Maurice Genevoix

Maurice Genevoix by himself

Maurice Genevoix was born on 29 November 1890 in Decize (Nièvre), a “little town straddling the Loire”.

His distant forebears were devout Swiss Catholics, who had fled the Calvinist repression, taking refuge in France. Hence their surname, Genevois (“native of Geneva”), the “s” later being replaced by the Limousine “x”. Maurice’s father, Gabriel Genevoix, the son and grandson of a chemist, was himself a business agent. He settled in Châteauneuf-sur-Loire shortly after marrying, and took over his sick father-in-law’s wholesale grocery business.

“My mother was twenty when I came into the world. It was in her arms that I drifted, a year later, to Châteauneuf. To drift [Genevoix uses the obscure French word valer, a sailor’s term], meaning to go with the flow, to entrust oneself to the current and, symbolically, to fate.”

He was to remain in Châteauneuf for many years. There, he and his younger brother, René, born in 1893, lived the happy, carefree years of true, eager childhood, “given to them completely”. Those years moulded his budding sensibility and introduced him, day after day, to “an eternally virgin, wondrous, endlessly blossoming world”.

“Life moved, for me, at the pace of childhood, making each day a small eternity.”

That “world” was also the world of the “Asile”, the nursery school he was sent to from the age of 22 months, followed by the “big school”, the village primary where he wore the cross that rewarded the good pupils – though that did not stop him from being a “hot-headed” child.

“We were impossible, due to sheer vitality. On my way back to school after lunch, long before I reached rue du Mouton I could hear, over the rooftops, the shouts of a hundred prepubescent voices. And I would start running.

All ‘pupils’, all in black aprons, all in it together, all equal before the secular prophets; and yet as different as their citizen parents.”

He would speak often of his family life in Châteauneuf, of his mother Camille, tender and cheerful, of the “shop” where he discovered the sounds and smells of life, and the three houses in which he lived.

“As my child’s personality was awakened, my own way of perceiving and feeling, I threw myself hungrily into the world that was offered to me. I discovered the street, the gardens, the people in their shops and workshops, the riverbanks too, the paved quaysides where the heavy mooring rings lay sleepily beneath the weeds and the rust, the tarred fishermen’s skiffs, the shoals of bleak turning over in the soapy swirl at the back of the wash house.”

“I consider it more than ever a great privilege to have spent my childhood in a little pre-war French town.”

But it would all change when, aged 11, he was sent away to boarding school in Orléans, 20 km away, for seven years.

“For the first time, I found myself enrolled: number 4. Life as a boarder at a French state lycée in the early years of this century was not unlike life in the army. All that is evoked by the word ‘barracks’, I experienced it there, aged 10, at Lycée Pothier, on rue Jeanne d’Arc, in Orléans: a cold, noble street, straight as a ruler, drawn rigorously taut between rue Royale and the cathedral of Sainte-Croix.”

He found consolation in his great liking for camaraderie, his talent for drawing and a love of reading, which opened up a whole other world to him. Jules Verne bored him, but he was full of enthusiasm for Hector Malot’s Sans famille, before immersing himself in London, Kipling, Daudet, Dumas and, above all, Balzac, who left him “flabbergasted. How shocking!” And he longed for only one thing: Sundays and the holidays, when he would regain his freedom and the warmth of family life.

But in 1903, at the age of 12, he lost his mother.

“On 14 March 1903, an early spring morning of indescribable magnificence, I was called to the headmaster’s office in the middle of class. He ‘prepared’ me, if I dare put it that way. Uncomfortable, certainly pitiable, he perhaps hesitated to deal me the blow outright. But from the very first moment, the look in his eyes and his faltering voice plunged me into the corrosive depths of despair, a gasping teenager suddenly faced with the hardest thing of all.

That teenager who, when the summer holidays came, wandered endlessly along the banks of the Loire found, in Châteauneuf, a house in darkness and a father overcome by grief, whose sadness, growing deeper by the day, caused him to make demands which a boy so close to childhood could not recognise or understand. The intense hunger for freedom which boarding school silently aroused in his subconscious drove him to an intolerance which the grieving man could not tolerate. So he fled, disappointing a call that refused to be expressed.”

