The colonised soldiers of the French Empire

Sous-titre

19th and 20th centuries

From the colonial wars of the 19th century to the end of the wars of decolonisation in the middle of the 20th, the army progressively institutionalised the recruitment of men among the populations over which France was establishing, then consolidating, then finally seeking to preserve its dominion. Those men, recruited using different methods depending on the period and place, fought under the tricolour flag in both the world wars, across the French Empire and Europe alike. From the mid-19th to the mid-20th century, the French army can thus be considered an imperial and colonial army.

From the colonial wars of the 19th century until the wars of decolonisation in the second half of the 20th, the French military recruited from among local populations, in an increasingly institutionalised process, in order to impose, build and ultimately maintain colonial order. Given a variety of names throughout this period – “natives”, “Muslims”, “North Africans”, “French Muslims”, “colonial troops”, “Senegalese tirailleurs” – to distinguish them from the “Europeans”, the soldiers recruited in the Empire did not enjoy all the rights associated with citizenship. A wide variety of different recruitment procedures were used across the Empire, which depended in part on the status of the territory – colony, protectorate or department, in the case of Algeria. The recruitment of these soldiers reveals, on the one hand, how the army was a fully colonial institution that distinguished between citizens and subjects, and also how it was founded on a derogation from the Republican principle tying “blood tax” to citizenship, despite the fact that it was instituting military service. Aside from what were in some cases wildly different backgrounds, combat experiences and recruitment methods, these soldiers therefore shared the status of being “colonised”, hence the use of the term “colonised soldiers”.

From the colonial wars to the European battlefields: the progressive institutionalisation of recruitment of colonised soldiers

As far back as the colonial wars of the 19th century, the French army enlisted men to make up for a shortage of European troops, to begin with to complete the conquest, and later to maintain colonial order. The Algerian tirailleur units were founded in 1842 and, in 1857, the Senegalese tirailleur corps, comprised of volunteers from across sub-Saharan Africa. During the conquest of Madagascar, beginning in 1894, two regiments of Algerian tirailleurs and one colonial regiment comprising colonised soldiers from Africa, Malagasies and Reunionese fought in an expeditionary corps.

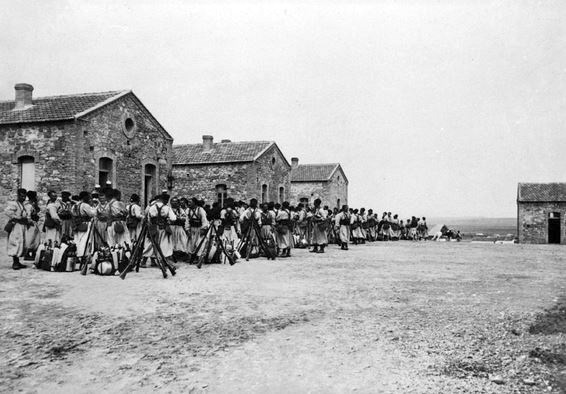

Images of French forces in eastern Morocco, 1906-12: zouaves at the Oujda camp. ECPAD/Aristide Coulombier

It is true that colonised soldiers were occasionally used in Europe, in the Crimean War (1853-56) and the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). But it was not until the First World War that the recruitment of colonised soldiers by the French army and their deployment on the European battlefields became institutionalised, as General Charles Mangin had advocated in his essay La force noire (Black forces), published in 1911. In 1913, special decrees gave powers to recruit throughout the Empire. While figures vary, it can be estimated that 545 240 colonised troops were mobilised, around 437 500 of which were sent to Europe. Algeria and French West Africa (AOF) were the imperial territories that provided the most men.

Algerian tirailleurs, or Turcos (Turks). Uniform in 1852: Algerian drummer, Algerian officer, French officer (flag), Algerian soldier (rifle), canteen keeper.

This unprecedented mobilisation revived the debate about conscription in the colonies, which was not looked on favourably, particularly in Algeria, by Europeans who were concerned about a shortage of labour and fearful that conscripts would be rewarded with rights. Conscription in Algeria was passed in 1912, though, in practice, it was subject to specific provisions, such as the system of drawing lots. In sub-Saharan Africa, the decree of 30 July 1919 introduced the principle of three years’ military service but, far from being universal, this conscription was based on a lot system. French Equatorial Africa (AEF) was exempted from the conscription system in 1928. The process of militarisation of African colonial societies prompted resistance, in the AOF in 1915 and Aurès (Algeria) in 1916. But the Senegalese member of parliament Blaise Diagne, a fervent assimilationist, appointed as the government’s high commissioner for the recruitment of colonial troops, succeeded in recruiting 77 000 soldiers in sub-Saharan African in 1918.

From defeat to victory: colonised soldiers, key to the French army’s revival in the Second World War

In 1939, Africa was once again seen as a pool of soldiers on which to draw and, in March 1940, some 340 000 colonial subjects were conscripted. Although not all of them were sent to Europe when the French army was defeated by the Wehrmacht, 70 000 North Africans and 40 000 to 65 000 sub-Saharan Africans fought in the campaign of 1940. Their fate was often tragic: those who were not massacred by the German army spent years in captivity on French soil, guarded by French police. Soon, however, the AEF and Cameroon joined Free France and entered the war once again. In September 1940, 3 000 European and 4 000 colonised volunteers joined the ranks of the Free French Forces (FFL). In December 1942, French Somaliland supplied 900 European and 1 500 African soldiers. Although the colonised FFL troops were officially volunteers, this was not always the case, since Free France used forced conscription in the territories under its control. The Allied landings in North Africa, in November 1942, signalled a large-scale mobilisation: 134 000 Algerians, 26 000 Tunisians and 73 000 Moroccans joined the ranks, while the AOF and AEF supplied 80 000 men. They fought first of all in the Tunisian (1943) and Italian (1943-44) campaigns, then took part in the Provence landings beginning on 15 August 1944, liberating southeastern France before going on to fight in the Vosges and Alsace, then finally participating in the invasion of Germany in spring 1945. They therefore played a prominent role in the liberation of metropolitan France.

