1958 A new Republic at war

The year 1958 saw an exceptional situation. Profound institutional changes took place as the country remained embroiled in a war with no end in sight after four years. By passing a new constitution, General de Gaulle hoped to bring an end to the political crisis.

In 1958, the Algerian War entered its fifth year. It seemed to be at an impasse, both politically and diplomatically. Talks with the independence camp, under way since 1956, were at a standstill due to irreconcilable differences: the National Liberation Front (FLN) was calling for total independence, while France sought to maintain its sovereignty over Algeria’s three departments. So the fighting continued, in particular along the Tunisian border, where the “Battle of the Borders” got under way..

The conflict, whose cost soared, divided the country. It therefore seems legitimate to ask to what extent General de Gaulle’s return to power in May 1958, and the constitutional reform of October that year, created a new dynamic not seen since the start of the Algerian War, which offered hope of a solution to the crisis. Militarily, the French Army succeeded in regaining the initiative, while politically, General de Gaulle inspired confidence in his intention to put an end to the conflict, the new constitution of October 1958 offering a number of possible solutions.

Towards a weakening of the National Liberation Army

Since 1955, the FLN had been working to establish an army that might alleviate the admittedly limited pressure exerted by the arrival of the French contingent. An organisational effort was made at the Soummam Conference of 20 August 1956, at which the National Liberation Army (ALN) was officially founded. The setting was also favourable to the expression of pro-independence views. Indeed, 1956 saw the rise of Arab nationalism, following Nasser’s diplomatic victory after the resolution of the Suez Crisis. Along the borders with Morocco and Tunisia, whose independence in 1956 had led to active support for the FLN, ALN units were divided into battalions (failek) of 350 men. Algerian territory was divided up into military regions (wilaya), in which companies (katiba) of 120 men, split into sections (ferkas) of 30 men, were stationed in defensive zones. These were usually located at the intersection of several valleys, so as to enable movement in different directions, and close to a village for supplies. The units were split into small groups entrenched in natural shelters, mostly caves. This strategy based on mobility forced the French Army to scatter its troops across the whole of what was considered “useful” territory.

Between 1955 and 1957, the growth of the ALN gained pace, particularly in the Greater Kabylia and Aureès regions. In 1956, according to Jacques Frémeaux, the Soummam Conference estimated the forces in Algeria at 20 000 men – 7 000 soldiers and 13 000 partisans (La France et l’Algérie en guerre, 1830-1870, 1954-1962, Paris, Économica, 2002, p.150); by August 1957, according to Abane Ramdane, ALN numbers had reached 90 000 men – 50 000 soldiers and 40 000 partisans (Mohamed Harbi, L’Algérie et son destin, croyants ou citoyens, Paris, Arcantères, 1997, pp.109-110). By a year later, in Guy Pervillé’s assessment, French military successes had led to an appreciable drop in the size of independence forces (La guerre d’Algérie, histoire et mémoire, Bordeaux, CRDP Aquitaine, 2008, p.185): 50 000 men, 30 000 of them in Algeria (20 000 soldiers and 10 000 partisans) and 10 000 on the borders (7 500 of them in Tunisia).

This fall in ALN troop numbers meant fewer attacks on French forces. In 1958, these accounted for around a quarter of ALN actions, the other three quarters being terrorist-type attacks on people and property, revealing a weakening of the independence movement’s conventional military capability.

The French Navy’s Penfentenyo Commando in operation in Constantine Province: deployed in August 1955, its mission was to secure the coastal zones which ALN rebels were seeking control over. © B. Pascucci/ECPAD/Défense

In 1954, the French Army had hastily modelled its Algerian strategy on what it had learned in the First Indochina War. It therefore had a poor grasp of the enemy and its modus operandi, so that, particularly in 1955, the French command ordered sporadic, local operations in response to opportunities or emergencies. From 1956 onwards, the army, which had seen a steady rise in troop numbers through the mobilisation of conscripts, succeeded in progressively adapting to the ALN’s actions. In 1958, two objectives (set in 1956) were achieved: to avoid any defeats which the FLN could take advantage of, particularly for internal or international propaganda purposes; to prevent the ALN from developing from commandos carrying out “coup de main” attacks into strong units capable of seeking a confrontation on a par with a conventional conflict. These successes can largely be attributed to two factors: first, the construction of barricades all along the borders, enabling the French to win the “Battle of the Borders” and cut the ALN off from external reinforcements; second, as part of the psychological war, the action of brainwashing within the ALN, weakening it from the inside.