“Since then... I know, I have learnt, it is a certain world order that has no use for the death of a young woman or a child. But I also know full well that my revolt was a man’s thing, that my refusal, beyond that closed grave, was what justified my own survival, my acceptance of the world, of the beauty of the dawn and the evening, the purity of the air we breathe, the children I myself would have. For how many years did I wake at night, my heart beating with joy, my ears still buzzing with the sound of a voice that had just called me, my hands warm from clutching my mother’s hands? My face was wet with tears, sweet tears, even after waking. Old man that I had become, I refound a young mother, smiling and tender; it was her, today once more, after the hardships of the years, who rekindled deep in my heart the invincible love for life that would only be extinguished with my death.”

Maurice Genevoix was a brilliant pupil, and his father decided he should continue his studies. “Early on, when I was 13 or 14, I was tormented by the need to express myself, to write.”

He left Orléans to do university preparatory classes at the Lycée Lakanal in Sceaux, “which had grounds where we could smoke pipes and a family of deer, penned in, just like us.”

Though not work-shy, he remained eager for freedom and, readily rebellious, jumped over the fence every morning to go and have a cup of coffee at the bar-tabac in Bourg-la-Reine.

In 1911, he was awarded a place at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure, on rue d’Ulm, in Paris, but decided to do his military service first. He was assigned to the 144th Infantry Regiment. Yet, contrary to what you might think, he did not find this year of “military servitude” a hardship.

“All in all, (...) compared to the servitude of the lycée, (it) left me with the memory of a happy liberation, dotted with comic episodes.”

He even refers enthusiastically to his period with the battalion of Joinville.

“Those weeks, that year, were definitely among the happiest of my life. Excitement, harmony, challenges set oneself, the simple daily happiness of discovering, with wonder, that the resources of one’s body were still equal to the bold behaviour of one’s youth.”

At the École Normale, between 1912 and 1914, he was a student of the director, the historian Ernest Lavisse, who, in 1916, would write the foreword to his first book, Sous Verdun (English title: ’Neath Verdun).

“The university, with its open forums, its free choices, its abundance, its contrasting individuals, was a continuation, on a different level, of the enchantments of my early youth.”

“The irony, the refusal to be taken in, the virtuosity of a critical mind put through unremitting training... The best of what I owe the (École) Normale, I owe to the normaliens.”

He owed it also to two men: Paul Dupuy, the École’s general secretary, with whom he was to exchange almost daily correspondence for thirty years, and Lucien Herr, the librarian, “who knew everything and gave everyone the key to what they were looking for.”

“Dupuy and Herr (…) remain, in my eyes, the guardians and examples of an oft forgotten, or little-known, humanity, whose decline or abandonment is not a credit to the times in which we live.”

In 1913, for his diploma of higher studies, he presented a noteworthy thesis on “Realism in Maupassant’s novels”, which appeared to promise him a brilliant university career.

“First in my year, I saw the avenues of an easy university career open up before me. I had already chosen from among them, at least virtually. I did not feel cut-out to be a high-school teacher. If I was to teach, it would have to be students close to my age. If I had an interest in arousing curiosity, I wanted to be free from constraint, without the worry of having to get through a syllabus in the year. For that reason, upon graduation, I intended to apply for posts at foreign universities.”

