Remembering the victims of terrorist attacks

France has been a regular target of terrorist attacks since the end of the Algerian War. For a long time, such attacks prompted ad hoc memorial ceremonies, mostly on the initiative of victims’ organisations. It was not until 2015 that a systematic public policy of national remembrance of the victims of terrorism was introduced.

In September 2018, the French president announced the upcoming creation of a museum and memorial to society’s fight against terrorism. And on 11 March 2020, the French State held its first National Remembrance Day for the Victims of Terrorism, taking the European Union’s lead on the date.

How to delimit the remembrance?

The choice of 11 March was, in part at least, a solution, via a European detour, to the matter of choosing between several dates on which terrorist attacks have taken place on French soil. It is a delicate business remembering the victims of a “historic” act that nevertheless goes on repeating itself on different dates. In the present case, delimiting a beginning and an end to the act of terror was impossible.

Deciding what and whom to remember was no more straightforward. Established in July 2016, the National Medal of Recognition of the Victims of Terrorism was initially intended to be awarded to the victims of acts of terrorism since 1 January 2006. Yet the list of events taken into consideration has grown substantially in length, so that the medal now concerns the period since 1 January 1974. The medal’s design, on the other hand, met with general approval from the outset. At its centre is an engraving of the statue in Paris’s Place de la République. The site of the principal spontaneous memorial in the wake of the attack of 7 January 2015, the Place de la République has become a powerful symbol.

From the ephemeral to the permanent

It was there, too, that the first permanent memorial to the series of terror attacks that began with the Charlie Hebdo massacre was unveiled. To mark the first anniversary of the January 2015 attacks, Paris city council and the French President’s office had initially planned to plant 17 trees in the square, in reference to the number of victims. Trees are an ancient symbol of resilience in Judeo-Christian culture, and had previously been used to remember the attacks in Madrid, New York and Oklahoma City.

Preparations for the tree-planting were well under way when 13 November 2015 happened. In the end, it was decided that a single tree would be planted. In January 2016, this “Remembrance Oak” was unveiled in the corner of the square, on the 10th arrondissement side, with the following inscription at its base: “In memory of the victims of the terrorist attacks of January and November 2015 in Paris, Montrouge and Saint-Denis. On this spot, the people of France pay their tribute.” This first official memorial thus remembered events, some of which were barely two months old. Here, a monument was erected when the spontaneous public demonstrations of solidarity were still taking place just a few dozen metres away, at the foot of the Marianne statue in the centre of the Place de la République. In a way, the tree’s symbolic significance never fully recovered from this initial conflict.

“Remembrance Oak” planted in January 2016 in Place de la République, Paris, in memory of the victims of the terrorist attacks of January and November 2015. © S. Gensburger

Since its planting, the tree has never really been adopted by society. It is not visited, and most users of the square, tourists and Parisians alike, are unaware of its existence.

From commemorative plaques to a museum and memorial

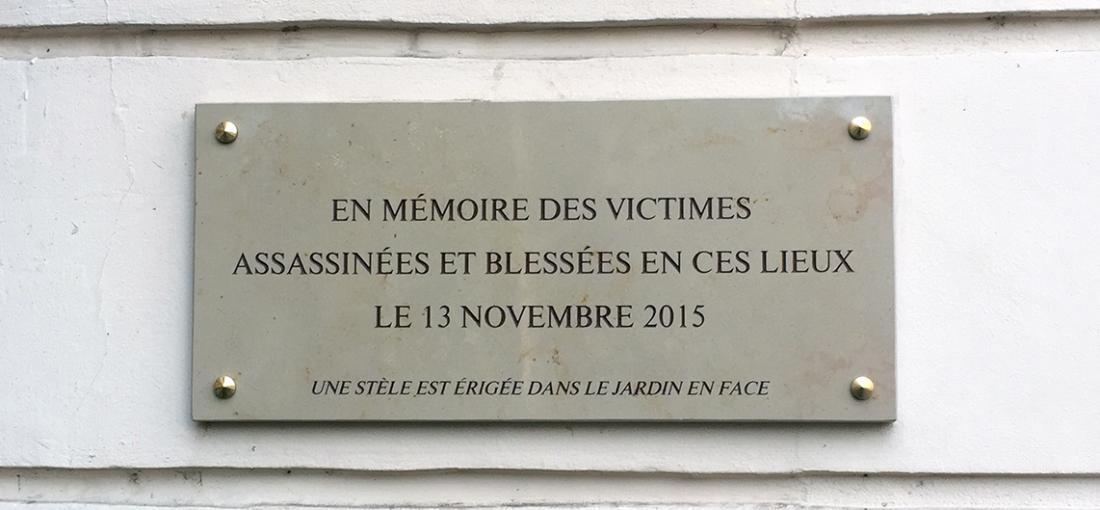

Since then, other remembrance sites in memory of the events of 2015 have been unveiled. In January and November 2016, for the first anniversary of the events, the decision was taken for the remembrance topography to be modelled on the map of the attacks. A commemorative plaque was laid at each of the sites targeted (cafés, concert venue and football stadium). Here, again, there was nothing original about the use of such plaques. And those unveiled in 2016 did not break with customary practice. They bear all the names of the victims.

However, in the 10th and 11th arrondissements, there is no plaque in memory of the November victims on the actual walls of the building where the massacre took place. They were all laid ten metres away from the site, either on public buildings or street furniture. Only the façade of the Bataclan has a small inscription, which directs the visitor to the square opposite, where the actual commemorative plaque bearing the names of the dead is located. Between forms of mourning and the desire for a return to normality, the quest for visibility and a concern for invisibility, on sites that all have an economic purpose, remembrance must find its rightful place.

Yet the difficulty in finding a single remembrance site for the attacks that hit eastern Paris in 2015 is but one illustration of the complexity of choosing a pertinent symbolic site for France to remember the victims of the terrorist attacks as diverse as those of Nice on 14 July 2016 or Strasbourg on 11 December 2018, or so many others that have followed or preceded them, including, long before the recent period, the Saint-Michel train bombing in 1995, the attack on the Tati store on Rue de Rennes in 1986, or the 1989 bombing of a DC-10 of former French airline UTA, which exploded in mid-flight, killing the crew and passengers, including several dozen French citizens. Where, then, should terrorist attacks and their victims be remembered? Answering this question was one of the main challenges faced by the preliminary planning committee of the museum and memorial, led by historian Henry Rousso (Le Musée-Mémorial des sociétés face au terrorisme, Report to the Prime Minister, 2020, available for consultation at www.vie-publique.fr). To answer it, the decision was made to take memory and society, past and future, together, to offer a plural reflection on “societies against terrorism”, recalling that remembrance should, first and foremost, be based on the writing of the account of events and the lessons to be learned from them for the future. Otherwise, they may make little sense to the group they are intended for.