Reporters of war

Contents

Summary

DATE: February (1) and May (2) 1915

PLACE: France

OUTCOME: Establishment of the army cinematographic unit (1) and the army photographic unit (2)

During the Great War, the only pictures sent back from the front were those taken by military photographers. Civilian photographers were not permitted to cover the events as they unfolded. One hundred years later, alongside civilian reporters, enlisted reporters continue to document...

For more than a century, army photographers and cameramen (and operators) have produced a record—employing the technical equipment available to them and toeing the ministerial line—of the conflicts that affected their contemporaries at the time and continue to affect society today. Their news images broadcast through every media channel, from the written press to the Internet, have depicted the course of our modern history and kept the memory of our dedicated troops alive. While the French military authorities knew the benefits of photography since the technology first appeared in the 1830s, they did not immediately jump on it as a means of representing the strategy and supporting the instruction of troops. In 1895, the Lumière brothers patented the Cinématographe, a combination film camera and projector.

In 1915, the French army engaged in the First World War established, as did the German army, two units dedicated to taking still and moving images of its operations: the army photography unit and the army cinematographic unit. From that point on, the military authorities profited from these technological innovations to take and produce, in times of war as well as of peace, photographs and films that helped relay their message and document their history.

Banned image: German prisoner amongst the infantrymen, at "La Fauvette", Talou region in Meuse, 20 August 1917.

© Albert Samama-Chikli / ECPAD / Défense

ON THE FRONT OF THE GREAT WAR

In May 1915, four French ministries—the War, Foreign Affairs, National Education and Fine Arts ministries—joined forces to create the Army Photography Unit or Section photographique des armées (SPA) following the enemy’s example. The photographers were a mix of conscripted civilians who worked for photography companies affiliated with the national photography trade association and servicemen. The Army Cinematography Unit or Section cinématographique des armées (SCA), established at the same time, was run by four major French production companies involved in producing newsreels: Gaumont, Pathé, Éclair and Éclipse.

In 1917, the French War Ministry turned producer and sole distributor after both units were merged into one and named the Army Photography and Cinematography Unit (SPCA). Its mission was threefold: to produce images for the purpose of propaganda, primarily through newsreels; build up the historical archives, and create content for the military archives. At the front, photographers and cameramen worked in concert. Their actions were under rigorous supervision. They were only permitted to travel by order of the War Ministry or the French army general headquarters and were always chaperoned by a staff officer. It would be the operator’s responsibility to transport with him the photographic or film camera, tripod, and cellulose nitrate reels or glass plates. The filming conditions and strict supervision somewhat encumbered by heavy equipment meant that the unit primarily ‘shot’ the battle adjacent: the ferrying of the troops or artillery, the wounded, the prisoners and the camps. Images of the front and the injured were not shown until after the French victory.

Germaine Kanova, SCA photographer, carrying a Rolleiflex, Bade-Würtemberg, 11 April 1945

© ECPAD/Défense

At the start of the war, the equipment was supplied by civilian production companies and later the cameras were hired. Each operator would send his negatives to the production company he worked for, which would then develop and print the films. The prints would be mounted and annotated on boards and the photographs captioned before being presented to the military censorship commission. Any photos or footage of the dead or wounded, frequently taken by camera operators such as Pierre Machard and Albert Samama-Chikli, were prohibited by the censorship commission lest they weaken national morale. Photographers and cameramen in the SPCA were interested in every aspect of the Great War. However, the distribution of their images was strictly regulated. While not every image was destined for public distribution, all photography and footage had to be archived. Censorship was exercised at the point of distribution.

During the interwar period, and at the time of the Spanish Civil War in particular, the war reporter, such as Robert Capa or Gerda Taro, became a familiar figure in civilian life. At a time when the illustrated press was growing in popularity, the political impact of published photos became sensitive to public opinion. Conscious of this shift and helped by the technical development of cameras, which became lighter and more easily transportable, photojournalists sought to get as close to the action as they could. However, exposure to risk was just as prevalent, especially owing to their restricted field of view when looking through the lens. Nevertheless, risking their life to capture images was an occupational hazard they willingly accepted. In 1937, Gerda Taro was crushed to death by a tank.

“UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL WITH TROOPS”

Conscious of the stakes at play in managing photographs and film footage, the warring parties engaged in the Second World War employed both media as an implacable psychological weapon serving a cleverly orchestrated propaganda campaign in support of the war effort. On the French side, the co-existence of two governments each claiming legitimacy was reflected in the management of images. Official teams of photographers and cameramen were active in Vichy (attached to the General Commission for Information) as well as in London and Algiers (with the Office of Information through Cinema). From 1944, in mainland France, other operators accompanied the liberating forces and witnessed first hand the horrors of war. Indeed, Germaine Kanova took photographs endowed with realism and a profound humanism, emphasising the dignity of men scarred by an environment devastated by years of war. Jacques Belin, meanwhile, observed attacks by the troops, and captured the energy of battle and immortalised the soldiers.

When the Second World War broke out, army reporters wanted to be as close to the troops as possible. In the post-war period, in mainland France, the photography and cinematography units had a hand in building the identity of the country’s national defence. At the same time, reporters were sent to Indochina to garner public support for a far-flung conflict. Their main mission was to show the face of the enemy. Yet these directives put reporters in tough circumstances. For instance, Paul Corcuff who after enlisting in June 1944 was sent to Indochina in 1949 to observe the military operations at close range, accompanying the withdrawals, and experiencing the living conditions and general feelings of exhaustion. From the inside, he witnessed the daily reality of the fighting forces but was appointed by the Press Information Service (SPI), a unit attached to the army’s department of propaganda. Army photographer Pierre Ferrari also wanted to be as close as possible to his subject. In the heat of action his images neither elude war nor death.

Soldiers of the 1st RBFM (Armoured Marine Regiment) and 2nd DB (Armoured Division) aboard a jeep during the liberation of Strasbourg near the Montafgne Verte rail bridge, November 1944.

© Jacques Belin/Roland Lennad/ECPAD/Défense

However, neither photographer had any power over the future of their images, which were subject to the obligatory information controls before they were published in the international press. This way of working—which would become the accepted standard of many photographers including Henri Huet during the Vietnam War—was exacerbated by the necessity to employ equipment (such as the Rolleiflex 6x6) that was cumbersome and poorly suited to the subjects in hand. The Arriflex used by Pierre Schoendoerffer and already the motion picture camera of choice of cameramen during the Second World War had only three minutes of battery life and took very short reels. The camera operator was obliged to carry around equipment including chargers, films and spare batteries, weighing in at over 20 kilos. Transporting such a heavy load, operators were unable to film at will, instead forced to capture short albeit well planned shots that today are some of the most iconic images of the conflict (parachutists, Diên Biên Phu and so forth).

The photographs taken by army reporters depicted the reality of the battlefield. But the editorial choice had to dovetail with a communications strategy that extended outside the French borders. The images of military operations in Indochina had to specifically meet the communications objectives defined by the French government within a tense international context. While civilian reporters were less beholden to the imperatives of political communications, military reporters, some of whom were veterans, could more easily integrate into the forces.

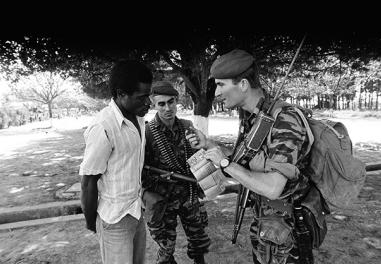

After Indochina, the French army was deployed to Algeria. During this conflict, the French Ministry of Defence deliberately avoided sharing any images of large-scale military action. In the field, the General Government of Algeria set about developing its local action, such as distributing tracts and installing loud speakers (under the orders of the 5th Bureau of Psychological Warfare). The SCA unit stationed in Algiers was organised and scaled up to meet the growing demand for news images. The unit enjoyed an almost exclusive monopoly in terms of producing “operational” images to be sent out to press organisations and the military. These images were chiefly images of captured prisoners or psychological warfare operations led by the 5th Bureau against the civilian population. At this time, one photographer who adopted an alternative approach emerged: Marc Flament, a photographer appointed by Lieutenant Colonel Bigeard. He took part in all the operations conducted by the men of the 3rd Colonial Parachutists Regiment (RPC) and immortalised the parachutists and commandos in aestheticised shots that showed the soldiers as heroes. His images, which were shot outside the regulatory confines of the 5th Bureau and the filter of institutional censorship, reflected the harsh realities of war.