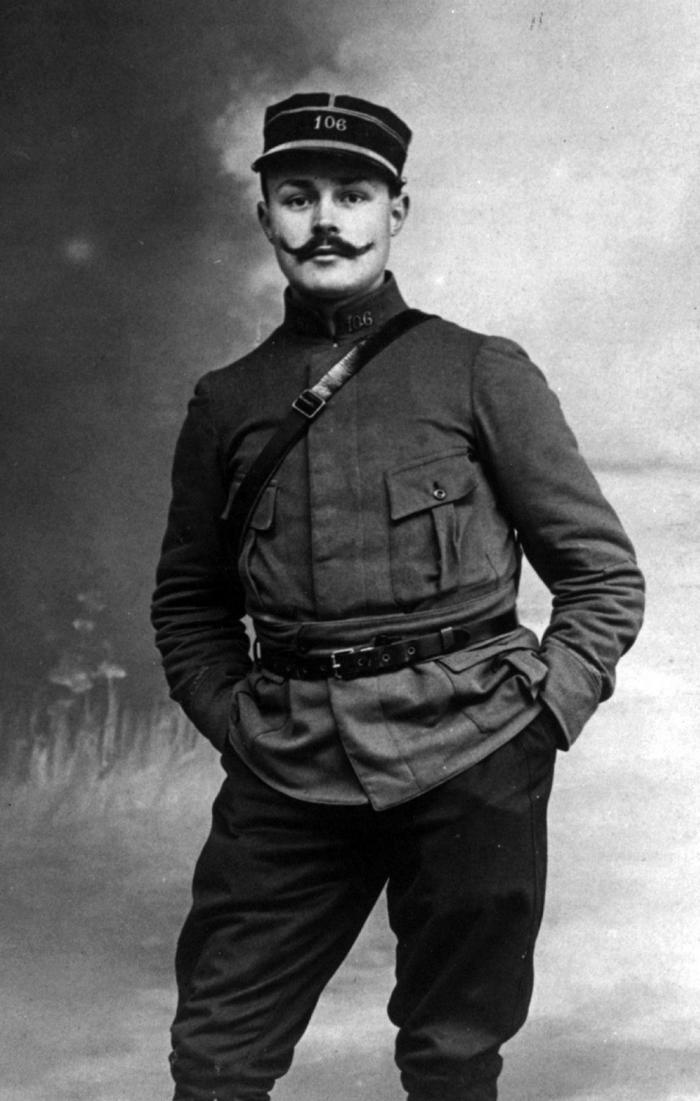

The outbreak of war prevented him from sitting his teaching examination. Mobilised on 2 August 1914, he joined the 106th Infantry Regiment, as a second lieutenant, in Châlons-sur-Marne. He left, with no flower in his rifle, saddened to the core, but at the same time “curious; intensely, entirely open and receptive, interested to the point of forgetting my apprehension and my fear.”

But within a few weeks, “this tremendous melee, which remained monstrously in human proportions”, plunged him into a world of blood, pain and horror.

“Everything, always: rain on the pallid back of a dead man, shells that bury and unearth, that roar, and howl with strange shrillness, giving out horrible, cheerful sniggers.

More and more frequently, as our fatigue grows, feverish images burst forth with the explosions: springing up, whole bodies in tatters; falling against the parapet, backs broken, like Legallais; headless, the head ripped off in one go, like Grandin’s, Ménasse’s, Libron’s, which rolled back to us from the neighbouring shell-hole in its brown woollen balaclava; scattering from mound to mound these sticky little things that you could reach out your hand and gather up; where do they come from, and what were their names? Desoigne? Duféal? Or Moline?

It scarcely leaves us now; we feel our chests squeezed, as if by an almost immobile hand. Against my shoulder, Bouaré’s shoulder starts trembling, gently, interminably, and somewhere a moan rises up from entrails of the earth, a regular groaning, a kind of soft, slow singing. Where is it? Who is it? There are men buried nearby. We search; it distracts us.”

He took part in the Battle of the Marne and the march on Verdun. After four months at Les Éparges, his battalion was sent to the “Calonne trench”, a strategic forest road the ran along the Hauts de Meuse hills. There, on 25 April 1915, he was hit by three bullets in the arm and chest, severing his humeral artery. He was evacuated to Verdun hospital, then on to Vittel, Dijon and Bourges. For him, the war was over. After seven months of treatment, he was discharged with 70% invalidity.

In August 1916, he returned to Paris, to work as a volunteer for the Franco-American Fatherless Children of France Society and, at Paul Dupuy’s invitation, lodged at the École Normale. But he rejected the suggestion put to him by the school’s new director, Gustave Lanson, to resume his studies with a view to sitting his teaching examination.

“Monsieur, we have changed a lot. In all ways, in fact. Morality, culture, justice, all that the word civilisation stood for we have had to call into question.”

