The Korean War sixty years on: history and remembrance

Breaking out on 25 June 1950, the Korean War was a major conflict of the Cold War and one of the deadliest in the second half of the 20th century.

The war also represented a first test for the UN which, to prevent the outbreak of a third world war, appealed to its member states to form an international army. France's involvement, by sending a battalion of military volunteers that proved its valour on a number of occasions, paved the way for the Opex (overseas operations of the French military) and sealed its partnership with South Korea.

American soldiers in Korea, November 1950. Source: US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain

At the end of the Second World War, the decision to divide Korea into two temporarily-occupied zones—one by Soviet forces, one by American forces, without taking into consideration the actual wishes of the Korean population—led to the partitioning of a country that had been unified since the 7th century. The Cold War favoured the establishment of divided states and the failure of negotiations involving the Soviet-American Joint Committee. The UN's albeit flawed attempts to arbitrate failed to prevent the formation of two Korean states in 1948. Accordingly, assisted by the desire for reunification and the crystallisation of the confrontation between the two camps, the Korean War was declared on 25 June 1950 following a long and complex decision-making process, marked by Stalin's prudence and the development of the international situation in East Asia.

Soviet T-34 tank of the North Korean People's Army in Suwon, put out of action by the air force on 7 October 1950. Source: Federal government of the United States of America, photo in the public domain.

The Soviets, on the behest of the North Korean government, had equipped the country with a proper army endowed with planes and armoured vehicles, while the Americans had supplied South Korea with neither armoured vehicles nor heavy artillery, considering the South Korean army as an interior force for maintaining order and not a front-line army: Washington feared reinforcing the troops of Syngman Rheedi (1) who was also an enthusiastic supporter of reunifying the peninsula. However, a large proportion of popular sympathies supported left-wing doctrines in a still traditional country, although the South Koreans were far from firmly grasping the subtleties of Marxist dialectics.

Simple social justice, the sharing of land when the agrarian reform had already been declared in the northern territory, unemployment and economic crisis that ensued following the separation of the industrial north from the fundamentally agricultural south all contributed to exacerbating the political rifts and grievances. Furthermore, the police, inheritors of the Japanese Kempeitai ('military police corps'), was known for its brutality, quasi-systematic use of torture and an unfortunate propensity for firing into the crowd.

Syngman Rhee, May 1951. Source: Federal government of the United States of America, photo in the public domain.

Following various episodes of police brutality, a communist revolt erupted on Jeju Island off the south coast of the Korean peninsula in April 1948 and a constabulary regiment mutinied in October. The attempts to quell these uprisings, by the police but also auxiliary forces made up of anti-communist radicals, often refugees from North Korea, unruly and unpaid, prompted a spiral of violence and repression that called the legitimacy of Syngman Rhee's government into question.

On 25 June 1950, North Korean troops invaded the territory of South Korea and started a long conflict lasting ”three years, seven months and 27 days” (2) that finally ended in July 1953. The war was one of the most serious world events since the Nazi surrender, despite the Greek and Iranian crises and the Berlin blockade.

In the minds of Western governments and America's in particular, this attack could only be a new manoeuvre by Stalin.

Kim Il-sung in 1946. Source: Korean People Journal, public domain.

In actual fact, the leader of North Korea Kim II-sung had decided in 1948 to reunify Korea by military means for lack of any other legitimate measure to engineer the unification of the Korean nation. Stalin initially refused, instead intent on maintaining peace at the border between the north and south. Mao's victory and the foundation of the People's Republic of China along with the success of the Soviet atomic bomb caused Stalin to reconsider his strategic vision. Fearing a rapprochement between China and the United States, he had the idea, according to the findings of recent research, to weaken both his allies and his enemies by encouraging a confrontation between them and Korea.

This conflict, ironically spawned from a civil war waged between two artificial States each pleading their right to govern the other, rapidly transformed into an international matter when the UN Security Council made an appeal to create an ”international police force” organised under the aegis of the UN and led by the US (the contributor of the biggest UN contingent sent out to Korea), in accordance with the Security Council's resolutions of 27 June and 7 July 1950.

Thus started one of the worst conflicts in what became known as the ”Cold War”, an expression that gained popularity inversely proportional to the success of the campaign, and one of the bloodiest wars of the 20th century. Within three days, the North Korean armed forces seized an almost deserted Seoul. By late August, while the US had started to transfer poorly-armed troops from Japan, nothing appeared to be able to stop the victorious northern armies flooding towards the south. But the Americans and the South Koreans finally succeeded in holding on to the defence line along the Nak-dong River that protected the Pusan Perimeter. Meanwhile, General MacArthur and the Pentagon arranged the provision of supplies and equipment and 16 countries responded to the UN appeal. The United States, Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Thailand, Columbia, Ethiopia, Greece, Turkey, the Philippines and Luxemburg all contributed military resources to the UN effort. Other countries supplied hospital ships.