THE ERA OF OVERSEAS OPERATIONS

Deployed principally to produce instructional and informational films from a more institutional angle, military reporters followed armies in peace time but also during periods of international conflict. Indeed, during the 1970s and 1980s, the teams of reporters employed by the Army Photography and Cinematography Establishment (ECPA) took part in overseas operations in Kolwezi, Lebanon and Chad. The French army was then a participant in international operations and it was not long before its deployments would be exclusively under the mandate of the UN or NATO.

Photographer Marc Flament, Algeria.

© Arthur Smet/ECPAD Collection Smet

Photographic and audiovisual equipment was improving all the time. This meant reporters could work more autonomously and move around more easily. Reporters worked with several cameras, which might be colour or black and white. From the 1980s, army reporters enjoyed a certain amount of freedom, such as François-Xavier Roch who immortalised far more than just the action of the French army in Lebanon and started a career as a photojournalist. However, as soldiers first and foremost, army reporters undoubtedly tended towards self-censorship, which was likely guided by a sense of propriety among brothers in arms. Pierre Schoendoerffer, for example, always refused to film a soldier in agony. Similarly, during the attack on the Drakkar barracks in Beirut on 23 October 1983, killing 58 French parachutists, Joël Brun, the ECPA photographer stationed there, refused to film the first hours of the dramatic scenes but waited until the next day to photograph the searches and act on behalf of the forensic identification team, documenting the identity of the victims and the collection of the ID tags. Consequently, he did not capture the initial explosion or the terror on the servicepeople’s faces.

During the 1970s and 1980s, photographers and cinematographers had to send their reels and films to the head quarters based at the Fort d’Ivry to be developed. This somewhat delay their publication. In the 1990s, the use of satellites to transmit analogue video images via Inmarsat revolutionised practices. During the Gulf War, camera operators sent their footage of warfare and the Allied breakthroughs in Saudi Arabia and Iraq directly. This development allowed for rapid broadcasting on TV following authorisation by the military command. In subsequent years, this system of transmission remained expensive and heavy (around 10 kilos) but did allow operators in the French army to document, almost instantly, the action of the French armed forced in combats or in contact with civilian populations in Rwanda, former Yugoslavia and Kosovo, through news items covered to rally French support. Until the 2000s, operators would even entrust their films to those able to transport them back to France, such as pilots.

From the start of the new millennium, digital technology began to replace analogue technology. ECPAD, the French delegation for defence information and communication (DICoD), and the Army Information and Public Relations Services (SIRPA) deployed to the field photographers, camera operators and sound recorders as well as journalists (civilian and military) who had the capability to publish their work almost instantly, after authorisation by the army military command, and to produce written press reports for army publications or for external use (TV media, for example).

In the field, however, technology was not the only constraint. Photographers and camera operators might have orders to follow and objectives given by the military communications advisor in the field. The photos or footage they produced was then contingent on the decisions of the communications officers. In Côte d’Ivoire between 2003 and 2005, they produced less archive images than evidentiary images and news images.

Paul Corcuff, photographer for the SPI, with his Rolleiflex hanging from his neck, during Operation Mouette in Indochina, 23 October 1953.

© ECPAD/Défense

Framing a precise and restricted subject gives the impression there is no reverse angle for the troops, but also makes it possible to produce images endowed with certain characteristics: the camera is closer to the troops, in particular at moments which are rarely captured on film by civilian journalists. The images thus become weapons in the hands of both parties, especially in the case of asymmetrical warfare. Operators in this situation form a Combat Camera Team.

“COMBATANTS IN THEIR OWN RIGHT”

The 2000s also beckoned in a change in how subjects were treated. In Afghanistan, for example, photographers and videographers recorded the main missions to which the French army was deployed. However, the prisoners and dead of the enemy were never photographed to ensure the material was never used for the purpose of propaganda. The French army took with them journalists from outside the institution who were required to abide by the rules issued by the communications officer. Photographic and film coverage of contemporary events related to the fight against terrorism necessitates a different approach. As evidenced in the Sahel where France has stationed troops since 2013. At the start of intervention, only official photographers were authorised to observe operations, as much to abate the military command’s fears of seeing journalists being taken hostage as to manage communications surrounding military operations. In fact, when hostilities broke out, the only images available were those of preparations and logistics, which immediately told the journalism world that Operation Serval in Mali was going to be a war without images. The photos produced by the ECPAD, shot in close proximity to the troops, were only published after the first operations, while the possibilities of observing these same operations were more restricted for journalists. In the battle against terrorism, controlling the image, from when it is taken to where it is distributed, constitutes an alternative war zone, above all in the realm of new media.