The 18th Chasseurs Parachute Regiment (RCP) in operation at El Ma El Abiod during the Battle of the Borders. In 1958, the 18th RCP took part in 108 operations. © Joubert/ECPAD/Défense

The “Battle of the Borders” and “blueitis”

First it was the “Battle of the Borders”, from January to April 1958 – a result of the completion of the Morice Line, 450 km of mined, electrified barbed-wire fence the length of the borders – which progressively prevented ALN reinforcements from getting through to Algeria. The Morice Line complemented the operation put in place by the French Navy to combat arms trafficking in the Mediterranean. In 1955, it had launched a marine surveillance operation, SURMAR, aimed at preventing arms supplies to the ALN by sea. Then, from 1956 onwards, the Demi-Brigade of Naval Fusiliers (DBFM) reinforced surveillance along the Moroccan border. Whereas in May 1957, the ALN was getting around 1 000 weapons per month across the Tunisian border alone, by early 1958 that figure had fallen to just 100. Refusing to allow the interior army to be caught in a stranglehold, the ALN attempted to break through the barricades between Sakiet and Guelma. Faced with these incursions, General Vanuxem, commander of the eastern zone of Constantine Province, deployed the French reserves, consisting predominantly of paratroopers. The reserves, aided by the troops stationed along the border, would inflict some severe blows on ALN units that attempted to force their way through the blockade. The biggest battle – and the last – was Souk-Ahras, from 28 April to 3 May 1958, which saw more than 1 000 ALN fighters engaged in hand-to-hand fighting against troops of the 9th Chasseurs Parachute Regiment (RCP). The 9th RCP lost a company, commanded by Captain Beaumont (32 dead and 40 wounded), in the attack on Mont Mouadjene (Pierre Montagnon, La guerre d’Algérie, genèse et engrenage d’une tragédie, Paris, Pygmalion, 1984, p.72).

Soldiers of the 2nd Colonial Parachute Regiment (RPC) fight FLN fellaghas in an operation near Malah, March 1958. © S. Berthoud/ECPAD/Défense

But this military victory did not eclipse the political consequences of the bombing of the village of Sakiet Sidi Youssef, in a Tunisia independent since 1956, on 8 February 1958, in the name of the “droit de suite”. This violation of the border and the extent of the civilian losses (69 dead, 130 wounded) led to a major diplomatic setback at the UN, with Paris having to accept a “good offices mission” led by Great Britain and the United States. This sequence of events further intensified criticisms of the Fourth Republic.

Then came the psychological war, and the emblematic infiltration and brainwashing operation KJ-27, nicknamed “blueitis”, which was launched in January 1958, following the Battle of Algiers (January to October 1957), by the secret service of the Foreign Documentation and Counter-Espionage Service (SDECE). This operation sought to neutralise the ALN’s military action and human potential. Led by Captain Paul-Alain Léger, its priority target was Colonel Amirouche, commander of wilaya III in Kabylia. Convinced that his sector was infiltrated by double agents converted to the French cause, Amirouche carried out a major, bloody wave of purges among the ranks of the independence fighters. The other wilayas were soon affected by these purges, which went on into 1961. This success, described in detail by Charles-Robert Ageron (‘Complots et purges dans l’armée de libération algérienne (1958-1961)’, in Vingtième Siècle, revue d’histoire, no 59, July-September 1998, p.15-27), had, in the short term, a devastating effect on combatants’ morale and, in the long term, resulted in the loss of a whole generation of cadres, a shortage that was to be felt by the FLN. Figures are difficult to establish; Rémy Madoui (J’ai été fellagha, officier français et déserteur, du FLN à l’OAS, Paris, Seuil, 2004, p.98) estimates that 7 000 ALN members were eliminated during these purges (the majority former city-dwelling graduates), while Henri Le Mire (Histoire militaire de la guerre d’Algérie, Paris, Albin Michel, 1982, p.386) puts that figure at 15 000.