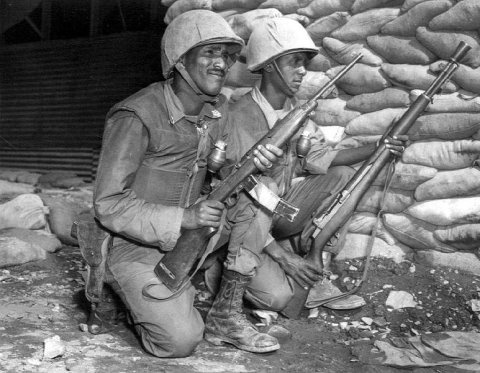

Ethiopian soldiers with an M-1 rifle, in Korea 1953. Source: United States Army Heritage and Education Center, photo in public domain.

Luxemburgish soldier in Korea, 1953. Source U.S. Defenseimagery.mil photo, photo in public domain.

France, despite deep reservations caused by the significant losses in Indochina and western Europe's rearmament plan, finally agreed to send troops. René Pleven (3) and Jean Létourneau (4) understood that France should not only uphold its international rank but also show a pledge of military solidarity and political constancy if it wished to claim American aid in Indochina or in Europe; France also agreed to create a ”battalion of volunteers”.

French battalion's base camp in Kapyong. Source: ECPAD

Trained in Auvours (Sarthe), the UN's French battalion in Korea was integrated into a unit named the French Land Force composed of general staff supported by specialists and an infantry battalion. The Minister of Defence intended to take advantage of the opportunity to conduct an information mission, in particular concerning the strengths and weaknesses of American armoured vehicles compared with Soviet tanks, the use of tactical aviation and the struggle against the cold. The battalion was composed of volunteers from active and reserve units, with priority given to ”reservists” who had already been on a campaign, of which there were many five years after the end of the Second World War and the war in Indochina being in full swing.

While the French volunteers were still being trained in France, General MacArthur, who had received adequate reinforcements, launched an amphibious operation against Inchon, the port of Seoul, on 15 September while the forces in the Pusan Perimeter went on the offensive.

MacArthur on 21 August 1950, just before the Inchon invasion. Source: Federal government of the United States of America, photo in the public domain.

By the end of the month, most of the South Korean territory had been liberated and President Rhee was able to return to a war torn Seoul. While South Korea was liberated, despite the presence of communist maquis that welcomed the remnants of the North Korean army trapped by Operation Inchon and the recapture, neither Syngman Rhee nor MacArthur had any intention of leaving things there. During the first days of October, the South Korean army started to advance towards the 38th parallel north. They were joined by American troops as soon as the UN voted a resolution to authorise the breaching of this line.

The UN army soon captured Pyongyang but by winter 1950, while the North Korean government had taken refuge at its border, China, after several warnings, sent an army of volunteers to come to the rescue of a flailing People's Republic of Korea.

Evacuation of North African refugees by the US Navy, 1952. Source: Federal government of the United States of America, photo in the public domain.

The UN and South Korean forces were obliged to retreat faced with the powerful Chinese offensive whose troops took skilful advantage of the rough terrain and the weather conditions. In January, Seoul was once again evacuated under the unstoppable pressure mounted by the Chinese volunteer soldiers. The Americans managed to recover from February, under the command of General Ridgway. The slow recapture of the territory lost by the Americans, from spring 1951 onwards, and their success in the airborne war allowed troops to gradually progress to the 38th parallel.

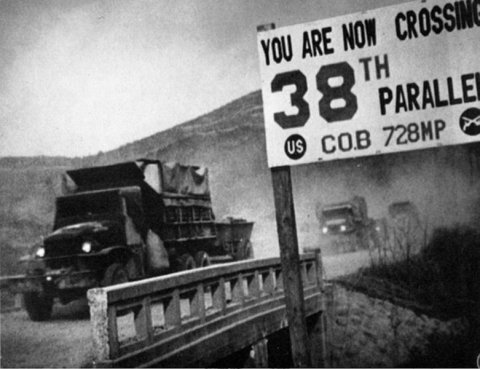

Contre-offensive de l'ONU, franchissement de la frontière au niveau du 38e parallèle nord, le 11 mai 1952. Source : US National Archives and Records Administration. Libre de droit

The fighting thus broke out on a front line that ran more or less along this artificial dividing line. Truman refused the extreme warmongering of MacArthur who supported all-out war and his resounding announcements that put Washington's policy at risk and eventually dismissed the old generalissimo. Some of the tensions died down and the communists agreed to negotiate. First in Kaesong, and then in Panmunjom, these negotiations were hindered by numerous incidents and interruptions. The issue of the repatriation of war prisoners soon posed a problem after the Allies established the principle of free choice with regard to the destination of repatriation and tens of thousands of communist prisoners decided they did not want to return home. The talks broke down several times.

UN counter offensive, breaching of the border at the 38th parallel north, 11 May 1952. Source: US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain.

