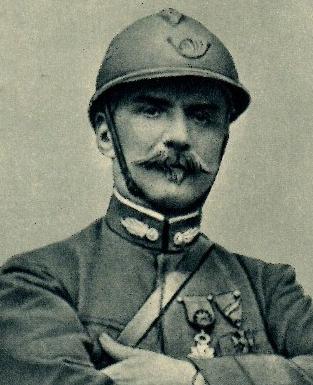

Émile Driant

Lieutenant Colonel Driant is famous for having died at Verdun, on the 22nd February 1916 at the battle for the bois des Caures. But he had previously followed a literary career, under the pen name Captain Danrit, and a political career as an elected MP for the 3rd constituency of Nancy from 1910. Emile Cyprien Driant was born on the 11th September 1855 in Neuchâtel (Aisne) where his father was a notary and justice of the peace. A pupil at the Reims grammar school, he received the top prize for history in the national competition. Affected by the defeat of 1871 and witnessing the Prussian Troops passing through, Emile wanted to become a soldier, going against his father's wishes for him to succeed him. After receiving an arts and law degree, in 1875 he enrolled at Saint-Cyr at the age of twenty. He left four years later to begin a most worthy military career: "though small, he is sturdy, with unfailing good health, very active and always ready; a strong horse-rider and a very strong interest in equestrianism and very intelligent, he has a great future ahead of him" one of his superiors was to write. He served in the 54th infantry regiment in Compiègne and then in Saint-Mihiel.

Promoted to Lieutenant in 1883 with the 43rd infantry regiment, he was posted to Tunis where General Boulanger, then governor general of Tunisia, appointed him as Ordinance Officer - he gave him the hand of his daughter, Marcelle in marriage. Promoted to Captain in 1886, he followed Boulanger, who was then appointed Minister for War, to Paris. Preferring action to political matters, he returned to Tunisia with the 4th zouaves - the Boulangiste affaire would earn him the mistrust of his entourage and a posting far from Tunis, to Aïn-Dratam on the Algerian border. The Driants returned to Tunis and set up home in Carthage where they moved in the Catholic circle of Cardinal Lavigerie, then Primate of Africa. Driant used this lull in his career to write under the pseudonym of Danrit. Success was forthcoming and novels followed: La guerre de demain, La guerre de forteresse, La guerre en rase campagne, La guerre souterraine, L'invasion noire, Robinsons sous-marins and L'aviateur du Pacifique, etc. Along with Louis Boussenard and Paul d'Ivoi Captain Danrit was one of the main writers of the Journal des voyages. His tales were inspired by the Verne style of adventure novel, but retold through the defeat of Sedan and French colonial expansion. The discovery of the world and its wonders evoked the riches that could be drawn upon and the threats to avoid; the extraordinary machines, that for Verne had allowed travel through the air and across the sea, were now primarily the vehicles of war for destroying the enemy. His work is typical of the colonial adventure novel of the 19th century, more specifically of the way of thinking during the years leading up to the First World War. In his writing, a great deal of time was devoted to the army. It confirmed his admiration for great men and his mistrust of members of parliament. It reflected general public opinion, obsessed with the threat of war. It also followed the daily discussions in the press, ever conscious of international incidents (Fachoda in 1898 and the Moroccan crisis provided the narrative framework for L'Alerte in 1911), and of the risk of unrest that they brought in themselves and of the obsession of the decline of France and Europe. Thus, in L'invasion jaune, it is the avaricious capitalist Americans who allow the Asian countries to arm themselves, by selling them guns and ammunition. He also imagined how current arms could be used in great numbers in a worldwide war: deadly gas, aeroplanes, submarines, the role of each invention is considered using the perspective of a large-scale offensive. Officer and fiction writer merged when he wrote his historical trilogy of educational work aimed at young people: Histoire d'une famille de soldats (Jean Taupin in 1898, Filleuls de Napoléon in 1900 and Petit Marsouin in 1901). Captain Danrit thus wrote close to thirty novels in twenty five years.

Recalled to France, the "soldier's idol" was appointed as an instructor at Saint-Cyr in 1892, basking in the glow of his prestige as a military author and visionary: his writings heralded trench warfare. In December 1898, he was made Head of Battalion in the 69th infantry division in Nancy following a four year return to the 4th zouaves. After a short stay in the city of Nancy, he fulfilled his wish to command a battalion of chasseurs. He took command of the 1st Battalion of Foot Chasseurs stationed in the Beurnonville barracks in Troyes. His determination and bravery led him to risk his life on the 13th January 1901 when he intervened to reason with the deranged Coquard in the suburb of Sainte-Savine. Despite his brilliant service record, Driant's name was not on the list for promotion. Politically engaged in right wing Catholicism, he suffered the counter-blows of the prevailing anticlericalism during the years of the law of separation of the church and state, and found himself implicated in a business involving staff records, where officers were graded according to their religious views. A press campaign accused him of having organised a service at the cathedral in Troyes for the festival of Sidi-Brahim and of trying to compromise his men's freedom of conscience by forcing them to attend the service. Suspended for a fortnight, he requested his retirement and decided to enter politics in order to stand for the Army in Parliament; he was then fifty years old.

