Remembering the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71)

The 150th anniversary of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) shed new light on a conflict which many believed had been forgotten by French and German national memory. As well as involving voluntary, cultural and remembrance organisations, it provided an opportunity to look at the traces of that memory, on both sides of the Rhine, and the mark it has left, still today, on the territories concerned.

2020 was the 150th anniversary of “the forgotten war” – the epithet commonly attached to the Franco-German conflict of 1870-71. A vox pop would soon show there is good reason for describing it that way. Our contemporaries in both France and Germany know next to nothing about the subject, other than that for some it means the birth of the Third Republic, for others a time of national unity; for still others, it concerns a rivalry that was one of the causes of two world wars. How can such a decisive event be “forgotten”? The many commemorations, exhibitions, publications, conferences and colloquia held throughout 2020 and early 2021 show that “the forgotten war” has not really been “forgotten”, or that we need to define the term. Aside from the widespread ignorance of a population which cannot have forgotten what it never learnt in the first place, what traces did the Franco-Prussian War leave on either side of the Rhine?

Memorials to German soldiers killed in the Franco-Prussian War, at Ehrenthal, near Saarbrücken.

Fighting of 6 August 1870. © Léon & Lévy/Roger-Viollet

A memory etched in the landscape

Two points make for a clear differentiation: the fate of each country – one victorious, one defeated; and where the conflict took place – in France. The Franco-Prussian War is necessarily a positive memory for one side and a negative memory for the other. On one side is the pride of a victory as swift as it was flattering; on the other, the trauma of defeat, destruction and the suffering of civilian victims, added to the loss of those who “died for their country”. Yet this initial opposition caused the same, new suffering. On both sides of the border, this first war involving conscription hit the people hard, unaccustomed as they were to such high death tolls: 139 000 French and 51 000 Germans. The awareness of this collective tragedy explains Article 16 of the Treaty of Frankfurt, requiring the two governments to “maintain the graves of soldiers buried on their respective territories” – French graves in annexed Alsace and Moselle, German graves on French soil, and also the graves of French prisoners who died in captivity.

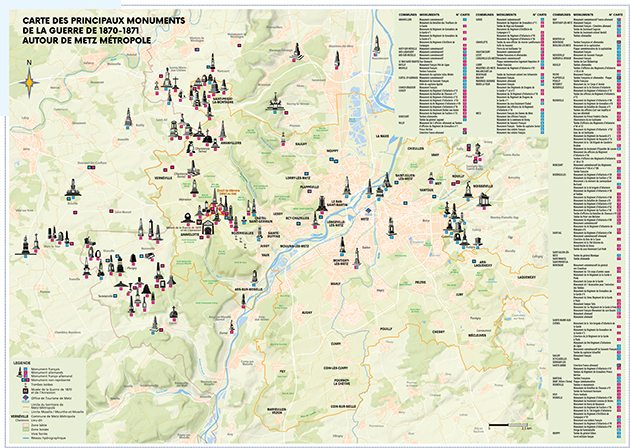

Map of the principal Franco-Prussian War memorials around Metz. © Metz métropole

This concern with honouring the memory of military casualties was unprecedented, and came to the fore as soon as the war was over. Funded to begin with by communes, churches, local groups or regimental friends’ associations, then by central government and organisations like Le Souvenir Français, memorials were erected on the sites of the key battles and in town and city squares. For a long time, they etched the memory of the Franco-Prussian War into the landscape. A number of these monuments have disappeared, taken down in 1919 by the French, like the Friedrich III monument in Woerth, destroyed by bombing or melted down during the German occupation (1941-44); they have also been supplanted in importance by memorials to the victims of the world wars. The monuments were catalogued at the time of the 150th anniversary, however, and were found to include more than 800 plaques, graves or specific memorials in France, across all departments. A map of Franco-Prussian War memorials published by Metz district council shows 167 remembrance sites in the Metz area alone. On the battlefield of Woerth-Froeschwiller alone, walkers come across at least 84 references to the French and German soldiers killed in the sector. These are only examples for the purposes of remembrance tourism, which received a boost from the 2020-21 commemorations. But making information available like this shows a healthy concern that visitors should not be allowed to forget – including German tourists, who come to the area in their droves.

A Franco-German ceremony in remembrance of the Franco-Prussian War, in Gravelotte, attended by the French Minister for Remembrance and Veterans, Geneviève Darrieussecq, and Minister Plenipotentiary of the German Embassy, Pascal Hector, 30 August 2020.

© Erwan Rabot/SGA-COM

Memorials are an important remembrance resource. But the efforts involved in restoring the more damaged among them, and equipping them with suitable signs for tourists, are proportional to how “forgotten” the conflict has become. We must also understand the reasons for this situation, which is not due to a desire for concealment or indifference. The “forgotten” memory of the Franco-Prussian War must be understood with reference to the events that have reshaped Franco-German relations since 1919.

A desire to “erase” the memory on both sides of the Rhine

In France, an active process of resilience initially turned the memory of the defeated to their own advantage. Antonin Mercié’s Gloria Victis (1874), adopted by many towns and cities across France, is its most emblematic expression: a work that prompted the creation of others, which remain very much a presence in public places today. Elected “France’s Favourite Monument” in 2020, Frédéric Bartholdi’s Lion of Belfort (60 000 visitors in 2018) and its replica in Place Denfert-Rochereau, Paris, are living proof of this heritage remembrance easily accessible to French people’s curiosity. Their ignorance of the history they represent is regrettable, but there is a reason for it: with the return of Alsace-Lorraine to the bosom of the motherland, in reparation for the damage caused by the Franco-Prussian War, the French people no longer had any reason to be bound by the duty of remembrance which they had fulfilled up until then. For them, the matter was closed and the cruel resurgence in 1940 did not prompt any lasting change. After 1945, the Franco-Prussian War practically vanished from secondary-school syllabuses.

