“Arise, children of the motherland”

Sous-titre

The people and the Marseillaise

By Laurent Martino

PhD in History from the University of Lorraine

History and Geography Teacher, Académie de Nancy-Metz

The first verse of the Marseillaise addresses the people. By the people, we mean the French as a Nation. How have the “children of the motherland” used La Marseillaise? How have the people taken over this revolutionary song turned national anthem? They have loved it and at times criticised it. They have appropriated it throughout its history. The people of France have adapted it to suit the moment, making it an ode to Liberty, Equality, Fraternity and the Republic, and finding in it the values and symbols it needed. The Marseillaise has become a mirror of history, a source by which to understand the evolution of society. Each version, each interpretation tells us something about that period. This article does not aspire to be exhaustive; instead, we will look at a small number of significant examples.

At the height of the Revolution, the Battle Song of the Army of the Rhine

When Claude Rouget de Lisle wrote the Marseillaise in Strasbourg on the night of 25 to 26 April 1792, the National Assembly had just declared war on Austria, on 20 April. It was therefore a battle song as much as a patriotic song. The song begins with the phrase “Arise, children of the motherland”, which refers to the volunteers who have joined up. For the revolutionaries, the call to citizens to volunteer was necessary in order to drive back the enemy from their frontiers. For the first time, the army was not an army run by nobles; it was an egalitarian, people’s army.

From Strasbourg, the song reached the south of France. François Mireur, a representative of the Society of Friends of the Constitution, who had come to the south to coordinate the departures of volunteers to the front, sang it at a banquet in Marseille[1]. In view of its success, he had it published and the federate troops from Marseille adopted it as their marching song. They disseminated it on their march across the country. They sang it on their triumphant entrance to the Tuileries, in Paris, on 30 July 1792. As it was sung by federate troops from Marseille, the Parisian crowds, unconcerned about its different names, immediately christened it L’hymne des Marseillais, or ‘The anthem of the Marseille folk’. Through simplification, it quickly became La Marseillaise Besides its simplicity, this name had the advantage of stressing the unity of the Nation, from Strasbourg to Marseille, the East to the South of France.

Score of the Marseillaise. Engraving of the words and music of the Marseillaise,

by William Holland, done at 50 Oxford Street, London, on 10 November 1792.

During the French Revolution, civic festivals developed as a means of ensuring the cohesion of the population around new values. The French Revolution brought music to the streets. Music left the enclosed spaces and became one of the tools for rallying the people around the revolutionary ideology. The open-air festivities were an opportunity for the organisers to make a display of national unity[2]. The model was the Fête de la Fédération, or ‘Festival of the Federation’. On 14 July 1790, in Paris, representatives of the National Guard from across the country paraded around the Champ de Mars. A mass was held and a sermon of national unity was given. Bernard Sarrette, the great organiser of the revolutionary festivals, had well understood, as he wrote in Le Journal de Paris of 22 November 1793, that there was “no Republic without national festivals, and no national festivals without music”. At these occasions, the Marseillaise was played in order to introduce it to the population and, in so doing, to propagate the ideas of the new regime: Liberty, Equality, the fight against absolutism. It had seven couplets which developed these new values.

These events - almost celebrations - needed musicians. The use of wind instruments can be explained by two reasons, one functional, one acoustic. They enabled the music to be heard by a crowd, because brasses produce a much louder sound than many instruments. Wind ensembles also constituted a social alternative to the elitist instrumental custom of the Ancien Régime, in which strings and harpsichords had pride of place. They expressed fully the ambition of a music for the people, by the people. Yet the revolutionary festivals were characterised by order, organisation and a military aspect. They were not at all spontaneous, and the people themselves ultimately made very little contribution. Instead, they were spectators. Contrary to the image of a period of major renewal that symbolises the Revolution, the festivals remained imbued with the religious model, the processional form simply having lost its sacred aura. They also borrowed much from traditional formal ceremonies. As Mona Ozouf puts it: “It is this amalgam that should be seen as the real novelty of the [Fête de la] Fédération. By no means the invention of a previously unheard-of ceremonial form, but a fusion of disparate elements. A verbal and visual syncretism[3]. »

Open-air performances, not only of the Marseillaise but also Chant du départ (words by Chénier and music by Méhul) and L’hymne à la Liberté (words by Rouget de Lisle and music by I. Pleyel), with large numbers of instrumentalists and singers, had a powerful impact on audiences. With the staging of these spectacles, the regime hoped to reinforce the ideas of the Revolution, using both the words and the music of the song as a propaganda instrument. They also hoped the crowds would join in the singing and therefore be rallied to the cause. This mass of sound should contribute to their enthusiasm. The Marseillaise brought the people together to sing in one voice, the voice of the French Nation. The power of the words centres on the simplicity of the vocabulary which is, and is intended to be, comprehensible to all, “and on the powerful rhythmic element produced by the conjunction of the music and the text[4]. » Of course, the singing masses may not have understood every word, but they were accustomed to singing hymns in Latin and therefore were content to make do with a sense of the overall meaning, rather than a word-for-word understanding[5].

This has a lot to do with the structure of the Marseillaise, both its melody and its poetic composition. Musically, after a thunderous start comes a more subtle melody, with a warlike refrain. To Gildas Harnois, the current director of the band of the Paris police, the Musique des Gardiens de la Paix, “this combination reveals a people that has its destiny in its hands. It symbolises the spirit of the Revolution and the movements of rebellion, and even the spirit of the Resistance[6]. » The rhythm is sustained by the poetic and instructional repetitions of the text. Each of the seven couplets is followed by the same refrain. In the refrain itself, which is a rallying call, the word Marchons (literally “Let us march”, though often translated as “March on”) is repeated. Similarly, every third verse is repeated. There are certain recurring themes and keywords, for instance motherland, Liberty, blood, Fraternity, arms, war, despotism. The use of the imperative (“Arise!”, “Tremble!”, etc.), more succinct because it takes no pronoun (compare “You arise”, “You tremble”, and so on), “is an effective call to action as much because of its punchiness as the meaning it conveys. [7]» The whole song is made to rally the people.

The Marseillaise was declared a national anthem on 14 July 1795. Banned under the Empire, which preferred Veillons au salut de l’Empire (words by Adrien-Simon Boy, music by Nicolas Dalayrac), the Restoration continued to proscribe it in favour of the anthem of the French monarchy, Vive Henri IV.

