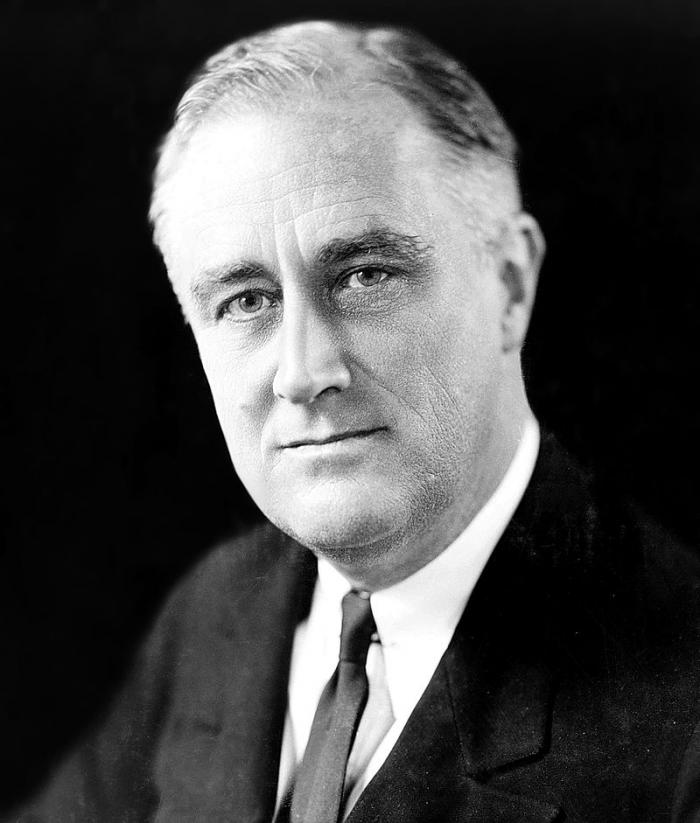

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Born on 30 January 1882, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was the descendent of a Dutch colonial family that immigrated to the United States in the 17th century. A graduate of the prestigious Harvard University, he undertook a career as an attorney before going into politics in the footsteps of his cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States from 1901 to 1909.

A rising star in the Democratic Party, his career began in 1910 when he was elected to the New York State Senate. In 1913, he was appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy by President Woodrow Wilson. During World War I, he worked in favour of the development of submarines and supported the project for installing the North Sea Mine Barrage to protect Allied ships from attacks by German submarines.

He met Winston Churchill for the first time during an inspection tour in Great Britain and on the French front.

Put in charge of demobilization after the Armistice, he left his job at the Navy in July 1920. That same year, the Democrats’ defeat in the Presidential election issued in a long period in the political wilderness during which he contracted a disease that caused him to lose the use of his legs in 1921.

He returned to the political scene in 1928, when he was elected Governor of New York State. During his term, he undertook reforms in favour of rural areas and in social policy, notably setting up the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration to help the unemployed, reducing working hours for women and children and overseeing improvements to hospitals. He also exercised tolerance in terms of immigration and religion. His action was successful and was validated by his re-election in 1930.

In 1932, Roosevelt was nominated as the Democratic Party’s candidate for the Presidential election, basing his campaign on the New Deal, an economic recovery programme designed to put an end to the crisis that hit the country with the stock market crash of 1929. Elected with 57% of the votes, he implemented his economic recovery programme and fought against unemployment, reformed the American banking system and founded Social Security. While still fragile, the economy progressively recovered and Roosevelt was re-elected in 1936 and again in 1940.

As the situation deteriorated in Europe, he sought to break with the United States’ policy of isolationism and neutrality supported by the American Congress and public opinion. He first obtained the repeal of laws on the embargo on arms sales to the warring parties in September 1937 and then, in 1941, received authorisation from Congress for arms assistance to the Allies, without reimbursement. The Lend-Lease law, signed on 11 March 1941, enabled the Americans to supply the Allies with war materiel without intervening in the conflict directly. On 14 August 1941, Roosevelt and Churchill signed the Atlantic Charter, a joint declaration defining the moral principles that were to inspire the establishment of a lasting peace and which was later to serve as the basis for the United Nations’ Charter (June 1945).

In the meantime, in the Pacific, relations between Japan and the Western Powers were deteriorating. The United States gave their support to China, opposed to Japan, by granting lend-lease and then, when Japan refused to withdraw from Indochina and China, the United States, Great Britain and the Netherlands decided on an embargo over raw materials, while Japan’s assets in the United States were frozen. On 7 December 1941, Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbor, the largest American naval base in the Pacific Ocean, bringing the United States into the war.

In 1942, Roosevelt gave priority to the European front while containing the Japanese advances in the Pacific. The United States thus intervened alongside the British, first in North Africa (Operation Torch in November 1942), and then in Europe with landings in Italy and France.

During the conflict, he was one of the main players in the inter-ally conferences (Anfa in January 1943 for the choice of the next front in Europe and Germany’s unconditional surrender, Dumbarton Oaks in August-October 1944 to prepare the constituent meeting for the United Nations, Yalta in February 1945 to solve the problems of post-war Europe).

Roosevelt did not recognise General de Gaulle’s legitimacy and was wary of him because he saw him as an apprentice dictator. He was opposed to letting Free France take part in the United Nations so long as elections had not been held in France. Laval’s return to power in 1942 led the United States to recall its ambassador from Vichy and to open a consulate in Brazzaville. The American President successively supported Admiral Darlan – a notorious collaborator – then General Giraud – a clear Vichy loyalist – and tried to block the action of the Comité Français de la Libération Nationale (French Committee of National Liberation) in Algiers, the leadership of which de Gaulle had firmly taken, relegating Giraud to strictly military tasks.

His idea of placing liberated France under American military occupation (AMGOT) never happened, as General Eisenhower had reassured de Gaulle, on 30 December 1943, “I will recognize no French power in France other than your own in the practical sphere.” As a gesture of appeasement and to satisfy the American press and public opinion that were very favourable to the General, he welcomed him to Washington in July 1944. But he did not officially recognise the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPFR - Gouvernement Provisoire de la République Française) until October of 1944 and did not invite its head to Yalta in a sign that his mistrust was not totally assuaged.

On 7 November 1944, Franklin Roosevelt was re-elected to a fourth term in the White House. He died suddenly of a cerebral haemorrhage on 12 April 1945. In application of the American constitution, Vice-President Harry Truman succeeded him.