In Germany, it was similarly erased after 1919, but for a completely different reason. “What was created by a victory is swept aside by a defeat,” wrote François Roth. The humiliation of the Diktat pushed the positive memory of 1871 into the background. This was made all the easier since neither Sedantag (2 September) nor the anniversary of the birth of the Reich (18 January) had ever had truly unanimous support in Germany. They were too Prussian for many Germans’ liking. The Bavarians, for instance, remained more attached to the memory of Reichshoffen (6 August) than Sedan. The proclamation of the Third Reich might have renewed the bonds of continuity with the pre-1914 Prussian military monarchy. But the Diktat, and the subsequent Hitler regime, combined to banish the Franco-Prussian War from German memory. In many towns and cities across Germany, streets still bear the names of the battles of Metz, Wörth or Belfort, but residents no longer associate them with the Franco-Prussian War. Such ignorance is rivalled in France only by such street names as rues Adèle Riton in Strasbourg, Général Renault or de la Petite Pierre in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, Juliette Dodu in Montreuil, or Faidherbe in Lille; or traditional songs like Les cuirassiers de Reichshoffen. French culture is still imbued with all these traces – the memory that remains when the main substance has been forgotten or else never explained. It is found in expressions still in common usage today, including by people who are ignorant of their original meaning, such as “a bottle the Prussians won’t get their hands on”, something that “falls like at Gravelotte” or “gaiter buttons” (meaning every detail is ready).

The Cold War and European integration reinforced the joint desire on either side of the Rhine to keep the memory of the Franco-Prussian War “in the closet”. The border to be defended shifted east. Against the Soviet threat, French and West Germans sought unity (1957 Treaty of Rome) and reconciliation (1963 Treaty of Paris). From then on, if it was still necessary to remember the Franco-Prussian War, it was no longer to accomplish or counter an act of revenge, but to build the United States of Europe which Victor Hugo had dreamed of since 1849 and about which he had reminded the Germans on 9 September 1870, hoping they would put an end to the war. In this spirit, in 1970, the centenary was marked by many joint events and the issue of three French stamps, one of which emphasised peace, while the other two portrayed the Lion of Belfort and Gambetta’s balloon, both powerful symbols yet which did not foster hatred of the former enemy. When it is forward-looking rather than only honouring those who have given their lives for the wider community, remembrance chooses in the past what will drive its future. After 1945, the Franco-Prussian War was not forgotten; its memory was just put on the library shelf, accessible to anyone with the curiosity to look.

The vivacity of local remembrance

This calculated “amnesia” did not prevent local remembrance from remaining very much alive. In Paris, although the image of the siege and the exotic menus served during it has to some extent survived, aside from one conference 2020 did not give rise to major commemorations. The capital’s identity was not well suited to it. One had to head for the suburbs – Sucy-en-Brie, Bry, Champigny or Villiers-sur-Marne – to find exhibitions, talks and other activities. At Bry-sur-Marne, for instance, the anniversary was marked by the restoration of the commemorative plaque at the church of Saint-Gervais - Saint-Protais, and the burial in the military plot of a French soldier killed 150 years earlier. But remembrance of the Franco-Prussian War is stronger in the provinces, particularly in the east: in Belfort and Bitche, the citadels that held out; in Sedan; and in Bazeille, where remembrance centres every year on the marine troops who distinguished themselves. Even so, with Loigny-la-Bataille and Châteaudun, the departments of the west are not far behind. This local vitality was further seen in Savines-le-Lac (Hautes-Alpes), where a monument was unveiled to honour the memory of the Savinois who returned from Argentina to defend their homeland. The memory of 1870 remains very much alive.

Bartholdi’s Lion of Belfort. © Rights reserved

As part of their programmes to promote tourism, regions and communes also have many initiatives in place. To cater for demand, museums have been renovated (Woerth in 2017), while in Gravelotte, the Musée de la Guerre de 1870 et de l’Annexion opened in 2014. At many sites, local history associations are very active. They receive the support of their German counterparts, who come to the sites every year to remember their dead, maintain the memorials and thus participate in the remembrance dynamic. In 2011, the German lions monument in Wissembourg was restored through the joint efforts of the residents of Wissembourg, Woerth and the Weißenburger Land in Bavaria. To mark the 150th anniversary, the French Ministry of the Armed Forces, in association with Le Souvenir Français – an organisation set up in 1887 to preserve the memory of the war and its dead – held a commemorative ceremony at Gravelotte (30 August 2020). Alongside the French Minister for Remembrance and Veterans, Geneviève Darrieussecq, the Minister Plenipotentiary of the German Embassy, Pascal Hector – who was also invited to the Battle of Loigny commemoration in December – spoke at the event. From the outset, he emphasised his desire to “celebrate the deep friendship which today unites our two peoples” and expressed his wish to jointly commemorate their history, which he deemed “all the more necessary as each new generation must learn to distinguish the idea of the nation from nationalist ideology. It is therefore of the utmost importance to involve young people in this remembrance.”

All these activities, events and programmes geared to education as much as tourism are the mark of shared remembrance, the expression of the awareness of a common history which now unites those it previously opposed. Today, on either side of a border which is no longer a dividing line but one of free movement, there lives on a memory of the Franco-Prussian War that no longer sees one side awaiting revenge and the other living in fear. Thus reconfigured, remembrance of the Franco-Prussian War reminds us how much of war is about shared suffering, which we would do well to keep to a minimum.