In the 19th century, the performing of La Marseillaise reflects national quarrels

On 27, 28 and 29 July 1830, the people rose up against the monarchy. The soundtrack to what became known as the ‘Three Glorious Days’ was the Marseillaise, which in the early 19th century was still a symbol of struggle against absolutism and for Liberty. The Marseillaise was permitted once again in 1830, during the constitutional monarchy of Louis-Philippe, King of the French. Amid the general euphoria, Hector Berlioz, a great French composer with an interest in wind music, arranged the Marseillaise for two choirs and a large orchestra. His imposing version, powerful and energetic, was for Berlioz a tribute to the people and a personification of the masses risen in revolt. According to him, it should be sung by “all those who had a voice, a heart and blood in their veins.”

Soon rejected by the July Monarchy, the Marseillaise became anathema.

The Marseillaise is undeniably associated with wind music and brass bands because it is so often performed in the open air. The 19th century saw the birth of the orphéon movement of local music groups - originally choral societies, then wind ensembles too - formed of amateur musicians. These groups made music accessible to the common people. Guillaume-Louis Bocquillon, known as Wilhem (1781-1842), developed the practice of singing groups in the early 1820s. A group of wealthy middle-class liberals belonging to the Société pour l’Instruction Élémentaire wanted music, in particular singing, to be taught in Parisian primary schools. They assigned the task to him[8]. In 1833, Wilhem published a collection of choral music entitled Orphéon, the name he later gave to his vocal ensemble, founded in 1836. Initially formed of children, they were soon joined by adults. Starting in 1848, Eugène Delaporte (1818-1886) undertook a series of journeys all over France to promote these choral societies, henceforth known as orphéons»[9] after Orpheus, the hero of Greek mythology. The founders of the early orphéons wanted to make classical music accessible to ordinary people. They therefore had a dual aim, artistic and educational: to train musicians, and to educate the people, forming them into citizens. The orphéons gradually went from being vocal to instrumental groups. From 1850 onwards, there was rapid development of instrumental ensembles, so that, by the 1880s, they surpassed the number of choral societies.

Playing the Marseillaise meant laying claim to the spirit of the Revolution and affirming republican ideas. Under the Second Empire, the Chorale d’Annecy was regarded as having republican leanings and advocating the return of the Republic. In 1864, at a competition in Lyon, it performed a version of the Marseillaise[10].

Under the Second Empire, Napoleon III banned this anthem which “stirred up the Revolution”. In the 1870s, the Marseillaise was sung by the people during the Commune and made a lasting return to the streets and banqueting halls, a symbol of republicanism and a call for the return of Alsace-Lorraine after its annexation by the Germans.

In 1875, republican ideas began to take over the country. A majority in the municipal assemblies and the Senate from 1879, the Republic now belonged to the republicans. That same year, Jules Grévy became the first French President with republican tendencies.

In this context, the Marseillaise was of crucial importance. It became the official anthem on 14 February 1879. The Third Republic reaffirmed its claim to the heritage of the Revolution of 1789 and the First Republic. Yet because the republican Republic was installed without triumph, the Marseillaise became the French anthem almost reluctantly.

To disseminate the values of the Republic, in the 1880s the State made it compulsory for local authorities to organise and fund national day celebrations[11].

The French Revolution had made the role of instrumental ensembles indispensable to these displays of nationhood and patriotism at what were always open-air civic occasions. They were a practical means of providing loud, mobile music. The use of brass bands in the staging of the republican celebrations was far more than purely decorative. The tunes they played transmitted memories and messages, acting as a tool of republican propaganda. Music played the role of intermediary in the dissemination of republican ideas. A universal language, it spoke to everyone and touched the emotions[12]. More generally, patriotic anthems or refrains could be joined in by everyone, backed up by the instruments of the wind ensemble. They were a concrete expression of the communion of citizens. It is also interesting to note how the creation of the orphéons coincided with the idea of the nation state, as though one were reliant on the other. Anyone could join, sing the words and, in so doing, assent to the ideas conveyed by these pieces of music. Music gathered without separating. For the musicologist and composer Julien Tiersot, music is the only art form to achieve the dual goal of the national day commemorations: “It contributed to their outward glamour at the same as expressing private sentiments[13]. » Rousseau, the theoretician of the Republican City, extended his political thinking to the expressive power of music. In his Écrits sur la musique, he stresses the importance of melody over harmony for the success of festive gatherings. The melody gets into the heads of listener-spectators, who can join in to become listener-spectator-participants. Many experts still share this view. The crowd effect means that large gatherings cement relations within communities. And music groups have an important role to play in this. On 14 July 1878, the Festival National des Orphéons brought together 700 choirs and instrumental ensembles in the Tuileries Gardens, in Paris, to perform before an audience of 200 000. The event was brought to a close with a performance of the Marseillaise by all the groups together[14].

Because of the role they played in rallying the people, carrying along crowds of onlookers and leading the party, brass bands were an important element to have control over. That being the case, brass bands always accompanied the torchlit processions in towns and villages on the eve of the 14th July, designated the Fête Nationale in 1880. In the context of these civic celebrations, the brass bands contributed to politicising the crowds. They were a vehicle for educating the population and bolstering support for the regime. They played a role in the assimilation of republican ideas. The Marseillaise was played at the end of the ball or firework display, to round off the mayor’s speech. The Marseillaise sung in one voice was a moment of intense emotion[15].

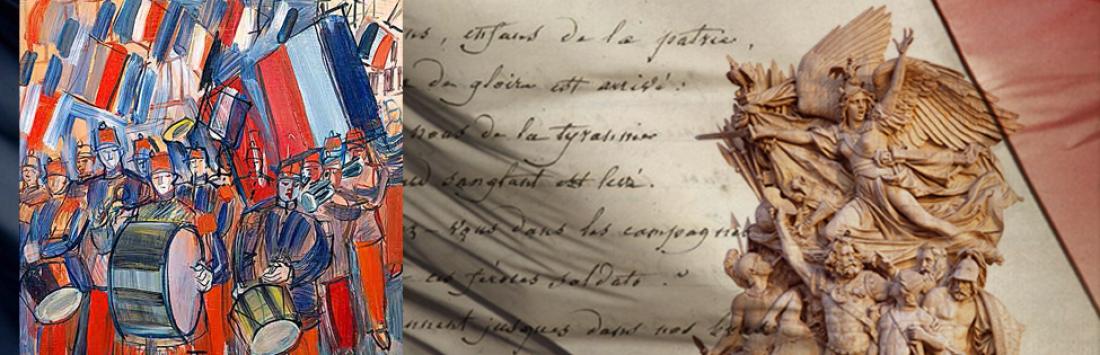

La fanfare, Raoul Dufy, oil on card, 40 x 40.5 cm, 1951

Musée d’Art Moderne André Malraux, Le Havre

The Marseillaise was at the centre of the debates of the period, namely the confrontation between monarchists and republicans and between the Church and advocates of secularism. It was not instantly accepted by everyone.