Paul Dupuy had been encouraging him for months to write a book based on his memories of the war, which he had recorded in little notebooks. That book was to be Sous Verdun. Written in just a few weeks, with a foreword by Ernest Lavisse, it was published in 1916, heavily censored. That first book was followed by Nuits de guerre (1917), Au Seuil des Guitounes (1918), La Boue (1921) and Les Éparges (1923). All these titles received unanimous praise, and were subsequently brought out in a single volume, Ceux de 14.

Genevoix wrote these war memoirs at Châteauneuf. He had left Paris on doctor’s orders, having had Spanish flu. But what was prescribed to him had soon “become a free choice”. In Châteauneuf, with his father, he was “overjoyed” to rediscover his childhood haunts, where nothing had changed in his absence. Thus, after being a “war writer”, he went on to depict the region of the Loire, with a first novel, Rémi des Rauches (1922), about returning to civilian life and being reunited with the river, his world of light. It was nonetheless a continuation of his wartime writings.

“Rémi des Rauches is from 1922; I wrote it after La Boue and before Les Éparges (...) Yet although at no point does it evoke the war, or even mention it by name, it is still a war book.”

But the river was at once soothing and liberating, and from then on he would never stop celebrating it.

“It was the Loire. Mistress of all the passing hours, mirror of the moonlight and the star-filled nights, of the pink mists on April mornings, the thin clouds streaking the September sunsets, the long beams of sunlight piercing the summer clouds, she took that evening and, with each passing moment, carried it gently away, on her tranquil currents, into the night.”

In 1925, aged 35, Genevoix published Raboliot, which won the Prix Goncourt.

“What a fine book!” wrote the jury. “A fine book, filled with aromas, vigour, humanity... A simple, clear and lucid style, in which the slightest details are expressed exactly, the colour of the leaves, the shades of the horizon; the extreme precision of his eye, the perfect, succinct comparisons, in a word his admirable descriptive talent... The wonderful unity of the book, too, for, from beginning to end, the author goes straight to what he wants, what he feels: phrases at once fluid and energetic, rounded, shaped... Yes, it is a great book.”

To write it, he lived for weeks on a hunting ground bought by his uncle, “between Sauldre and Beuvron”.

“Adjoining a birch wood, surrounded by fish ponds and overlooking the lovely Clousioux lake, frequented by buzzards and herons, what could have been a better base for my writing projects than Trémeau’s gamekeeper’s cottage? I spent days there, nights too, with not an empty hour, not a dull moment: an osmosis between the land and me, the meadows of sedge, the sparse round oaks in the fine mist of the Beuvron, the yapping of a fox on a scent, the call of a bittern in the rushes, the breaking day, the first star, the leap of a carp, the gliding flight of a hunting buzzard.”

Yet he encountered no model for a poacher. Alone, or with the gamekeepers, he learnt to ring the bell, to do the rounds with the lantern, to lay the snares. A free man, he was against all forms of “regimentation” – a word he would use often – to the point of preferring rebels and dissenters. From Raboliot to the great red stag of La Dernière Harde (English title: The Last Hunt), his entire oeuvre extols freedom considered as a natural asset.

“The instinct of freedom (...) has always guided my choices like a good, reliable companion.”

During those years – 1925, 1926, 1927 – success, far from distancing Genevoix from the land of his birth, gave him the means to settle on the banks of the Loire, in a house to his liking. He found it by chance, one day in 1927, when strolling around Saint-Denis-de-l’Hôtel: a little country cottage, “abandoned by humans but peopled by birds and plants, which thrived there undisturbed.” It was called “Les Vernelles”. “I left the nests alone, those of the redstarts under the eaves, the blackbirds in the hedges, the lesser whitethroats in the bushy willows of the bank. From there, day after day for twenty years, I watched the sky change with the colours of the seasons, and listened to the bells of Jargeau answer those of Saint-Denis. I return there each year to see the wild strawberries ripen, until the time when the parasol mushrooms raise their hats beneath the acacias and the grass fires, smoking through the valley, announce the flight of the migratory birds.”

