The French illustrated press during the First World War

The French illustrated press played a particular role in the representation of World War I since it was the only medium which depicted what our contemporaries refer to as the ”reality” of war.

The French illustrated press played a particular role in the representation of World War I since it was the only medium which depicted what our contemporaries refer to as the ”reality” of war.

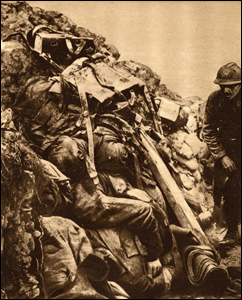

Extremely violent photographs

Three main themes conjured up most specifically the violence of war: devastated landscapes, battles and dead bodies. The images of no man's land in turmoil were able, more effectively than fields of ruins, to rouse the idea of the chaos that resulted from industrial warfare.

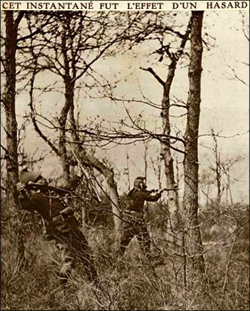

Le Miroir presented a vision that changed according to the chronology of the battles: forests of mutilated trunks and no men in Verdun, human dumping grounds in the Somme. Clearly the images would never have shown readers actual hand-to-hand fighting. Nevertheless, using small, easily-portable cameras and celluloid, photographers—who were sometimes able to take the lens as far as the battlefield and who were also known to make reconstructions—managed to render tangible the dangers of modern battle, composed of smoke and projections with bodies bent over or even hit on occasion.

Pourquoi cette spécificité française ?

This gallery of the photographic horrors of war only existed in France. We might wonder why France was such a special case. There are two main reasons.

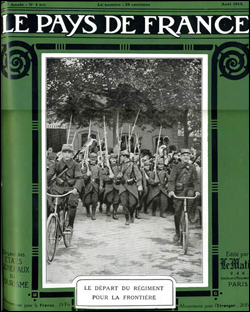

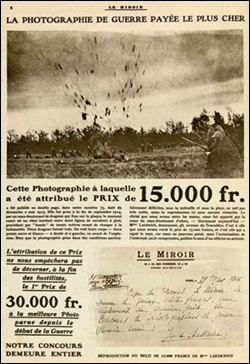

The first reason was the call made out to photography enthusiasts, who were encouraged by photography competitions. Le Miroir launched a call for amateur photographers on 6 August 1914. Hot on its heels, L'Illustration printed a callout for any interesting photos on 15 August 1914. Following a lack of convincing results, on 14 March 1915 Le Miroir launched its contest to find ”the most striking photograph of the war” for a ”prize” of 30,000 francs. This excessive initiative provoked shockwaves in the illustrated press: on 15 April 1915, Le Pays de France started a weekly competition offering a first prize of 250 francs; on 16 May 1915, Le Miroir responded by introducing a monthly contest with prizes of 250, 500 and 1,000 francs; on 19 June 1915, Le Flambeau offered a weekly first prize of 250 francs. The mounting number of competitions spurred soldiers on to find a scoop. Amateur photographers became ”fighting photographers”.

The second reason was the attitude towards censorship, which neither prohibited nor commented on the images of violence. This can be explained firstly by the fact that opinions were only given on the final proofs of magazine, just a matter of days before their publication. Not to mention that weeklies did not always respect the injunctions placed on them. Thirdly, contrary to Germany and the US, the censors balked at sanctioning any breaches of regulations and lacked effective means to mount pressure on a magazine press that was often resistant to their decisions. However, some events indicate that the censors could strike hard, like when it seized an issue of L'Illustration showing Russian deserters in 1917. It rather seems that the realistic depiction of the horrors of war scarcely bothered the authorities at all. Lastly, France was an invaded, assaulted and mutilated nation: it was represented as it lived.

A visual culture vs. ”brainwashing”

It is therefore difficult to support the idea of ”brainwashing” through images in France between 1914 and 1918. Even the hackneyed news gathered during the first few months of conflict, before the contests in 1915, suggest a deficit of documentation and a reluctant visual culture, rather than a desire to mask the extreme violence of the war. Later, even when the photographs depicted the everyday life of soldiers on the front, they abandoned the heroic and derisive tone of the military epic in favour of a transformation of masculinity, where the soldier is an ”everyday hero”, steeped in suffering and abnegation.

French illustrated magazines opened the way for new journalistic practices in war correspondence and, in doing so, confronted the public with the vilest displays of warfare.

Joëlle Beurier. Professor of History, associate researcher at the CRESC (Centre for Research on Spaces, Societies and Culture).

Bibliography

Thilo Eisermann, Pressephotographie und Informationskontrolle im Ersten Weltkrieg. Deutschland und Frankreich im Vergleich, Ingrid Kämpfer Verlag, Hamburg, 2000.

Joëlle Beurier, Images et violence. Quand Le Miroir racontait la Grande Guerre…, Paris, Nouveau Monde, 2007.

Joëlle Beurier, Photographier la Grande Guerre, France-Allemagne, Rennes, PUR, 2012 (coming soon).

Website : L'Illustration

Le Pays de France, août 1914. Libre de droit.

La piste du fort et l'église de Douaumont. Le Miroir, date inconnue. Libre de droit.

Cet instantané fut l'effet d'un hasard. Le Miroir, 9 mai 1915.

Devant Malancourt pendant la bataille . Le Miroir, 25 juin 1916. Libre de droit.

Après un assaut L'Illustration. Date inconnue. Libre de droit.

Concours photographique de "la plus saisissante photographie de la guerre". Le Miroir. Date inconnue. Libre de droit.