However, the war waged on, notably seeing American bombings of North Korea that destroyed 80% of the state's towns and factories. This destruction, a massive blow to the Chinese and North Koreans who lost huge numbers of men, prompted the Soviets to send significant resources in terms of equipment, pilots and mechanics. Soon, whole anti-aircraft defence units were deployed to North Korea and attempted to clear the skies of UN army aircraft while communist artillery intensified.

In this sense, the Korean War was the major conflict of the Cold War, since the Soviet and American air forces were in direct confrontation for at least two years over Korean territory.

However, everything was done, in Washington as in Moscow, to overshadow this aspect of the conflict by shielding the public from the existence of direct fighting and avoid widespread unrest. Thus MacArthur's plans to bombard China or resort to atomic weapons were finally withdrawn from the strategic options. Similarly, the incidents during which Soviet planes were shot down by American aerial pursuit by error were largely suppressed since neither of the two powers wished to start a third world war.

M4A3E8 ”Sherman” in firing position on a hill, May 1952. Source: US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain.

Following Stalin's death in March 1953, negotiations progressed more rapidly, the Kremlin wishing to quell certain tensions in Asia and Europe. In July, the armistice was finally signed by the main warring parties, ending a conflict that caused two to three million deaths in three years and eight months of warfare.

For the UN's French battalion, the Korean War was an opportunity to prove its valour. During the battalion's three years in service, this marching unit won glory in places such as Chipyong-ni and the Twin-tunnels, Hill 1037, Putchaeteul, Crèvecoeur and Arrowhead. According to expert opinion and as confirmed by two Korean Presidential honours, three American honours and a plethora of French honours, the UN French battalion was the most decorated UN army and never once abandoned its positions nor retreated from the enemy. Yet, despite this impressive result, and while the French contribution to the Korean War also gave rise to the French ”Opex” tradition (5) at the service of the UN, the memory of its dazzling achievements has since long fallen into obscurity. After modest beginnings in 1948, when it oversaw the truce of the Arab-Israeli conflict, France saw the Korean War as an opportunity to take a much greater role in UN operations. A commitment that it has stuck by right through to today, since in 1995 France was the number one contributor of peace-keeping forces with the deployment of 5,000 men (6) around the world. Today, the number earmarked for international operations total 8,800 men deployed all over the world. A ”remembrance trail” has been built since 2007 in South Korea through actual sites of combat and the main French bivouacs thanks to a partnership established between ANAAFF/ONU (the national association for veterans and friends of the UN French Forces), the Korean association for the memory of France's participation in the Korean War and various French and Korean organisations and foundations. In addition to the monument in Suwon, the monument dedicated to commander and doctor Jules Jean-Louis (the third statue erected in honour of a foreigner in the whole of South Korea), the United Nations cemetery in Pusan and the lists of names displayed on the Seoul War Memorial, the remembrance trail comprises commemorative steles and plaques paying tribute in French, Korean and English to the sacrifice paid by the French battalion during their time in South Korea, under the banner of 'liberty'. At various ceremonies, the pupils of the French lycée in Seoul and those from neighbouring schools take part in events that revive and reinforce the perception of France as a partner and friend of South Korea.

Volontaire du BF/ONU à l'entrée du camp, juin 1952. Source : ECPAD

A South Korean ambassador in France recently declared that in recognition of the French battalion's stationing in Korea and the establishment of Franco-Korean relations as far back as 1886, France was considered a ”natural ally” of the Republic of Korea, an expression that takes on its full meeting in a context of continuing tensions with the north and international condemnation following North Korea's torpedoing of the Cheonan corvette in March.

While the French veterans of the French battalion were for a long time, through their association, a conduit of French influence and a foundation of Franco-Korean relations, this remembrance trail in tribute to France's participation in the Korean War, a gateway between the generations, will act as a beacon on the friendship between the two countries and the brotherhood of arms between the two armies. Tribute was paid to them once again in 2010 during the ceremonies held to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of war. In South Korea, the local and national authorities gave a very warm welcome in May 2010 (7) to those who fought for the Republic of Korea's liberty, while in Paris South Korean official and veterans had the distinguished honour of rekindling the flame of the unknown soldier.

Footnotes

(1) Former leader of the exiled government, he was elected president of South Korean in July 1948.

(2) Cf. Kim Yòng-myòng, Koch'yò ssùn Hanguk hyòndae chòngch'i-sa (Revised contemporary history of Korean politics), Seoul, 2001, p. 82.

(3) President of the Council.

(4) Minister of the Associated States (Union Française), formerly Minister of the Colonies.

(5) Opérations extérieures (overseas operations).

(6) Cf. François Léotard, Les casques bleus français, cinquante ans au service de la paix, in André Lavier, La France et l'ONU (1945-1995), Arléa, Condé-sur-noireau, 1995.

(7) The trip to South Korea organised jointly by the ANAAFF/ONU and the South Korean authorities took place in May.