Column of Senegalese tirailleurs, April 1940. © ECPAD

Revising its “theory of martial races”, the army now gave preference to the recruitment of colonised troops from North Africa, considered inherently better soldiers than sub-Saharan Africans. That was one of the reasons behind the withdrawal of sub-Saharan African troops from the front in autumn 1944 – termed “whitening” – in addition to the political authorities’ desire to “metropolitanise” the military forces, by incorporating thousands of French Forces of the Interior (FFI) volunteers. To the military hierarchy, the colonised soldiers required leadership from an experienced European officer, with concern for the well-being of his men. Very few colonial subjects reached officer rank. This was because the army was run in a paternalistic way, rooted in racial prejudices. However, in a context of weakening colonial power since the defeat of 1940, the French Committee for National Liberation (CFLN) now had to negotiate the mobilisation of colonised troops with Algerian nationalist leaders. In 1943, the CFLN therefore introduced equal salaries, although this did not include dependants’ allowance. As a result, the colonised soldiers showed great loyalty in action throughout the second French campaign, despite being mobilised in some cases for several years without leave. Once they had done their duty, all the men wanted was to go home. Therefore, it was clearly a profound sense of injustice rather than nationalist demands that lay behind the protests and mutinies which erupted at the end of the war and were violently repressed by the French army, as in Thiaroyé, Senegal, in November and December 1944.

Liberation of Marseille: Moroccan goumiers advance on the city. Source: SHD

The end of an empire: colonised soldiers in the wars of decolonisation

After the end of the Second World War, these soldiers were once again employed as an armed force, to prop up an increasingly contested colonial order. For instance, Senegalese tirailleurs were sent to put down the independence movement in French-mandated Syria in 1945 and, in 1947, to combat Malagasy insurgents. Meanwhile, a now wary military hierarchy initially ruled out the use of sub-Saharan African soldiers in the First Indochina War. Yet, faced with a shortage of European volunteers willing to fight in a distant conflict, it resorted to using first North Africans then, in 1947-48, sub-Saharan African soldiers. Thus, 75 000 Moroccan troops served in Indochina between 1947 and 1956. At the same time, from the outbreak of the war, the French army recruited heavily from among ethnic groups hostile to the Viet Minh. By 1954, there were some 75 000 auxiliaries, in addition to tens of thousands of regular Vietnamese soldiers in the expeditionary corps.

A Tai unit takes up its position. Source: ECPAD France

During the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62), 100 000 “French of North African origin”, as they were known, did their military service in the French army, because the Lamine-Gueye Act, which entitled all nationals of the Empire to French citizenship, and the adoption of the Statute of Algeria, in 1947, made all Algerians subject to the same military obligations as the metropolitan French. Some served in the regular army, while others joined auxiliary units, like the harkas. Recruited locally, they gave the French army an advantage in this war viewed as “counter-revolutionary”, although it was as much about winning over the people as controlling the territory. Such an engagement earned these men, known as harkis, the status of traitors in the eyes of their compatriots, so that, following the Évian Accords of March 1962, they were forced into exile in France, where they lived a precarious existence in transit and reclassification camps, like Rivesaltes, in the Hérault.

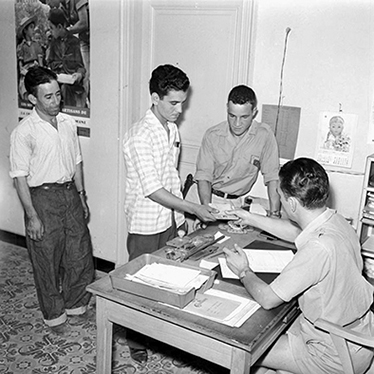

Harki applicants report to the Palestro office, in Kabylia, to sign a contract to enlist in the French army. © ECPAD

Towards the construction of shared remembrance?

According to historian Julie Le Gac, the engagement of these colonised troops in the French army in the wars of independence cast a thick veil over the shared military past of France and its former colonies during the two world wars. In Morocco, the soldiers’ participation in the fighting for Liberation is presented as a response to the appeal by Sultan Mohammed V, and therefore as a form of patriotism, thus avoiding any conflict with France over remembrance. Meanwhile, in Algeria, enlistment in the French army during the two world wars is presented as the very expression of colonial oppression. Since the 2000s, remembrance of these men has focused on the issue of veterans’ pensions. Initially frozen at a fixed rate decided upon during independence negotiations, pensions did indeed create inequalities between French and former colonised veterans. From the late 1970s, veterans fought for their rights, and ultimately succeeded in having their pensions revised in 2002. When Rachid Bouchareb’s film Indigènes (English title: Days of Glory) came out in 2006, President Chirac announced the complete unfreezing of the pensions, which was finally concluded in 2010. The key issue since then has been to recognise the role played by colonised soldiers in the liberation of Europe, and the mistakes made by the former colonial power: the process of constructing shared remembrance on either side of the Mediterranean now appears to be firmly under way, though it has not been plain sailing. On a visit to Senegal in November 2012, President Hollande denounced the injustice of the repression of Thiaroyé, in the light of the engagement of sub-Saharan African soldiers, who, he said, bear “this debt of blood that unites France with a number of African countries”. In a clear sign of the extent of public concern for the fates of former colonised soldiers, in 2017, following a petition signed by 60 000 people, 28 former tirailleurs from sub-Saharan Africa who served in Indochina and Algeria were granted French citizenship, in a ceremony at the Élysée Palace.