Militarily, then, the situation stabilised in 1958, at a cost of violent confrontations, but the French diplomatic situation continued to deteriorate, while political instability exasperated a growing sector of public opinion. Faced with the wait-and-see attitude of the majority of the metropolitan population, and the divergences of the Muslim population on the issue of independence, those who were anti-independence (the vast majority of Algeria’s European population) were losing patience with the lack of a clear, coherent stance from politicians to keep Algeria in French hands.

“I have understood you”

Politically, 1958 was marked by an active search for a stable government, capable of putting an end to the conflict. The crisis of 13 May 1958 brought the return of General de Gaulle, who was seen by all parties as a solution and a defence against the Fourth Republic’s inability to resolve the Algerian crisis. De Gaulle established the Fifth Republic in October 1958, providing the conditions for political stability while maintaining a certain ambiguity as to his intentions regarding Algeria. The beginning of 1958 was characterised, on the one hand, by the political authorities’ inability to cater to the aspirations of proponents of French Algeria and, on the other, reports of the use of torture by the French Army by a minority of intellectuals, like Henri Alleg (La Question, Lausanne, Éditions de la Cité, 1958) or Jean-Pierre Vernant (Raphaëlle Branche, La torture et l’armée pendant la guerre d’Algérie, Paris, Gallimard, 2001).

Jacques Soustelle, governor-general of Algeria from 1 February 1955 to 30 January 1956, receives a triumphal welcome to Algiers, May 1958. © ECPAD/Défense

The way the 1956 Suez Crisis was handled by Guy Mollet’s government (January 1956 to May 1957), and the subsequent handling of the Sakiet Sidi Youssef case by the Félix Gaillard administration (September 1957 to April 1958), triggered major tensions between supporters of French Algeria, in particular the Algiers military command, and the politicians in power. On 13 May 1958, the imminent swearing-in of Pierre Pflimlin, a known advocate of negotiating with the FLN, as prime minister, prompted supporters of French Algeria to carry out a coup from Algiers. They formed a “Committee of Public Safety” with General Massu at its head, supported by General Salan, commander-in-chief of the armed forces in Algeria, who had been the government’s general representative from the onset of the crisis. On 1 June 1958, in response to pressure from Salan, the French president, René Coty, appointed General de Gaulle as head of government. De Gaulle cleverly took advantage of the deteriorating situation in Algeria and the development of the anti-independence movement, sending signals to pro-French Algeria supporters while at the same time posing as the solution to advocates of Republican legality. De Gaulle’s subsequent declarations, in Algiers on 4 June (“I have understood you”) and Mostaganem on 6 June (“Long live French Algeria”), reassured the anti-independence camp, who now felt that the clear aim of the war was to hold onto Algeria. However, Guy Pervillé asserts that, in June 1958, de Gaulle believed that Algeria would one day separate from France, though he did not know by what means or with what partners he might conduct that process.

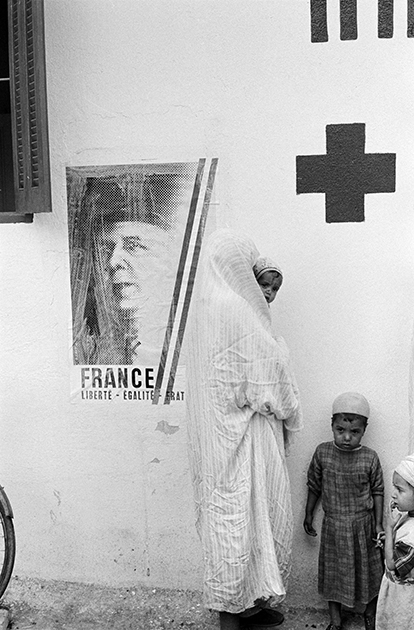

Referendum campaign for the Constitution of the Fifth Republic, entrance to an infirmary, Mitidja, 1958. © Jean Marquis/Roger-Viollet