In the Vendée, a department that was majority legitimist until 1893, the issue of support for the republican regime crystallised around symbols as much as values. The Marseillaise was too much associated with the Revolution and, for supporters of the monarchy, to hear it evoked bad memories. In receipt of financial support from the regional authorities since 1873, in 1878 the Société Philharmonique de la Roche-sur-Yon had that support cut, along with the orphéons of Fontenay-le-Comte, Les Sables-d’Olonne, Luçon and Île-d’Elle. To justify the decision, the department’s elected representatives referred to the inclusion of the Marseillaise in their repertoire - a revolutionary anthem, as Monsieur Bourgeois declared in 1879:

“For as long as this song recalls not only our soldiers marching towards the enemy, but also the bloody deaths of innocents murdered in the Revolution, I shall not vote for a single cent to go to music groups which perform the song. […] I can only applaud the fact that the Marseillaise was sung at the frontier; but there are colleagues here whose parents were guillotined to the sound of the Marseillaise. Why not cast aside these gloomy memories? Are there not enough seeds of discord amongst us, in our beloved Vendée, and is it not high time we abandoned all of these acts which have the effect of widening the existing divide between our citizens? The Marseillaise sung ostentatiously is a provocation, which is why we felt it our duty to protest on behalf of our constituents.” [16]

Similarly, by choosing to participate in the republican commemorations, musical societies were regarded by monarchists as showing their support for the republican regime. In 1884, the Société Philharmonique de Luçon paid the price of the politico-religious tensions which shook the Vendée. It was refused the annual funding of 250 francs[17]which it had hitherto received from the Vendée authorities, on the grounds that it had “included the Marseillaise in its repertoire”[18]. On the other hand, members who refused to take part in an official ceremony where they would have to play the Marseillaise were seen as adopting an anti-republican stance.

As in the political sphere, musical societies were split along secular and religious lines, which sometimes intersected republican-monarchist divisions. As a result, musical societies found themselves in a position where they had to pick a side. The clerics criticised the Marseillaise for containing no allusions to God, unlike many other national anthems, such as The Star-Spangled Banner of the United States. The monarchists saw it only as the revolutionary song that had prompted the slaughter of the nobility.

For the orphéons, this schism manifested itself in name changes, splits and/or the founding of new musical societies. More often than not, musical societies found themselves caught up in the game of political manipulation conducted by the politico-religious authorities of the commune. Both a political instrument and a tool for entry into politics, brass bands were also divided by conflict between the mayor and the parish priest over the sharing of public space and the organisation of festivals. Occasionally, these conflicts of power or influence would lead to internal discord, mostly as a result of some players refusing to perform at a particular event. Such disputes would call into question who was the higher authority, the mayor or the priest, and could lead to confrontations between rival societies. In 1882, the brass band of Charquemont, in the Doubs, split into two rival societies, after the local priest banned the Marseillaise from being performed. The schism, along politico-religious lines, resulted in the formation of the Catholic La Philharmonique and the republican La Démocrate, pitting the sacred music of Les Blancs (the Catholics) against the secular music of Les Rouges (the anticlericals)[19].

Singing and playing the Marseillaise was no trivial matter. In the 19th century, it meant adopting a pro-Republic, anti-monarchy, anti-clergy stance. To sing it or play it was to educate the people and canvas support for the Republic, which was increasingly strong.

The First World War: La Marseillaise, between triumph and a bitter aftertaste

Throughout the period of German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine (1871-1919), for the local population singing or playing the Marseillaise meant continuing o assert their French identity. Any occasion was treated as an opportunity to reaffirm their ties with France. The unveiling of the French war memorial in Wissembourg, on 17 October 1909, was marked by a Francophile - not to say pro-French - demonstration masterminded by Auguste Spinner[20] and Le Souvenir Français. 50 000 to 100 000 people gathered that day to remember the French soldiers who died in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). After Spinner’s speech, the memorial was unveiled and the many bands present performed the Marseillaise. The public in turn sang the words of the French anthem before the dumbfounded German authorities.

On 31 August 1914, the German Empire announced a “state of danger of war”. Immediately, the border was closed and the next day, French troops were mobilised. Contrary to popular imagery, there were few scenes of enthusiasm; instead, the mood was reserved. The Marseillaise may have been sung here or there, as the population bid farewell to its soldiers and saluted those on their way to the front. With the mobilisation of summer 1914 came the consecration of the French national anthem. Made official only 30 years previously, in 1879, it now became the genuine people’s anthem. Accounts of scenes of departure vary little, and all of them stress the omnipresence of the Marseillaise. This Marseillaise expressed the “sacred union” (the pledge of political unity on the home front) and the people rallying to defend a Republic and a Nation in danger.