In Afghanistan or in Mali, photographers and videographers found themselves once more in the position of directly witnessing skirmishes targeting French troops. This explains why, for several years now, army officers have been equipped with individual firearms in addition to their photographic or film equipment. They might, in fact, be called on to exchange fire to defend their brothers in arms. They are combatants in their own right, exposed to the same risks, as we are reminded by the death of Sergeant Sébastien Vermeille, photographer for the SIRPA Terre (SIRPA’s land army unit based in Lyon) on 13 July 2011 in Afghanistan. In October 2013, the DICoD attached to the French Army Ministry founded the Prix Sergeant Vermeille to honour the fallen officer. It was set up to promote the work of professional civilian and military photographers who accompany, in the field, men and women deployed by the army ministry in France in domestic or overseas operations.

Troops looking for survivors in the ruins of the Drakkar building in Beirut following the attack on 23 October 1983.

© Joël Brun/ECPAD/Défense

For a hundred years, the images produced by army war reporters, archived since the earliest days of the very first units established, have provided a record, evidence and information to support defence communications. Not to mention that they also help the policy of remembrance pursued by the Army Ministry for educational, cultural and scientific purposes. The exhibitions, audiovisual productions and publications made from these images are windows into the history of contemporary conflicts, and pay homage to both their victors and victims. The image collections are an essential medium for educational actions that call on academics to study an archive document and examine the question of engagement, in particular from a modern perspective. As such, the work carried out by war reporters for over a hundred years is an importance feature of remembrance for French citizens, our younger citizens especially.

Author

Constance Lemans-Louvet - Document research officer at the ECPAD

Read more

Bibliography

Images d’armées. Un siècle de cinéma et de photographie militaires, 1915-2015, Sébastien Denis, Xavier Sene, ECPAD/CNRS Éditions, 2015.

Feature

Online articles

History of army films, ECPAD

100 years of army photography and film, ECPAD

Presentation of the First World War collection, ECPAD

Photography of the Vichy army (1941-1943), ECPAD

The Western campaign, 10 May to 22 June, 1940 - The work of German propaganda companies, ECPAD

French military cinematographic services during the Second World War, Stéphane Launey, RHA 252/2008

Images of Dîen Biên Phu in the ECPAD collections

The Algerian War as seen by three amateur photographers, ECPAD

1982: France in Lebanon through the lens of François-Xavier Roch, ECPAD

Photos (ECPAD)

The Western campaign, 10 May to 22 June, 1940 - The work of German propaganda companies

German perspectives on the Second World War in the ECPAD’s private collections

Pierre Schoendoerffer, a career at the service of the image

Videos (ECPAD)

The early career of film director Alain Cavalier at the SCA

The cinema of the Vichy army (1941-1942)

German perspectives on the Second World War in the ECPAD’s private collections

Pierre Schoendoerffer: a lesson in cinema

Articles of the review

-

The event

40 years ago, Kolwezi

“Katangan rebels have taken over Kolwezi, President Mobutu has asked France to send troops. You need to rush over to Kinshasa!" The words my father blurted down the phone when his call woke me up on the morning of Whit Tuesday, 1978. When I arrived at Kinshasa airport on Thursday 18 May, I spotted f...Read more -

The figure

The Bayeux-Calvados Awards

For the past 25 years, the town of Bayeux has hosted the annual ceremony of the Bayeux-Calvados Awards for war correspondents. A tribute that is also written in stone with the memorial dedicated to war reports killed around the world that was inaugurated ten years ago.

Read more -

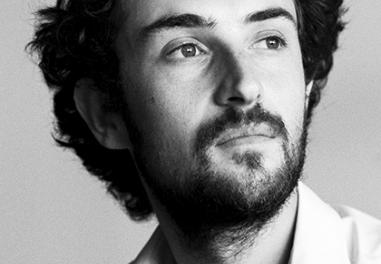

The interview

Édouard Elias

Freelance photographer Édouard Elias has covered major events including the Syrian civil war in 2012 and those in the Central African Republic in 2014. His photographs were recently exhibited at the French Army Museum. For the past several months, he has been reporting the trench war in Ukraine. ...Read more