The “Ottoman Auxiliary Battalion”

Sous-titre

Mexican Campaign - 1861-1867

Following several years of political instability and financial crisis in Mexico, in 1861 President Benito Juárez suspended the repayment of loans to the European powers. At the news, the Europeans (France, Great Britain and Spain), encouraged by the conservatives who had been badly treated by Juárez’s liberal regime, decided to intervene militarily.

Thus, a year before Viceroy Ismail (later Khedive; r.1863-79) ascended Egypt’s throne, France, Britain and Spain sent expeditionary forces to Mexico to prop up what would later be known as France’s “Mexican folly”. The affair was over quickly for Spain and Britain, who withdrew in early 1862. But France decided to stay on, as Napoleon III made no secret of his intentions with regard to Mexico. He wished to found a Catholic Latin Empire there, to counterbalance the influence of the United States, and appointed as emperor Maximilian of Austria, who took the throne in 1864. The French troops, under the command of Jurien de la Gravière, were decimated by Mexico’s harsh tropical climate and their numbers reduced to less than half. Gravière recommended the importation of Sudanese Muslim slave soldiers from Senegal and the West Indies, in the hope that they would stand up better to the tropical diseases that were killing off the European soldiers. Thereupon, the French emissary in Egypt approached Viceroy Saïd Pasha (r.1854-1863) requesting the loan of a Negro regiment to serve under the French flag. On 9 January 1863, nine days before the Viceroy’s death, the troopship Seine sailed from Alexandria with 447 men on board. The “Ottoman Auxiliary Battalion” consisted of four companies commanded by officer Yarbit-Allah. The battalion consisted of Egyptian officers and troops serving in the Sudan (then an Egyptian protectorate) and Upper Egypt.

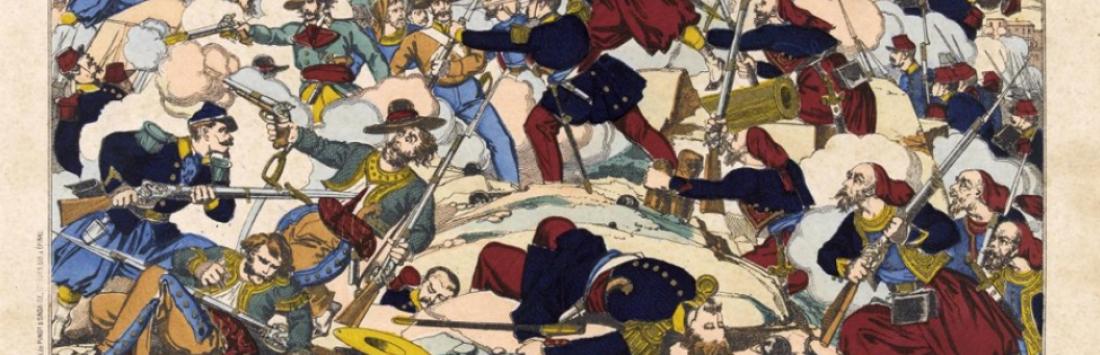

Expedition to Mexico, under the command of Jurien de la Gravière (L’Illustration newspaper, 1862).

Forty-four days later, the contingent, less those who died from a typhoid outbreak during the crossing, disembarked at Vera Cruz. The Egyptian battalion was placed under the command of French commandant Mangin, of the 3rd Zouaves Regiment. To facilitate the chain of command, Algerian soldiers were brought in to help with the language barrier. Once the Egyptian battalion was issued new French rifles (those brought from Egypt were not up to par), the men were redeployed between the port of Vera Cruz and the outpost of Soledad. Their mission was to protect the railway under construction. But the area around Vera Cruz was infested with both guerrillas and banditos led by Mexican nationalist Benito Juárez (1806-1872). Fighting broke out, while a fifth of the battalion had already perished as a result of outbreaks of yellow fever and dysentery. Following a victory against all odds in the attack of 10 June on the town of Mexico (afterwards, Mexico City), General Elias Frédéric Forey continued his advance on Tlalixcoyan, where Juárez had regrouped. Accompanying Forey were 80 members of the Egyptian infantry. Referring to these soldiers a French commander remarked, “these were not fighting men, these were lions.”

Martinique volunteers and soldiers of the Egyptian battalion, by Henri Boisselier, after a drawing published in L’Illustration.

In the meantime, Juárez, who by now was acclaimed a national hero, was propped up with American money and diplomacy. The United States was not about to welcome an imperialist European implantation in its backyard. In fact, France’s request to Khedive Ismail (who had replaced his Uncle Saïd Pasha) for the enlistment of more Egyptian battalions had met with violent protest from the US government on the grounds that “it would increase the Negro population in America”.

As war dragged on, the French government started to feel the financial pinch. Moreover, the flack from the opposition at home had grown to intolerable levels, as the French people turned their attention away from Mexico to the threat from Bismarck’s Prussia. Napoleon III therefore bailed out, abandoning his fellow monarch to the mercy of the Mexican republicans.

Emperor Maximilian I

The 326 survivors of the Egyptian battalion left Mexico in 1867. Since many among them had learned French during the Mexican campaign it was with perfect ease that they spent time in Saint-Nazaire, France, on their return journey home. On 9 May 1867, Emperor Napoleon III, accompanied by Shahin Pasha, the commander-in-chief of the Egyptian army, reviewed the Egyptian battalion during its passage through Paris. Fifty-six men were decorated with the Légion d’Honneur, while Mohammed Almaz received the Officer’s Cross from the hands of the French Emperor himself. Egypt’s returning combatants were greeted by a jubilant population in Alexandria two weeks later, and were reviewed by Viceroy Ismail at a special banquet in Ras al-Tin Palace on 26 May. Almaz was promoted to colonel and the rest of the troops were collectively upgraded.

Original source article (in English)

Ministry of the Armed Forces/DPMA/SDMAE/BAPI - Office for Educational Actions and Information Vaea Heritier