The “Battle of the Hedgerows”

As a result, the Americans suffered dreadful losses: between 3 and 14 July 1944, Middleton’s VIII Corps advanced six miles at a cost of 10 000 men, or one man per yard gained. Collins’s VII Corps fared no better, with 7 000 US soldiers being killed between 4 and 9 July. During the first two weeks of July, Bradley’s First Army lost a total of 40 000 men, 90% of them infantrymen. But the bloodshed was equally high on the German side, with a number of battalions of the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division Götz von Berlichingen losing two-thirds of their men. It is true that the losses on the American side were replaced, but the new arrivals were often inexperienced. In all, nearly half of US troops had never seen combat before Normandy. Losses among these soldiers who had their baptism of fire in the hell of the hedgerows were considerably higher than for experienced soldiers. In addition to the physical wounds came the psychological ones: the brutality of this war, the unique conditions in which it took place, fatigue, fear and the constant presence of death were such that neuropsychiatric disorders alone represented 12% of admissions to US field hospitals in Normandy.

Meanwhile, on the German side, reinforcements were far lower than the losses, as noted by General Rommel in his report to Hitler of 17 July 1944: “Regarding the losses we have sustained: 97 000 men, including 2 360 officers, i.e. 2 500 to 3 000 men per day; the reinforcements received to date have been only 10 000 men, and of those only 6 000 have so far reached the firing line. Our material losses are huge and have been replaced only in a reduced proportion; for instance, we have received a total of 17 tanks to replace the 225 tanks lost.” That very day, Rommel was seriously wounded when his car was attacked by an Allied aircraft. Like most German generals, he sensed the collapse of the Wehrmacht in the West. In the end, it was Operation Cobra, a large-scale offensive carried out from 25 to 31 July 1944, that enabled the First United States Army to break free from the bocage.

Aerial view of the Normandy bocage and its characteristic landscape of hedgerows. Copyright private collection

A German paratrooper and his MG 42 machine gun, in Normandy, summer 1944. Copyright Bundesarchiv

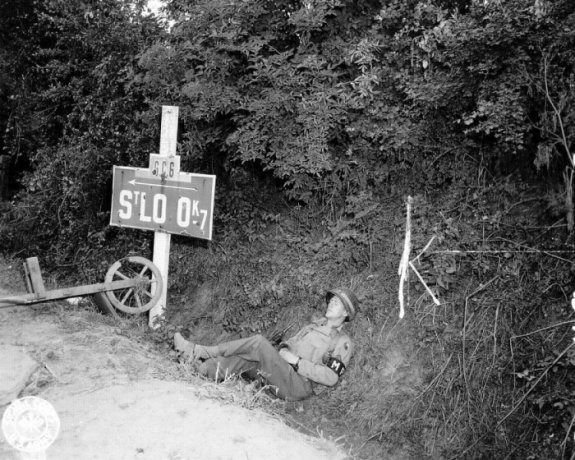

An American GI rests near Saint-Lô, summer 1944. Copyright US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

Copyright US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

A Sherman M4 Rhino tank fitted with a device for cutting through hedges. Copyright US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

American GIs advance through a gap in the hedge made by a Rhino tank. Normandy, June/July 1944 Copyright US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

Three US soldiers advance along a hedgerow typical of the Normandy bocage, June/July 1944. Copyright US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

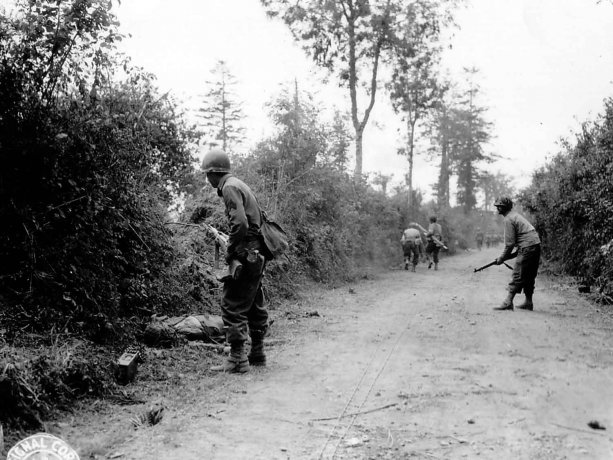

An American patrol on a country lane in Normandy, June/July 1944. Copyright US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)