October 1958: a change in Paris’s Algerian policy

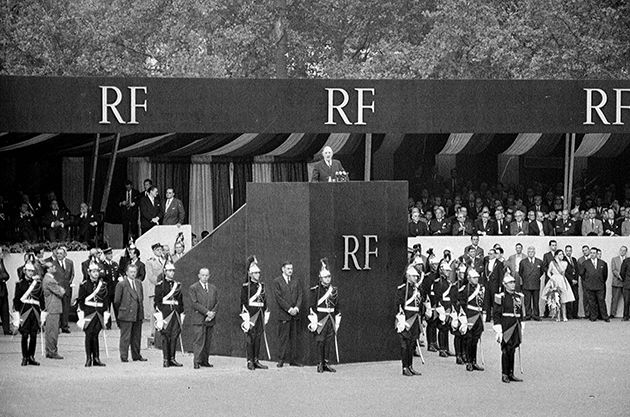

The drafting of the Constitution of the Fifth Republic catered to General de Gaulle’s desire to bring government instability to an end, put a stop to the threat of a military coup and find a way out of the Algerian quagmire. The first consequence was to impose the primacy of universal suffrage as the legitimate source of power and, therefore, as the final arbiter of the end of the conflict. The draft constitution put to a referendum on 28 September 1958 was passed by a big majority of 79.25%. Henceforth, the popular vote would play a predominant role in de Gaulle’s Algerian policy. In January 1961 (referendum on self-determination in Algeria) and April 1962 (referendum on the Évian Accords), electors enacted the move towards self-determination and independence.

The second consequence was to restore the stability and primacy of the executive, embodied by General de Gaulle, who, since late 1958, had altered the intransigent line taken by Paris vis-à-vis the independence movement since 1954. The announcement of the Constantine Plan, on 3 October 1958, may have been interpreted by pro-French Algeria supporters as an indication of his desire to stay in Algeria, but it soon became clear that by reaffirming the pre-eminence of civilian authority over military authority de Gaulle was broadening the options for the end of the conflict. After the legislative elections of 30 November 1958 highlighted General Salan’s reluctance to bend to the government’s demands, a new general representative, Paul Delouvrier, was appointed on 12 December 1958. Delouvrier recovered the political prerogatives that had been entrusted to Salan. Salan was also replaced as commander-in-chief by General Challe, whose role was now confined to the military sphere. Challe was tasked with achieving victory on the ground by implementing a plan which he launched in January 1959. The goal was to provide General de Gaulle with a strong position from which to negotiate with the FLN, who had refused the Paix des Braves (“Peace of the Brave”) offered at the press conference of 23 October.

The third consequence of the arrival of the Fifth Republic was the restructuring of the FLN with the proclamation of the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA), which emerged out of the Committee of Coordination and Enforcement (CCE), an embryo of executive power set up at the Soumman Conference, on 20 August 1956. The choice of date for the announcement, 19 September 1958, a few days before the referendum on the adoption of the Constitution, was probably not insignificant and amounted to an attempt at regaining the lost initiative in the military and political spheres. The head of the GPRA, Fehrat Abbas, a prominent moderate, contributed to giving it a positive image overseas. The proclamation of the GPRA was part of a process of radicalisation of the FLN aimed at imposing independence, in opposition to the announcement of an association with Paris within the Community set out in the new Constitution. In addition, the decision to reject any solution other than independence led the FLN to take the conflict to metropolitan France with the “Battle of Paris”, from 25 August to 25 September 1958. “Exporting” the conflict to the capital made up for the military retreat on Algerian soil and enabled the FLN to try to obtain the support of public opinion in France to shape the Algerian policy decided by the man who embodied the new Republic..

General de Gaulle’s speech presenting the Constitution of the Fifth Republic, Place de la République, Paris, 4 September 1958. © Bernard Lipnitzki/Roger-Viollet

Thus, 1958 saw France regain the initiative on all fronts. Militarily, the independence movement did not succeed in checking the stranglehold on the interior army, largely because the borders had been practically sealed off. Politically, since the events of May 1958 which brought General de Gaulle to power, the FLN had been worried about the possible consequences of de Gaulle’s popularity for settling the conflict, and also those of the new Constitution of October 1958. Given the French and Algerians’ desire for peace, General de Gaulle believed that a solution of autonomy as a French territory was possible. A year later, after his attempts at negotiation had failed, he seemed to decide that only the practical terms of recognition of full independence could form the basis of a compromise with the FLN.