After the death of his father, who succumbed to a brief bout of pneumonia in July 1928, Genevoix decided to spend the rest of the summer at Les Vernelles. He stayed there with Angèle, who had been in the family’s service since 1898. With them they took a cat, who was so taken with the charms of Les Vernelles that, when they returned to Châteauneuf in September, it made its own way back to Saint-Denis-de-l’Hôtel. From this domestic anecdote, Genevoix was to make a novel, Rroû (1931), recently reprinted with a foreword by Anne Wiasensky. The book, together with La Boîte à pêche (1926; English title: The Fishing Box), marked the beginning of a particular kind of production by Maurice Genevoix: his romans-poèmes, or “novel-poems”. These included Forêt voisine (1933), La Dernière Harde (1938), Routes de l’aventure (1959) and Bestiaires (Tendre bestiaire and Bestiaire enchanté in 1969, Bestiaire sans oubli in 1971), much of them written at Les Vernelles.

In early 1939, two months after the death of his first wife, he left Les Vernelles on a trip to Canada, where he gave a series of conferences over several months. He was to stay there until the eve of the war. The lover of the banks of the Loire was not looking for a change of scene on this trip, but rather to find “harmony within himself”. Upon his return to France, he published his travel notes (Canada, 1943) and went on to devote a number of books to that country: first, a collection of short stories, Laframboise et Bellehumeur (1942), then a novel, Eva Charlebois (1944). Canada was present, too, in Les Routes de l’Aventure (1959) and in his children’s short stories, L’hirondelle qui fit le printemps (1941) and L’Ecureuil du Bois-Bourru (1947).

“Of all the countries I have been on my travels, Canada appealed to me the most (...). It presented me with themes which of their own accord were in harmony with my inner world.”

In 1940, he left Les Vernelles for the Free Zone and spent the next two years in a village in Aveyron. There he wrote La Motte rouge (1946), a grim novel about intolerance and the Wars of Religion, which cannot be read without the key of the Occupation, as suggested in its epigraph: “It was a wretched and devastating time.”

He also wrote a “journal of humiliating times” there, which disappeared in the turmoil and was only recovered much later. There he met his second wife, Suzanne Neyrolles, a widow herself and mother of a little girl, Françoise.

After the invasion of the southern zone by the Germans, the three of them returned to Les Vernelles. But the house had been ransacked. He thought of selling it, but Suzanne set about restoring it to its former glory. Their daughter, Sylvie, was born there on 17 May 1944.

“She would laugh and lift her eyes to me, to witness her joy, entirely accepting of the world, its wonders and their miraculous inrush. What is love if it does not share, does not accept what it receives with the same movement with which it offers and gives?”

The war over, he resumed his travels and conference tours, which this time took him to Europe, the United States, Mexico and Africa (Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Senegal, Mauritania, Guinea, Nigeria). After Canada, Africa sparked his creative imagination. Afrique blanche, Afrique noire, a book of travel impressions, was published in 1949 and the novel Fatou Cissé, also inspired by Africa, in 1954.

He was attentive to the wide-ranging problems faced by these countries, including their political aspects. But for him, travel was above all an opportunity to discover a diversity of landscapes and customs and, beyond that, to recognise different ways of living, being and thinking, which he described as universal.

“I approached other cultures, perceived their genuine warmth and felt stir within me a feeling of human brotherhood, which had been awakened by my travels among real men.”

Elected to the Académie Française in 1946, to the seat of Joseph de Pesquidoux, he was invested on 13 November 1947, by André Chaumeix.

“One never enters here alone... For men of my age, there are, among the dead, those who have kept, and will keep forever, the face of youth. Of those young war dead, we, in our own youth and our mature years, have been painfully deprived.”

“I regard as a moving privilege that I was lucky enough to freely encounter, over a third of a century, men so wholly and diversely men as most of my colleagues. I have greatly admired many of them, respected them all and formed friendships with some which are the pride of my life.”

In October 1958, he became Perpetual Secretary. He dusted down the venerable institution, set it up with great literary prizes and worked to enable the election of Paul Morand, Julien Green, Montherlant, etc.

He also made sure the Académie played an active role in all the bodies responsible for the defence of the French language. Under his leadership, it asserted its presence and competence within the High Commission for the French Language, founded in 1966, and the International Council for the French Language.

He would go to Les Vernelles as often as possible, to spend “days on (his) personal work”, but he now had to limit himself to shorter works. Among his short stories for children, Le Roman de Renard (1958; English title: The Story of Reynard) playfully made “the beasts talk” but, as a literary metaphor, it was also an ode to freedom.

