New Caledonia in the two World Wars

As was the case for all of France and the French Empire, New Caledonia, one of France's principal possessions in the Pacific, played a role that remains mostly unknown in France today but was nonetheless important, or even crucial, at certain points during the World Wars, especially in the Pacific operations during World War II.

I - New Caledonia and the Great War

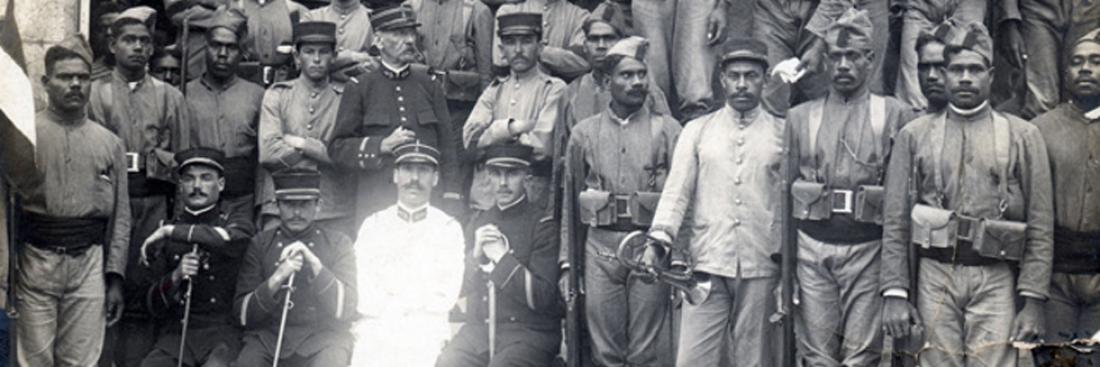

Noumea, departure for La Grange, 4 June 1916 © Noumea City Museum

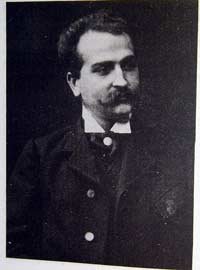

From the point of view of the contingents involved, according to the official French statistics, one thousand fighters came from Oceania. Moreover, for the needs of the war, the Kanak people were called upon, notably with the help of a Protestant pastor (the Protestant religion was imported by British explorers and colonists in the 19th century and is very important), Maurice Leenhardt, who took on the role of a mediator and spokesman for ”mobilising” the Kanak populations. The argument developed was quite traditional. The Kanaks' participation in the fight earned them France's recognition, ensuring them good land and the means to cultivate it.

Maurice Leenhardt in 1902. Source: DR

Thus, the first convoy of 700 Melanesian soldiers left Noumea on 23 April 1915 on the Sontay, after several weeks of training for the recruits.

The Sontay embarks troops at Noumea, 23 April 1915. Source: P. Ramona Collection

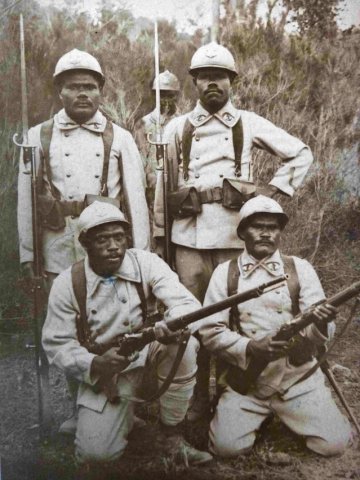

According to the archives of the Amicale des Anciens Combattants de Nouvelle-Calédonie (New Caledonia Veterans Association), out of 1,134 Melanesian volunteers who went to France between 1914 and 1918 (or approximately 18% of the men of fighting age), 374 were killed on the front, notably in the Aisne in July-August 1918, and 167 were wounded. Furthermore, of the 2,290 men of the Bataillon du Pacifique (which, of course, included recruits from all French possessions), 332 were decorated on the front.

Kanak Tirailleurs, undated. © Noumea City Museum

II - New Caledonia and World War II

Thus, the Governor of New Caledonia, Mr Pélicier, decided on 20 June 1940, to ”continue the fight alongside the English”. A few days later, as the Governor started to hesitate, the Privy Council, a consultative body comprising four civilians and two civil servants, and the General Council, a deliberative assembly with four elected members, maintained the position that the fight should go on. It should be pointed out that this position was not unique, as many personalities around the Empire expressed the same desire despite the armistice.

Michel Verges. Source: Museum of the Order of the Liberation

While Governor Pélicier was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Denis and part of the African colonies joined Free France from the Pacific Establishments in the night of 18 to 19 September 1940, hundreds of residents of the bush ”descended” upon Noumea to demand that they rally General de Gaulle, while on 19 September, Governor Henri Sautot arrived in New Caledonia from the New Hebrides as General de Gaulle's representative. At the end of the day, the new Governor announced to the population that they had rallied de Gaulle.

Governor Henri Sautot. Source: Museum of the Order of the Liberation

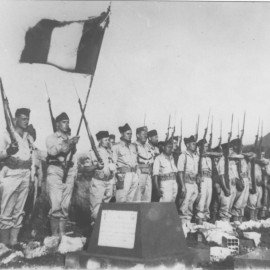

On 3 May 1941, during a ceremony at the war memorial in Noumea, the Bataillon du Pacifique was created, its flag being handed over to Captain Félix Broche. As of April 1941, 605 volunteers, 287 of them Caledonians, signed up to form the battalion which also included recruits from Tahiti and the New Hebrides.

Capitan Félix Broche. Source: Museum of the Order of the Liberation

Arrival of the Free French Forces on the English lines. Source: Imperial War Museum. DR.

San Giorgio Cemetery: before leaving Italy. The BIMP salutes the flag along with the delegations from all the Companies forming a Section, to those who would never return to France. Source: Amicale de la 1re Division Française Libre. Polvet Collection.

April 1945, BIPM parade in Nice. Source: Museum of the Order of the Liberation

Flag. Source: Amicale de la 1re Division Française Libre.

From 1942 to 1945, New Caledonia was also an essential support base and a key location for the American and Allied troops during the Pacific War, notably contributing to strategic deployment and logistics support during the re-conquest carried out by the American forces against Japan. Indeed, on 12 March 1942, an American Expeditionary Force landed in Noumea under the orders of General Pach. Despite the difficult relations with the new governor, Admiral Thierry d'Argenlieu, the American, Australian and New Zealander allies were to make full use of New Caledonia as a highly effective ”aircraft carrier” against the Japanese, notably during the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942.

Georges Thierry d'Argenlieu (right), governor of New Caledonia in the name of Free France, with Brigadier General Alexander Patch, commander of the American Poppy Force, in Noumea. Source: U.S. Federal Government