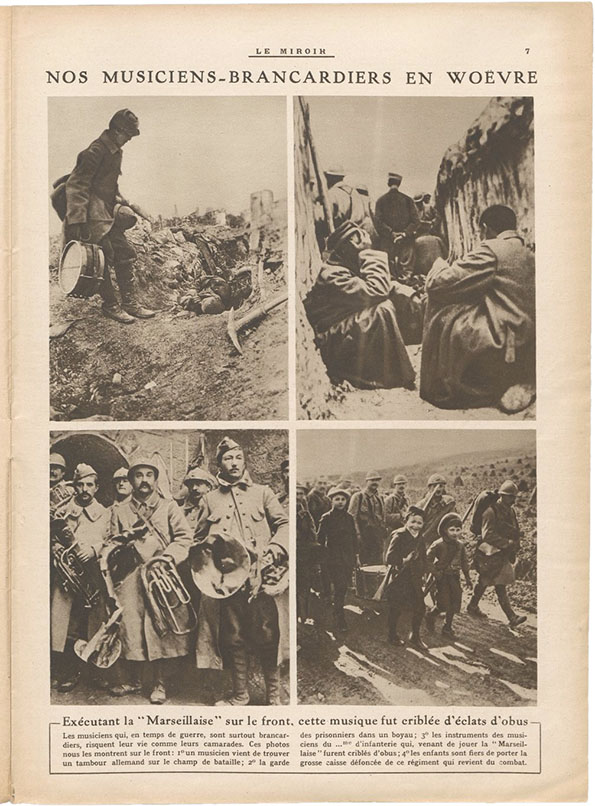

In the early days of the war, the troops arrived at the front in serried ranks, the music fresh in their minds. It was an unchanging ritual: the musicians played the Marseillaise and the soldiers emerged from the trenches to fight the enemy. This Marseillaise fired up the troops. It regained its warlike undertones of 1792. The musicians also acted as stretcher-bearers, but continued to bolster the troops’ morale through music. Some paid with their lives[21]. Military bands also gave concerts in the civilian zone to raise money for the troops and the civilian population. Without fail, they would end with the Marseillaise[22], in a moment of communion between the population and their army.

Extract from the magazine Le Miroir Illustré, 23 April 1916

Throughout the conflict, the Marseillaise was ever-present to rally a warring France around the patriotic values it conveys, and also its history. French President Raymond Poincaré even decided to transfer Rouget de Lisle’s ashes to Les Invalides. The ceremony took place on 14 July 1915[23]. It honoured the composer of a fighting anthem, which galvanised men’s energies and made them march. In his speech, Poincaré described the Marseillaise as “a cry of vengeance and indignation from a people who, for the past 125 years, has no longer bowed before foreigners”, and he recalled that the Marseillaise was an “affirmation of French unity”.

As the conflict went on, the Marseillaise reached saturation, both at the front and in the civilian zone. The Marseillaise had become jaded. It became associated with the slaughter in the trenches and the elites who masterminded it, and some rejected it.

When the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine became French once more, the population greeted the authorities to the sound of the Marseillaise. On 10 December 1918, president Poincaré and prime minister Georges Clemenceau arrived at Mulhouse railway station at 1.30 pm[24]. Crowds lined the pavements, as 2 000 school children sang the Marseillaise, as a symbol of the restored Republic. The fact that they were children singing it further reinforced the symbolism, because they were born Germans and at the same time embodied the country’s future. Several days’ rehearsals were required, for many of the children were not familiar with the Marseillaise and had never sung it at the tops of their voices before, in public.

Once the war was over, the veterans gathered around the war memorials for ceremonies that were neither official, nor military, but funerary[25]. The Marseillaise had trouble finding its place. For a long time there was hesitation and, although the anthem was often sung at the end of ceremonies, it was not compulsory. Not all villages had a brass band to play it, so it had to be sung by either the church or the school choir. There may have been misgivings about an anthem which came across as bellicose and triumphant being sung at funerary ceremonies, and occasionally funeral marches or hymns were preferred.

Gradually, a protocol was established. A much-needed new bugle call, entitled Sonnerie aux Morts in dedication to the dead, was composed in 1931 by Pierre Dupond, musical director of the Republican Guard band. On the score, Commander Dupond noted that it had become a legal requirement in 1932. It was performed each evening at the flame ceremony before the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, and at any ceremony or occasion held in remembrance of the soldiers killed on the battlefield. The bugle call was followed by a minute’s silence, rounded off with a rousing Marseillaise: France’s homage to its fallen soldiers. The cult of the dead was therefore an opportunity for a lesson in civicism, in a fixed, unchanging ritual setting: gathering around a war memorial, minute’s silence, laying of wreaths, bugle call. At these occasions, performances of the Marseillaise by military and brass bands were sometimes unpredictable. To introduce some order, the Rabaud Commission, instituted following intervention from the education and war ministries, commissioned Dupond to produce an official arrangement of the national anthem. In 1938, he presented a new transcription, which conformed strictly to the version established by the official commission of 1887, chaired by Ambroise Thomas. That is the version which remains in use to this day.