“It is a tough, unending struggle for those wishing to safeguard their freedom this century.”

He published a number of autobiographical writings too: Au Cadran de mon clocher (1960) and Jeux de Glaces (1961). He also rediscovered “the myths that drove (his) creativity”: the river, with La Loire, Agnès et les garçons, a novel he described as a transposition into adolescence of Jardin dans l’île, written much earlier, in 1936; the forest, with La Forêt perdue (1967);

finally, with La Mort de près (1972) he took up his wartime memories once again.

“Around my 25th year, circumstances would have it that I should experience death, three times, at very close quarters. Put very precisely: to experience my own death, and survive. This memory has pursued me constantly, like weft entwining the warp of my days.

I should add that it has helped me, and continues to do so, that I know, I am certain, and that certainty determines my current attempt: storytelling is a means of transmission, like the guardian of a message which ought to be beneficial.”

For a radio programme on France Culture, he wrote a series of animal stories that went on to be published as the collection Tendre Bestiaire (1968), soon followed by Le Bestiaire enchanté (1969) and Bestiaire sans oubli (1971).

But the work associated with his duties was too much of a burden on his freedom. In 1974, he did what no other Perpetual Secretary had done before him: he resigned.

On 9 October 197?, Joseph Kessel wrote to him: “I learnt rather belatedly of your decision. I know... I know... You have done the right thing. You have given us much and for a long time. And I am happy that you have your freedom once more. But from a selfish point of view, it is a blow. You were the bond, the element of friendship. You humanised the role so wonderfully. ”

Maurice Genevoix would recount the pleasures, obligations and occasional disappointments of his position in a short work entitled La Perpétuité (1974).

“The centuries-old Académie is not short of perpetuals. It has the centuries on its side. It is wise and magnanimous. It will not hold it against me, writer that I am and mindful – as we all are, even those who claim not to be – of leaving behind me the hint of a wake in the shoreless ocean of time, that I changed perpetuity.”

He returned to Les Vernelles, where, “time after time”, no matter what path he trod, he would always return.

“It was my house, my garden, my land, all I had ever needed in my life.”

There he wrote Un jour (1976), a novel he had been mulling over for some time, which is also a philosophical text: “That of a day like any other, like yesterday, like tomorrow, in which love and death, war, devotion and friendship, storms and calmer weather all come to pass, a weird and wonderful tale perhaps, that carries us over the infinite planet where we are, but where the beauty of things is only what it is if it is divine, beneath a sky whose immensity raises the invincible hope of men.”

With this book, which was a great success, he found his loyal readers once again. It was followed by Lorelei (1978), a novel of teenage confrontation, in which a German boy and a French boy, with their different temperaments, are torn between hate and friendship.

His last book, Trente Mille Jours (1980) – 30 000 days of memories since his childhood in Châteauneuf – established him, together with television, as a household name. The general public rediscovered the storyteller, the Loire wanderer, the passionate ecologist even before the term existed, the lover of language who spoke such pure French, a witness of his century and an ardent defender of his heritage. People fell for his charm, his culture without pedantry, his attention to others, his ability to capture the human in every man.

“Life went on, the life of a man among men, with his share of sorrows and joys; and, year after year, always engaged. I am one of those who have never been tempted, save during my months at the front (...), to keep a private journal. What’s the use, if there is not a page of what they write and publish where they are not entirely – as I’ve just said – engaged? What begins as a barely audible call, a temptation besieged by anxiety, is gradually revealed to be an inner force which, by a fatal sequence of events, little by little makes a vocation into a way of life, or life into a vocation. That is just how I experienced it, how I have always written.”

He still had other projects, a collection of “Spanish short stories” and also a “possible book” that would once more address “childhood and initiation”. But he died suddenly on holiday in Javea, Spain, on 8 September 1980, shortly before his 90th birthday.

“Fortunately, memory is selective. It knows the dead it is dealing with, it lives off them as much as it does off the living.. There is no such thing as death.. I can close my eyes; I shall have my heaven in the hearts of those who remember me.”