Europe in face of the Yugoslav crisis

International relations expert Pierre Hassner likened the Cold War to a ”refrigerator effect”. If, for nearly half a century, the East-West standoff had ”frozen” regional complexities, the disappearance of that climate in the 1990s brought a resurgence of old animosities and marked the return of ”strategic disarray” during the war in the former Yugoslavia.

In August 1990, when all eyes were on the invasion of Kuwait by Saddam Hussein, the powder keg of the Balkans was set to symbolise the strategic disarray of the 1990s, in the face of an ultra-nationalist programme thought to be no longer conceivable just a two-hour flight away from Paris. Confronted with the determination of a man like Slobodan Milosevic, the UN paled into insignificance. NATO was slow to take action and our US allies prevaricated. Meanwhile, the EU had to relativise its ambition to constitute an international actor simply as a result of the Maastricht Treaty. This strategic disarray brought moral disarray which could be entitled ”from Sarajevo to Sarajevo”. From the 1914 assassination to the bombing of a market in the city by Serbian troops in February 1994, had Europe not committed political ”suicide” once more? After the terrible episodes of the 1991 breakup of Yugoslavia, such as the siege of Vukovar and the discovery of Serbian concentration camps in Bosnia, nothing will erase the feeling of European failure and international impotence, despite François Mitterrand's visit to Sarajevo in June 1992 and the setting up of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 1993. During the Serbian provocations of spring and summer 1995 (370 UN peacekeepers taken hostage, offensive against ”safe zones”, Srebrenica massacre), the Allies were confronted with the complexity of the terrain - led by France and Great Britain, soon joined by the United States.

First signs of a world in turmoil

From the Titoist schism to the Non-Aligned Movement, we had ended up believing that the bipolar period had given credit to the Yugoslav federation. Balkan complexity, with its Serb, Croat, Slovene, Macedonian, Montenegrin, Bosnian and other differences, had been relegated to the distant past. That complexity re-emerged from the ”refrigerator” of history, all but intact. In the same way, the South, considered the playground for an East-West confrontation, regained its subtleties. In 1992, Somalia - formerly an element in the see-saw game between the two superpowers, like neighbouring Ethiopia - became a new US quagmire, putting an end to any unipolar illusion (1991-92). The dissidence of a Saudi citizen named Osama Bin Laden against the authorities of his home country, whom he did not forgive for receiving US troops as part of Operation Desert Storm, together with the interruption of elections in Algeria by the army, would provide new demonstrations of a sudden development in international relations in which, now that the Cold War was over, local actors had ceased to be mere pawns in the hands of the superpowers. But had they ever been, other than in the optical illusion entertained in the North? In the face of these new circumstances, the strategic concepts inherited from the Cold War lost their meaning. What was meant by the concept of power, in 1992, when the United States was under attack from the obscure General Aideed in Somalia? Or the concept of victory, when Saddam Hussein, ”beaten” the previous year, once more brutally suppressed Iraqi Shiites in the south of the country? What were power relations made of if Serbia could defy the international community with impunity, humiliating UN peacekeepers, flouting the ethical promises of the post-war world and scoffing at its European neighbours, two of which were nuclear powers?

1992, then, was a pivotal year for a much-needed revision of doctrines. The French army learnt lessons from the Gulf War in terms of military hardware, from the Yugoslav conflict in terms of type of engagement, and even questioned the role of nuclear deterrence in a post-bipolar world that was now a planetary village. In this context, France announced a moratorium on French nuclear testing. Ultimately, 1992 had the effect of highlighting the importance of rapid response, effective projection and the chosen political/military combination. And, consequently, it saw the re-emergence of all the complexity of a now multiple world.

Frédéric Charillon - Lecturer in political science,

Director of the Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l'École Militaire (IRSEM)

in Les Chemins de la Mémoire, no 227/June 2012

See also on Educ@Def: Overseas operations

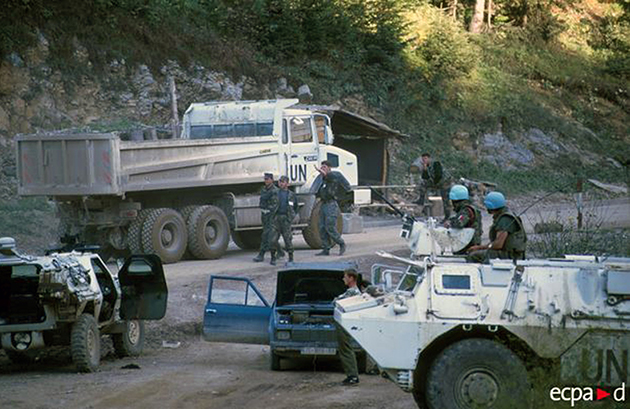

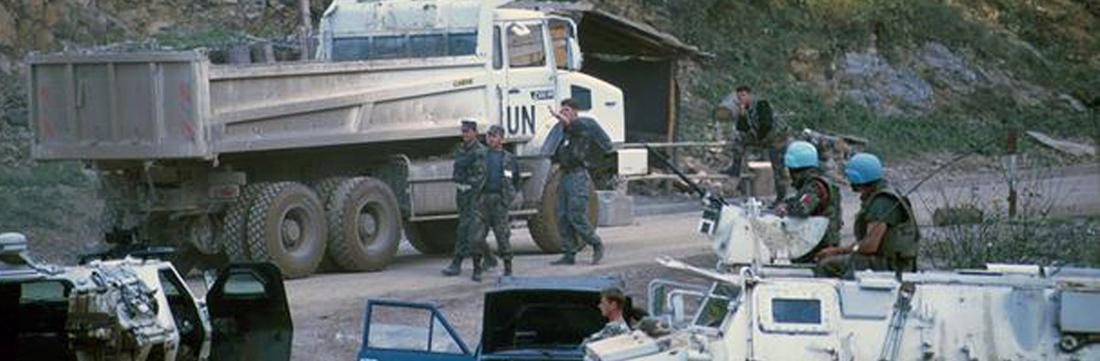

Les véhicules militaires et les blindés du 1er RIMa (régiment d'infanterie de marine) et du 126e RI (régiment d'infanterie) sont rassemblés à leur arrivée sur l'autodrome de Rijeka. De couleur blanche et siglés UN (Nations Unies), ils sont destinés aux missions du bataillon français d'escorte des convois humanitaires de la Forpronu, Croatie, octobre 1992.

©ECPAD/Claude Savriacouty

À l'occasion de la visite à Sarajevo de Boutros Boutros-Ghali, secrétaire général de l'ONU, des habitants manifestent devant la présidence bosniaque. Lassés de l'inefficacité de l'intervention des Casques bleus dans le conflit, ils brandissent des pancartes rédigées en anglais, demandant une aide plus efficace aux militaires de la Forpronu ou leur départ, décembre 1992.

©ECPAD/Claude Savriacouty