Resistants, collaborators, Vichyists: all wanted their own Marseillaise

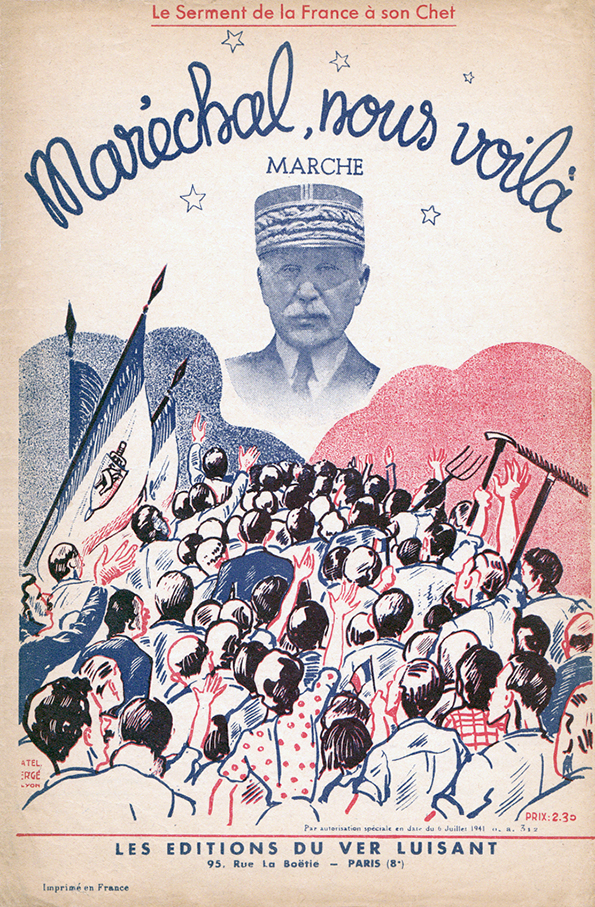

In the Second World War, the Marseillaise was outlawed from 17 July 1941 in the zone occupied by the Nazis. It was banned to prevent it from taking on rebellious overtones and out of a desire to strip France of its national symbols and sovereignty[26]. In the northern zone, the issue was more ambiguous. The Vichy regime kept the Marseillaise as its anthem but, alongside it, Maréchal nous voilà, written by André Montagard and Charles Courtioux in 1941, acquired near-anthem status. It was sung at public events and achieved popular success. For Nathalie Dompnier, that success can be explained by its vigorous rhythm, in vogue for songs of the time, its military-sporting style and the fact that it was sung by the stars of popular music, in particular Andrex[27]. It was sung by school children and used frequently by the regime in its propaganda. The Marseillaise therefore did not disappear, but it was often shortened, to preserve only the verses best suited to the regime of the French State and the circumstances of occupation. The preferred couplets were The preferred couplets were Allons enfants de la patrie… (“Arise, children of the motherland...”), Amour sacré de la Patrie… (“Sacred love of the Motherland...”) and, occasionally, Nous entrerons dans la carrière…(“Into the fight we too shall enter...”). The sixth couplet was commonly referred to as “the Marshal’s couplet” or “the Marshal’s favourite couplet”.

Front cover of the score to Maréchal nous voilà,

original edition

Couplet 6

Sacred love of the Motherland,

Lead and sustain our avenging arms!

Liberty, cherished Liberty,

Join the struggle with your defenders! (repeat)

Beneath our flags may victory

Rally to your manly strains!

May your expiring enemies

See you triumph and our glory!

The Marseillaise thus took on a new meaning, becoming more a song of love for the motherland than a song of war and revolution. It was not until 1941, however, that the Marseillaise became the official anthem of the French State. Admiral François Darlan, head of the Vichy government from February 1941 to April 1942, wanted to give the song back its official status and restore all the respect it deserved, in particular when it was being performed. The regime wanted to rally the population around its anthem, the values it conveyed and therefore the regime which had made it its own[28]. “Singing in groups unites participants.” The Law of June 1941 “on outward signs of respect to be shown by the civilian population at the passage of the national emblems and during the performance of the national anthem or the Sonnerie aux Morts bugle call [29]», set out the attitude to be adopted when La Marseillaise was performed: the military salute, civilians to stand motionless, men with their hats off. Its performance by civilian brass bands was permitted only in the presence of a member of the government or with special permission from the prefect. The Darlan bill made its performance illegal other than at official events, subject to fines and one to six days’ imprisonment. The two anthems coexisted, but the Marseillaise retained a more formal aspect. On Pétain’s visit to the capital in April 1944, Parisians sang the Marseillaise publicly for the first time since 1940. Similarly, on 26 May 1944, when he visited Nancy, the Place Stanislas thronged with people[30]. Around 7 pm, the crowd broke into Maréchal nous voilà, followed immediately by the Marseillaise, then Pétain addressed the city’s inhabitants.

The regime intended in this way to keep control over the Marseillaise in the ceremonial context and, more generally, over its performance in the public domain. War and propaganda were also played out around the national anthem. The Resistance certainly conducted a campaign urging the French people to take over the Marseillaise. For the Resistance, namely in the underground press, the call for the return of the Republic relied on frequently quoting the words of the revolutionary anthem. The French people were also encouraged to make those words their own and to sing them at protests against the German occupiers. The Marseillaise, a timeless song of struggle, was sung at banned demonstrations, in the prisons, in the maquis (rural guerrilla groups) and before the firing squads. It preserved its role as a patriotic anthem. At the execution of the 27 resistants of Châteaubriant, on 22 October 1941, or that of Gabriel Péri on 15 December 1941, the Marseillaise was their last utterance[31]. At Clairvaux prison in June 1942, at the execution of prisoners accused of communist resistance by the Germans, all the inmates present stood and broke into the Marseillaise as a sign of opposition[32]. At underground 11th November commemorations, the banned Marseillaise rang out across many towns and villages, in a display of provocation, passive resistance and patriotism. There are also many accounts which tell of hearing the Marseillaise whistled in the street or played on a busker’s accordion or in the Parisian nightclubs, subtly mixed in with the melodies of songs in vogue. But was it an act of resistance? It is a difficult question to answer. It can be seen as a rejection of occupation, or even an attachment to the Republic, but above all as an attachment to the national anthem, a symbol of France’s independence. At that time, the Marseillaise illustrated perfectly the situation of a population divided between waiting, resistance and collaboration. All laid claim to the Marseillaise. As a result, there was more than one Marseillaise.

Like most associations, the Harmonie de la Haute-Moselle, in Neuves Maisons, Meurthe-et-Moselle, lay dormant during the war and German occupation. However, one account recalls a concert at Pont-Saint-Vincent held in aid of French prisoners, at which the group, likely more out of habit than as an act of resistance, ended their performance with the Marseillaise. The handful of German soldiers present contented themselves with a military salute. “Fortunately, they weren’t SS,” adds the writer.

The PPF (Parti Populaire Français), the most active and organised collaborationist party during the occupation, founded and led by Jacques Doriot, also laid claim to the Marseillaise. At a meeting attended by Doriot in the Vosges, on 13 May 1942, the 800 people present in the hall enthusiastically sang the Marseillaise at the request of the prefect[33].

The Marseillaise rang out in the Nazi internment and extermination camps, an ode to Liberty, to resistance against the oppressor. Arriving in Birkenau by train, Adelaïde Hautval[34] tells how the women sang the Marseillaise as they got down from the wagons, in an act of defiance. The other deportees inside the camp regarded the event in different terms. Some thought it was a riot, while others saw it as a moment of hope and emotion.

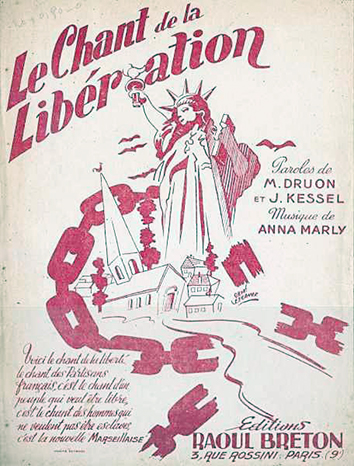

Front cover of the original score to Le Chant de la Libération, Chant des Partisans,

original edition

The ban on the Marseillaise by the Nazi authorities in the occupied zone, the ban on dances and the creation of the counter-anthem, Maréchal nous voilà, in honour of Marshal Pétain, shows how important songs and music were to propaganda. The BBC and the Resistance broadcast patriotic songs. Among them was Chant des Partisans, written in 1943 to music by Anna Marly, with words by Maurice Druon and Joseph Kessel. This song of freedom quickly became a sign of recognition among resistants. At Liberation, it was regarded almost as a national anthem, and was played at all ceremonies alongside the Marseillaise.