Beaten in Pontoise in 1906 by the liberal Ballu, he made the most of his collaboration on L'Eclair, in which he published a number of anti-parliamentary diatribes, to take a trip to Germany. As a result of his observations on the large-scale manoeuvres in Silesia, he published a book with the premonitory title, Vers un nouveau Sedan, whose conclusion was most eloquent: "a war that would set us against Germany tomorrow would be a disastrous war. We would be beaten like in 1870, only more comprehensibly than in 1870". These words that first appeared in seven articles just before the elections of 1910, earned him his election in Nancy opposite the radical Grillon. A regular at the sessions of the Chamber of Deputies, mixing Mun's social Catholicism with the thinking of Vogüé and Lavisse, he intervened to pass the bill for military funding, supported Barthou during the vote on the "Salute Bill" which raised national service to three years and protested against the declassification of border strongholds - he managed to save that of Lille in 1912 -. Pre-war he took a keen interest in the brand new military aviation industry. Driant opposed the arguments of Briand and Jaurès, drawing on examples from events in Russia. The army had to play an essential role, above all as a means of educating the working classes and, where applicable, as a counter-revolutionary tool. That was the concept of the military school and social apostolate, which was in keeping with the camp of Dragomirov, Art Roë and Lyautey. He thus became interested in social struggles, in so far as they could compromise national defence. He supported the independent so-called "yellow" trade-unionism founded by Pierre Biétry with support from the industrialist Gaston Japy. They advocated the association between labour capital and money capital. Driant's bills defended the principle of liberty through individual ownership, by means of the progressive participation of workers in the capital of businesses. During the legislature of 1910-1914, the principal ballots of MP Driant included resolutions such as the ten hour day, pensions, freedom of trades unions and various social aid measures.

When war was declared, he asked to return to service and was assigned to the headquarters of the Governor of Verdun to General Coutenceau's department. He requested and was granted command of the 56th and 59th Battalions of Foot Chasseurs of the 72nd Infantry Division, which was made up of reservists from the North and East, 2,200 men in total. He was in charge in the Argonne and the Woëvre. Tested in the fighting in Gercourt, a village in the Meuse that Driant took back from the Germans, his troops did not take part in the first battle of the Marne but were responsible for defending the Louvemont sector. They took back and strengthened the bois des Caures sector. "Father Driant", knew how to listen to his chasseurs, distributed the finest cigarettes and cigars and attended in person the funerals of his heroes at the Vacherauville cemetery. A member of the Army Commission, he was responsible for the bill that led to the creation of the War Cross in the spring of 1915. It was notably he who announced the imminence of the German offensive on Verdun and the lack of human resources and equipment on the 22nd August in a letter addressed to the President of the Chamber, Paul Deschanel: "we think here that the hammer will strike along a line from Verdun to Nancy... If the Germans are prepared to pay for it, and they have proved that they are capable of sacrificing 50,000 men to take a place, they will get through". Despite a visit by MPs, an inspection by Castelnau in December 1915 and a question posed to Joffre by the Minister for War, Galliéni, nothing was done. Moreover, on the 21st February 1916, whilst the army of the Reich concentrated its action on the Verdun sector, only Driant's 1,200 men and 14 batteries faced the attack by 10,000 soldiers and 40 batteries. The Chasseurs held out heroically for more than 24 hours and sustained heavy losses, allowing reinforcements to arrive and maintain the front line. The position of the bois des Caures, held by Driant and his men, was pounded by 150, 210 and 300 mm canons for two days. On the 22nd February at midday, the Germans launched an assault on the chasseurs' positions. Grenades and flame throwers finally overcame the French resistance. Driant gave the order to retreat to Beaumont. Hit in the temple, Driant died at the age of sixty one.

On the evening of the 22nd February 1916, there were only 110 survivors from the 56th and 59th regiments. The announcement of the disaster gave rise to a great deal of emotion. Alphonse XIII of Spain, an admirer of Emile Driant, asked his ambassador in Berlin to carry out an enquiry into his disappearance. They wanted to believe he had been injured, taken prisoner or escaped abroad. A letter from a German officer who had taken part in the fighting at Caures to his wife, provided by his mother, Baroness Schrotter, put an end to the rumours: "Mr. Driant was buried with great care and respect and his enemy comrades built and decorated a fine grave for him, so that you will find him in peace time" (16th March 1916). His sacrifice was used by the press and war publications to galvanise the troops. The Chamber of Deputies officially announced his death and his funeral eulogy was read on the 7th April by Paul Deschanel and on the 28th June Maurice Barrès' League of Patriots held a formal service at Notre-Dame (Paris) led by cardinal Amette. The military man was thus reunited with the novelist ... He was buried by the Germans close to the spot where he fell, although his personal effects were returned to his widow via Switzerland. In October 1922, Driant's body was exhumed. A mausoleum chosen by ex-servicemen, including Castelnau, has been erected there. Each year a ceremony is held there on the 21st February in memory of colonel Driant and his chasseurs who died defending Verdun.