodation for up to 18 000 people. Here again, one can only imagine the impact it had on the local landscape. The capacity of the Gurs camp made it the third largest town in the department.

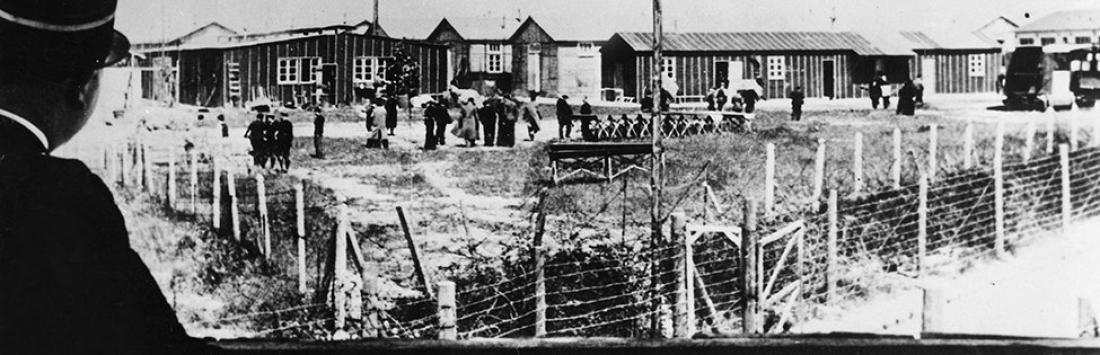

Internment camp for foreign and French Jews, built in 1941, in Drancy (Seine-Saint-Denis).

Photograph taken by the Germans in December 1942. © Roger-Viollet

Yet improvisation was also used in other, better-known, more permanent camps, like the one at Drancy. Like many others, Drancy was not a purpose-built camp, but used an existing building with a different purpose. In this eastern suburb of Paris, two well-known architects had begun, in the interwar years, the construction of a residential complex of high- and low-rise buildings to house the burgeoning population of the suburbs in very crude conditions. Strongly influenced by the American model, the architects wanted to build skyscrapers à la française - but in the middle of nowhere, and for the poor. So construction got underway on what were known at the time as Habitations Bon Marché (‘cheap housing’ - HBM, later renamed HLM). The impact on this semi-rural, semi-urban landscape was undeniable. But when war broke out, against the backdrop of the 1930s recession, construction was not finished, so the buildings were used to house a camp - to begin with, for French prisoners of war, then for nationals of countries that were enemies of the Reich, and ultimately for Jews, for which it is best known. Thousands of Jews were interned there from August 1941 onwards, before the camp became the transit centre for the deportation of Jews from France. It is not difficult to imagine the impact that this camp, which alone sent more than 65 000 Jews to the concentration camps, mostly to Auschwitz-Birkenau, had on the local landscape.

However, more commonly the sites maintained their existing function, as in the case of the Pithiviers camp, in Loiret, where the Jews rounded up in May 1941 were interned, then, after the period of deportations, political suspects, mostly communists. Here, the buildings of an existing camp for prisoners of war were used, which stood in stark contrast to its predominantly rural surroundings.

“ONLY FOR A SHORT TIME”

In all cases, the supposedly temporary nature of the camps had an impact on the kinds of traces left in the landscape. Let us return to the Gurs camp. When it was built, in the spring of 1939, the authorities intended it as a rapid stage before the refugees were either repatriated to Spain or integrated in the free labour market. A single tarmacked road in an area well-known for its autumn rains? It was of little consequence, since the camp was only meant to exist for a few months. Ill-lit huts with wooden planks for windows, which were raised in the morning and closed again at night. As long as the weather was fine, what was the problem? The problem arose when autumn came and the camp was still there. The internees then had to choose between living in the half-light (these very long huts were lit by only two or three bulbs) or opening the windows and putting up with the cold and the rain. Admittedly, over time improvements were made, but the camp, which was supposed to close in summer 1939, remained in operation until 31 December... 1945!

Commemorative stele in the cemetery for German Jewish deportees of the Second World War, Gurs (Pyrénées-Atlantiques), July 1972.

© M-A. Lapadu / Roger-Viollet

It is an extreme case, but it provides a good illustration of what the whole internment system was like: whether purpose-built or repurposed, the camps were only meant to be used for a short period. It didn’t matter what materials were used for the huts or what people thought about using social housing, barracks, disused prisons or camps for prisoners of war for this purpose, because it would only be for a short time. It was soon realised that they would be there for longer than originally planned, but it would still be a limited time.