At Liberation, the population sang the Marseillaise in the streets and at the dances which blossomed all over the country. In 1946, Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli produced a jazz version of the French anthem; Echoes of France was recorded in London, the headquarters of General de Gaulle and the Free French Forces during the war. A symbol of liberation after German occupation and of the role played by the Americans in France, the Marseillaise was given a jazzy swing in this improvisation by the two historic members of the Quintette du Hot Club de France. But this jazz version was not well received. At that time, to play about with the national anthem was sacrilege.

On his post-Liberation tour of France, General de Gaulle sang the Marseillaise everywhere he went. He “stamped with his authority this reclaimed Marseillaise, with which he identified”[35]. » It came out of the Second World War renewed. National reconciliation and the “government of unanimity” were played out to the theme of the Marseillaise.

The second half of the 20th century: debate concealed by unanimity

After the Second World War, the Marseillaise became unquestionably France’s national anthem once again. It was enshrined in the constitutions of the Fourth and Fifth Republics, of 1946 and 1958.

In September 1944, a circular from the education ministry advocated the singing of the Marseillaise in schools to “celebrate our liberation and our martyrs”. The following year, a memo was issued by France’s provisional government to the effect that it would henceforth be compulsory for five patriotic songs to be studied in primary schools[36]. These were La Marseillaise, La Marche Lorraine, Le Chant du Départ, Le Chant des Girondins (or Le Régiment de Sambre et Meuse) and Le Chant de la Libération (also known as Le Chant des Partisans). Learnt during the course of their schooling, the songs were performed by pupils at the time of their examinations for the Certificat d’études primaires (certificate of completion of primary education). Thus, school singing was used for the purposes of civic education. After four years of occupation, France felt the need to symbolically assert its identity, unity and cohesion by reaffirming its values. This involved, in particular, performing the Marseillaise. At the same time, the State encouraged school children to take part in the commemorations and sing the Marseillaise. Such occasions were an open-air lesson in history and civic education.

The law of 23 April 2005 made it compulsory once again for the Marseillaise to be learnt at primary school.

In his book La fête républicaine, Olivier Ihl points out that there were fewer republican celebrations in 20th-century France than in the previous century. Fewer participants, less glamour and less fervour can all be explained by the fact that there was less of a need to celebrate the Republic. The Republic was no longer a battle to be won; it was now established, and events to commemorate it became commonplace, since there was no longer any need to defend it. Nevertheless, republican celebrations continued to exist, and music played an important role in them. As well as contributing to social cohesion and providing entertainment, music was also an instrument of political propaganda.

The events were made more formal by the participation of a brass band. With a brass band, the commemoration was set to music, and appropriate pieces distilled the key events in the history of the Republic. Playing La Madelon on Remembrance Day or La Marche de la 2e DB on VE Day had meaning, which was to recall the hardships of the trenches and the determination of the liberators of General Leclerc’s 2nd Armoured Division. So music conveyed memory, which complemented words and speeches.

In the 19th century, civic and political rituals were introduced, inspired in large part by religious rites. Anthems became the musical personification of the State and its values. Like all political entities, anthems were part of protocol. They were played by civilian or military bands at official ceremonies.

Every year, brass bands took part in the official commemorations. It became customary to round off their concerts with the national anthem. Similarly, visits from personalities or members of the government were an occasion for an official reception by the commune, with authorities and residents in attendance. The local musical society would rarely be left out. Its participation in the civic rite would uplift the occasion through music that was often tailored to the circumstances. Music played a ceremonial role. The performances signified a show of respect from the community to its visitors. The brass band played a crucial role in providing the setting. It enabled the community to pay its respects in the non-verbal language of music.

Alongside these official ceremonies, the Bastille Day dances were resumed in earnest after the Second World War. They were an occasion for residents to gather together, and also a republican ritual. At some point in the proceedings, the band would strike up the Marseillaise, often before the firework display, where there was one.

In a similar fashion, if to more festive effect, the presence of a brass band became de rigueur at sporting events. The band would perform at fixtures between national teams. In the context of spectator sports, the anthems were part of the almost warlike display staged between two nations. Packed stands of supporters would join in the singing. The anthems also celebrated sporting victories in major championships.

Even if the national anthem status ascribed to the Marseillaise was no longer questioned in post-war France, it nonetheless remained a source of debate.

On 6 October 2001, the Marseillaise was whistled by numbers of fans during the France-Algeria football match, after being played to open the match. This provoked a strong reaction from public opinion, and the political class seized control of the issue. On 11 May 2002, at the final of the Coupe de France between Bastia and Lorient, the Marseillaise was hissed by the Corsican supporters. French President Jacques Chirac left the stand and the stadium without awarding the trophy to the winning side. It is hard to come up with a clear and entirely satisfactory explanation. Such behaviour can be explained by a whole combination of factors, which are amplified by the crowd effect. Firstly, it reflects animosity towards the adversary, from fans who want to see their team win. It also serves as a provocation, or for some even a rejection of France, which takes the form of disrespect for a national symbol. But that rejection or provocation is not the same for a Corsican calling for the island’s independence, a young person from a deprived neighbourhood or an Algerian immigrant. Does it reflect the problems of integration faced by young people from immigrant families? Some are quick to lump them all together, in view of the residual open wound of the Algerian War, which may still be expressed in those whistles. The attempt to exploit the match for political purposes was also amplified. Announced beforehand as a symbol of political reconciliation between France and Algeria, some sought to put a damper on that rapprochement. As a consequence, a law was passed in January 2003 making it a criminal offence to desecrate the Marseillaise. Initially an individual offence, in March that year it was extended to included “public sporting, recreational or cultural demonstrations”.

Similarly, regular criticism is levelled at the words of the Marseillaise. They are regarded as warlike and violent, and some would like to see them replaced with a more peaceful message. But surveys show that the French are still strongly attached to their anthem, and no politician has dared touch the Marseillaise.

Part of the country’s historical and cultural heritage, many artists, singers and actors have recorded their own versions of the Marseillaise, or songs referencing it. They are either critiques or tributes to the anthem and what it stands for. The are the sounding board for the different visions of the Marseillaise that coexist in society. Michel Sardou, Philippe Clay, André Dassary, Lucien Lupi, Catherine Sauvage and others have included in their repertoires without touching either the lyrics or the music. More critical, Mireille Mathieu’s Pour une Marseillaise, from 1975, sought to “erase the words of a battle song to make it a song of peace”. Léo Ferré, more cutting in his La Marseillaise of 1967, denounced the massacres and bloodshed perpetrated in his name and that of nationalism, which the anthem symbolises in his eyes. In 1967, Omar Sharif recorded a 7-inch single in which, over Rouget de Lisle’s music arranged by Michel Bernholc, he proclaims his love for France and the Marseillaise, “which, to the foreigner that I am, (...) represents all that I love about this country”. More recently, in 2006, Charlélie Couture’s Ma Marseillaise offers his vision of the anthem. “The Marseillaise is a battle cry, but mine is a cry of love,” he said on France 2’s one o’clock news broadcast, on 6 November 2006. But these recordings are rarely commercial successes, with the exception of Aux armes et cætera, Serge Gainsbourg’s reggae version recorded in 1979. Everything the singer said or did after it was seen as a provocation[37]. Although he may have intended to be controversial, his Marseillaise lies somewhere between disrespect and tribute, being musically as much as politically provocative. It was above all Michel Droit’s article in Le Figaro magazine of 1 June 1979 which sparked off the controversy, describing Gainsbourg’s version as anti-Semitic, anti-patriotic and scandalous. However, the album’s commercial success - selling over 100 000 copies in the month following its release and reaching number one in the French charts - show its popular appeal and the French people’s acceptance of Gainsbourg’s appropriation of the national anthem.

Other artists have sought to be even more deliberately provocative with their versions of the Marseillaise, notably the Parisian punk rock band Oberkampf, with their deconstructed version from 1983. Inspired by Jimmy Hendrix’s anti-establishment version of The Star-Spangled Banner, the guitarist and founder of the band, Pat Kebra, decided to do the same with the French anthem[38]. It was not a political critique of France and the State, but a social protest. To attack a national anthem is to attack society. Paradoxically, they found in its lyrics an energy and a revolutionary ideal which appealed to them. They sing the actual words, only replacing the usual couplet with the so-called “children’s couplet”: “Into the fight we too shall enter, When our fathers are dead and gone” is a powerful echo of their revolt against authority and the generation of their parents. Yet given their far more limited reach than Serge Gainsbourg, their Marseillaise and their revolt went almost unnoticed, except for a brief appearance in Philippe Manœuvre’s TV programme Les Enfants du Rock, in December 1983.

Even today, people continue to make the Marseillaise their own. A quick search on YouTube throws up numerous versions of the anthem. Some sing it in the traditional way, but most give it their own interpretation, in styles that range from rock to rap to raï, and a diversity of colours that reflects today’s society.

2015 was marked by a wave of terrorist attacks without precedent in France. In Paris and throughout France, on 11 January 2015, processions in response to the jihadist attacks of 7, 8 and 9 January took place noiselessly. Only the Marseillaise interrupted the silence. Each time it was followed by applause. This was a soft, serious, solemn Marseillaise, whose words were not shouted. It was sung spontaneously, as a sign of communion and fellowship expressed by the people. Citizens took over the national anthem. The Marseillaise unified them. No longer was it controversial, but revealed a need for unity and meaning, and to reaffirm the values of the Republic. We must nevertheless sound a cautionary note: the demonstrations gathered together four million people, which is a lot, but that number is relatively small compared to the total population of France (65 million). We must be careful not to make hasty generalisations and extrapolate from what four million people expressed. Historians need to analyse the event objectively over the coming years to determine the real extent of national unity.

Following the terrorist attacks of 13 November 2015, three days of national mourning were declared. On 15 November, a service was held at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris in honour of the victims, which was attended by numerous political figures. During the offertory, organist Olivier Latry improvised a variation on the Marseillaise, in a moment of union[39]. When they recognised the tune being played, the whole congregation rose. Some even waved little tricolour flags on either side of the nave.

The Marseillaise embodies an important part of French history. To sing it is also to participate in collective battles and struggles and evoke national glories. A song of revolution and freedom, it was not always permitted by the authorities and the people at times rejected it. But ultimately it triumphed, to become the symbol and embodiment of France and its people. It has gone from being a revolutionary anthem, to a patriotic song that celebrates the motherland and national cohesion.

Having become an element of national heritage, the different interpretations, appropriations and critiques of the Marseillaise are precious indications of how French society is evolving and what its aspirations are.

[1] Frédéric Robert, La Marseillaise, Paris, Nouvelles Editions du pavillon/Imprimerie nationales, 1989, p. 25

[2] Mona Ozouf, La fête révolutionnaire, Paris, Gallimard, 1976, p. 152

[3] Mona Ozouf, La fête révolutionnaire, Paris, Gallimard, 1976, p. 66

[4] Béatrice Didier, « Stylistique des hymnes révolutionnaires », pp.109-117, in : Jean-Rémy Julien et Jean-Claude Klein, Orphée Phrygien. Les musiques de la Révolution, Vibrations, éditions du May, Paris, 1989, p. 113

[5] Béatrice Didier, « Stylistique des hymnes révolutionnaires », pp.109-117, in : Jean-Rémy Julien et Jean-Claude Klein, Orphée Phrygien. Les musiques de la Révolution, Vibrations, éditions du May, Paris, 1989, p. 117

[6] INTERVIEW : la Marseillaise vue par Gildas Harnois, chef de la Musique des gardiens de la paix,

http://prefpolice-leblog.fr/interview-la-marseillaise-vue-par-gildas-harnois-chef-de-la-musique-des-gardiens-de-la-paix , vu le 29 octobre 2016.

[7] Béatrice Didier, « Stylistique des hymnes révolutionnaires », pp.109-117, in : Jean-Rémy Julien et Jean-Claude Klein, Orphée Phrygien. Les musiques de la Révolution, Vibrations, éditions du May, Paris, 1989, p. 111

[8] Philippe Gumplowicz, Les Travaux d’Orphée. Cent cinquante ans de vie musicale en France. Harmonies, chorales, fanfares, Paris, Aubier, 1987, rééd. 2001, p. 202.