So it could be said that the camps did have a significant impact on the local landscape, but that all the conditions were met for that impact not to extend beyond wartime and its exceptional circumstances.

This was the case of Vove, in Eure-et-Loir, where a tour of inspection in December 1941 foresaw the opening of a vast camp for political prisoners, for which the Ministry of the Interior was seeking a site in the northern zone. This camp was far from improvised. There were a number of arguments in support of such a choice: the figure of a right-wing mayor with the resources to supply the camp; an existing camp built in 1918 with huts of brick and timber, converted in 1939 for the air force then anti-aircraft defence, and used in 1940-41 to house French prisoners of war; and a perfect exterior fence consisting of 12 rows of bramble bushes three metres high and four deep, reinforced on the inside with spiral wire. It took on its new role in 1942, and the landscape of the area was completely transformed as a result. Yet although it was not improvised, this camp was not intended to be a long-term fixture.

Indeed, very few camps were intended to be for the long term. In many respects, this was the case of the Rivesaltes camp in Pyrénées-Orientales. The construction of a military facility - a kind of huge garrison - had long been planned for this area of approximately 600 hectares. With the war, the decision was made to turn it into a permanent camp. Permanent is not really the word, given how fragile the huts were. But on 14 January 1941, the camp began receiving Jews, Spaniards and gypsies, often families; then, between August and November 1942, it served as a transit camp for Jews handed over to the Germans by Vichy, first for the region, then for the entire southern zone. When the Germans invaded the southern zone in November 1942, they decided to turn it into a garrison. With the German defeat, the site was used as an internment camp for suspected collaborators, before becoming an important camp for German prisoners of war. It then reverted to its military function, being used by the army for its own troops and, between 1962 and 1964, to garrison 22 000 harkis, auxiliaries to the French army in Algeria. It is no coincidence, then, that in these groups of half-demolished huts, in the midst of which stands a memorial unveiled in 2015, traces of internment can still be seen, or one at least has an awareness, simply from the presence of the site in the landscape, with no need to be familiar with its history, of what that internment might have been like.

The former Rivesaltes camp. © K. Dolmaire

REMEMBRANCE HAS COME TOO LATE

The case of Rivesaltes raises the question of remembrance. We know the extent to which the remaining installations at Buchenwald, Mauthausen and Auschwitz have marked the landscape, so that they are at the heart of the development of European remembrance. The same can hardly be said of France, despite the fact that, as we have seen, internment was a mass phenomenon which went on for years at local and even regional level. So what happened? One phrase sums it up: we have gone from camps without memory to remembrance without camps.

After the Second World War, with a few exceptions, the French internment camps were not remembrance sites. Most had already been abandoned and the huts, often crude constructions, as we have seen, demolished. More importantly, however, the camps did not have a place in the collective memory, or where they did, for example the camp at Châteaubriant, the constructions were too crude to last.

In most cases, after they had been used for the internment of suspected collaborators or black marketeers, or for holding prisoners of war, the camps were demolished, as at Beaune-la-Rolande and Gurs, or else reverted to their original purpose. For example, a social-housing complex was indeed completed at Drancy (before the skyscrapers were demolished); the citadel of Sisteron was returned to the prison service; the Milles tile factory, near Aix, reverted to its industrial purpose.

By the time the names of the camps had found a place in the collective memory, or had at least become a part of the lively remembrance debate, it was generally too late for any significant traces to be found in the local landscape. In the late 1970s, when a number of studies were carried out on these camps, the sites were indeed still there, but they were now mostly no more than a name, the buildings having all but disappeared from the landscape. Thus, the time has come for a negotiation between the widely shared desire for remembrance and an acknowledgement of the ravages of time. The landscape of internment has become, for the most part, a representation.

Denis Peschanski - Head of research at the CNRS, chairman of the scientific committee of the Caen Memorial and Rivesaltes Camp Memorial, and a member of the scientific committee of ECPAD.

Related articles

- L'internement : La France des camps (1938-1946)

- L'internement des tsiganes en France 1940-1946

- The internment of the Gypsies in France during the Second World War

- Camp d'Internement pour les Tsiganes, Montreuil-Bellay (49)

- Les autres lieux d'internement en Ariège (09)

- Les camps dans le Gers (32)

- Les camps dans les Pyrénées-Atlantiques (64)

- Les camps d'internement dans les Hautes-Pyrénées (65)

- Camps dans les Pyrénées-orientales (66)

- Les autres camps dans le Tarn-et-Garonne (82)