[9] Paul Gerbod, « L’institution orphéonique en France du XIXe siècle au XXe siècle. », « Ethnologie française », I, 1980, p. 28

[10] Philippe Gumplowicz Les Travaux d’Orphée. Cent cinquante ans de vie musicale en France. Harmonies, chorales, fanfares, Paris, Aubier, 1987, rééd. 2001, p. 175

[11] Jann Pasler, La République, la musique et le citoyen (1871-1914), Paris, NRF Editions Gallimard, 2015, p. 284

[12] Olivier Ihl, La fête républicaine, Paris, NRF Editions Gallimard, 1996, p. 158, 324

[13] Julien Tiersot, Les Fêtes et les chants de la Révolution française, Paris, Hachette, 1908, p. XV

[14] Olivier Ihl, La fête républicaine, Paris, NRF Editions Gallimard, 1996, p. 325-326

[15] Olivier Ihl, La fête républicaine, Paris, NRF Editions Gallimard, 1996, p. 159-160

[16] Archives Départementales de Vendée, 4 Num 220/79, 1879. Cited by Soizic Lebrat in ‘Le mouvement orphéonique en question : du national au local (Vendée 1845-1939)’, doctoral thesis in history supervised by Guy Saupin, 2012, Université de Nantes, p. 246

[17] ADV. BIB ADM PB 14. Bulletins des délibérations du conseil général de la Vendée, 1879-1887. Cited by Soizic Lebrat in ‘Le mouvement orphéonique en question : du national au local (Vendée 1845-1939)’, doctoral thesis in history supervised by Guy Saupin, 2012, Université de Nantes, pp. 386-387

[18] ADV. 4M122. Lettre du sous-préfet au préfet, 19 décembre 1884. Cited by Soizic Lebrat in ‘Le mouvement orphéonique en question : du national au local (Vendée 1845-1939)’, doctoral thesis in history supervised by Guy Saupin, 2012, Université de Nantes, pp. 386-387

[19] Petit Vincent, « Religion, fanfare et politique à Charquemont (Doubs) », Ethnologie française, 2004/4 Vol. 34, pp. 707-716, p. 708

[20] See: Philippe Tomasetti, Auguste Spinner. Un patriote alsacien au service de la France. Promoteur du monument du Geisberg à Wissembourg, Nancy, Éditions Place Stanislas, 2009, pp. 49-61

[21] Armand Raucoules, De la musique et des militaires, Paris, Somogy/Ministère de la défense, 2008, p. 33

[22] Sophie-Anne Letterier, « Les concerts au front », pp. 77-87, p. 84, in Florence Gétreau (dir.), Entendre la guerre. Sons, musiques et silences en 14-18, Paris, Gallimard/Historial de la Grande Guerre, 2014.

[23] Michel Vovelle, « La Marseillaise. La guerre ou la paix », pp. 85-136, p. 125 in Pierre Nora (dir.), Les lieux de mémoire. T1. La République, Paris, Gallimard, 1984.

[24] Philippe Husser, Journal d’un instituteur alsacien entre la France et l’Allemagne, 1914-1951, Paris, Hachette, 1989.

[25] Antoine Prost, « Les monuments aux morts. Culte républicain ? Culte civique ? Culte patriotique ? », pp. 195-225, p. 208, 210 in Pierre Nora (dir.), Les lieux de mémoire. T1. La République, Paris, Gallimard, 1984.

[26] Nathalie Dompnier, « Entre La Marseillaise et Maréchal, nous voilà ! Quel hymne pour le régime de Vichy ? », pp. 69-88, p. 70, in Myriam Chimènes (dir.), La vie musicale sous Vichy, Paris, Éditions Complexe – IRPMF-CNRS, coll. « Histoire du temps présent », 2001.

[27] Nathalie Dompnier, « Entre La Marseillaise et Maréchal, nous voilà ! Quel hymne pour le régime de Vichy ? », pp. 69-88, p. 71, 75 in Myriam Chimènes (dir.), La vie musicale sous Vichy, Éditions Complexe – IRPMF-CNRS, coll. « Histoire du temps présent », 2001.

[28] Nathalie Dompnier, « Entre La Marseillaise et Maréchal, nous voilà ! Quel hymne pour le régime de Vichy ? », pp. 69-88, p. 77-78, in Myriam Chimènes (dir.), La vie musicale sous Vichy, Éditions Complexe – IRPMF-CNRS, coll. « Histoire du temps présent », 2001.

[29] Archives Nationales F41 295, projet du 14 juin 1941.

[30] François Moulin, Lorraine années noires, de la collaboration à l'épuration, Strasbourg, La Nuée Bleue, 2009,

p. 26

[31] Frédéric Robert, La Marseillaise, Paris, Nouvelles Editions du pavillon/Imprimerie nationales, 1989, p. 135

[32] Raymond-Léopold Bruckberger, Si grande peine, chronique des années 1940-1948, Paris, Grasset, 1967, p. 103-104

[33] François Moulin, Lorraine années noires, de la collaboration à l'épuration, Strasbourg, La Nuée Bleue, 2009, p. 116

[34] Adelaïde Hautval, Médecine et crimes contre l’humanité, Paris, Actes Sud, 1991.

[35] Michel Vovelle, « La Marseillaise. La guerre ou la paix », pp. 85-136, p. 125 in Pierre Nora (dir.), Les lieux de mémoire. T1. La République, Paris, Gallimard, 1984, p. 132

[36] Michèle Alten, « Un siècle d'enseignement musical à l'école primaire », « Vingtième Siècle, revue d'histoire », 1997, Volume 55, Numéro 1, pp. 3-15, p. 6-7

[37] Francfort Didier, « La Marseillaise de Serge Gainsbourg », « Vingtième Siècle ». Revue d'histoire, 1/2007 (n° 93), pp. 27-35.

[38] Témoignage de Pat Kebra, recueilli le 26 novembre 2016.

[39] Judikael Hirel, « À Notre-Dame de Paris, l'orgue a joué La Marseillaise pour les victimes », Publié le 16/11/2015, Le Point.fr, vu le 27 novembre 2016.