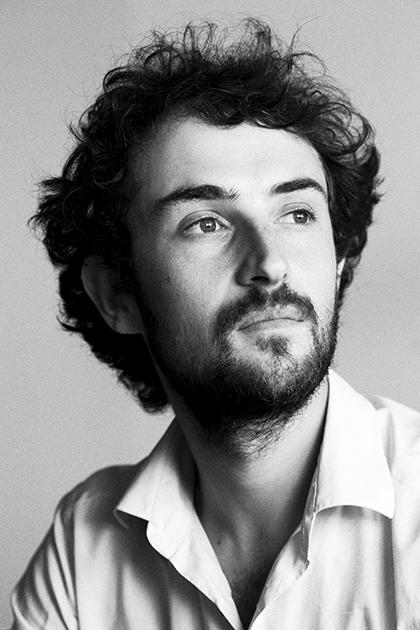

Édouard Elias

Freelance photographer Édouard Elias has covered major events including the Syrian civil war in 2012 and those in the Central African Republic in 2014. His photographs were recently exhibited at the French Army Museum. For the past several months, he has been reporting the trench war in Ukraine.

How at the age of 21 does one decide to venture off to photograph the war in Syria? Did you have a special interest in conflict zones?

It’s partly due to my family background. I grew up in Egypt and France. After my parents died, I was brought up by my grandparents. My grandfather was in the military - he was a maquisard in Creuse in 1941 and then a soldier in Indochina and in Algeria. I was fascinated by his stories, what he experienced, his capacity to exceed his own limits and the profound respect he had in the commitment of the combatant even to the point of thinking about it from the enemy’s point of view. I think this has had quite an influence on the way I work in the sense that I take care to avoid making uninformed judgements.

When I was 19, I gave up business studies and enrolled in photography school. When I was doing my end-of-year work placement, I went to Turkey to visit the Syrian refugee camps. I had no intention of going to Syria. But once I was there, I met various people and those encounters finally led me to Aleppo. That was back in 2012.

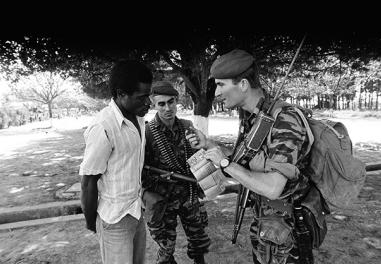

And after Syria, the Central African Republic. The photos you took over there were shown in the exhibition “Dans la peau d’un soldat” (In a soldier’s skin) at the French Army Museum. How did that make you feel?

What moved me was this thread woven through the generations, between my grandfather, his history, and the legionnaires today. When you are in the Central African Republic (CAR), everyone talks to you about the Foreign Parachute Regiment (REP) whereas here nobody really knows about it. Also, showing photos of legionnaires, who will survive them and survive me, at the Invalides, at the very place where they pay tribute to soldiers who have fallen for France, is to honour them.

This exhibition felt like a point of pride and not to mention also a small victory. My intention was to take photos of these men going about their daily routine, in moments of waiting, doubt, occasionally in pain. Because the life of a soldier is not just about pride, honour, glory.

The greatest strength of anyone leaving for a war zone, whether they are a soldier or not, is what they are prepared to give to achieve their aim. I really got to love these guys with whom I developed a relationship based on trust. Too, there are certain photos that I chose not to publish.

You were very young...

I was 23, not all that young really. Yes, if you compare me to the old fighters with 50 years of service, but today all those considered war reporters, even though I’m not that keen on the term, like Patrick Chauvel, for example, started out aged 17-18.

If you don’t like the term “war reporter”, how would you describe yourself?

I’m really a photographer. More a photographer than “photojournalist” as some might like to label me. I tell stories through photography. I’m interested in form because it makes sense. Each report calls for a distinct approach which is determined by the choice of camera, the frame, if you take it in colour or black and white, if the image is posed or not, if its texture has grain or not...

Plus, I don’t only work in conflict situations, even if am more naturally drawn to combat zones. I also work for the press such as Gala in France and VSD, who can send me to report in these war zones or to cover another subject. I rarely do portraits, but as for the rest I handle a wide variety of commissions. The money I earn from short-term assignments funds my trips abroad that demand more time. Because editorial offices are more reticent to send journalists, whole teams and above all photographers to cover a conflict unless its major news. Regarding the CAR, for example, nobody would send me, so I offered to do it as I wanted to go. Through a friend, Didier François, who acted as my guarantor, I made contact with the French delegation for defence information and communication (DICoD) who trusted me and let me go without a real commission. Plus, I’d just been released from prison three months earlier which didn't seem to worry them. Once I was there, I decided not to send any photos. I didn’t publish anything.

When you’re in the field, the way you work changes depending on the media channel you're working for. For example, with the AFP, I had to send my photos within 48 hours max. That’s what I did in Syria. I’d gone over with a friend Olivier Voisin who also worked with the AFP. At that time, many documentary channels like those on the BBC network were sent images already edited while people were ignorant to the reality of the field, which distorted the analysis conducted by the editorial offices and skewed public opinion in Europe. Everyone thought the rebels were on their way to winning the war—it was the media that presented the idea of a rebel victory—because they had conquered 70% of the territory but this wasn’t what was really happening. On the ground, fewer offensives were being led and movement had stabilised in Aleppo since July 2012. They were heading to attrition warfare while the editorial offices believed they were still in a manoeuvre war. Neither were they interested in the photo reports we were producing with my mate Olivier of kids ferrying munitions to the front line. They wanted images of warfare.

After that, we were split up from Olivier, I went west and he headed east. We both got to photograph fighting but he was killed. After that, I wanted to stop sending images directly from the field. Because I felt I didn’t have the right to be there nor the necessary objectivity to do a good job. I preferred to take my time, meet people, earn their trust and send my report after. Which is what I started to do in the CAR. It’s important to explain the context of my situation.

In the CAR, my plan was to go for a longer period (a month plus travel time) and ask for an advanced outpost. They told me “it will be with the Foreign Legion”, the 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment (REI). I then found out that it was regiment based in Nîmes, the town where I was born! I grew up in Uzès. I gathered some material on them with my pals from the ECPAD. I didn’t know anything apart from the myths you hear about the Legion. So I headed to the Central African Republic with some food provisions. I was met by the communications officer on site, a real tough character, the only woman on a base of 200 legionnaires. She gave me tons of advice so I could go about my work and made things so much easier for me. I established a genuine relationship of trust with her.

ECPAD photographers were there with you too... Was their relationship with the troops different from yours?

Of course. They had a different rapport, they were in the military. That makes a huge difference.

So things weren’t a given for you. Did you have to earn the legionnaires’ trust?

It was a gradual process. When I first got there, I had long hair and introduced myself as a ‘photographer-stroke-journalist’. You can see why they might have been slightly reticent: I was bound to ask loads of questions and be the ‘dead weight’ in the field (I wasn’t armed). As a matter of act I didn't ask any questions, I would simply stay silent and observe them. Then I started going out on all the patrols with them and, little by little, they ended up getting used to my presence and accepting me. Of course, there was some tension at the beginning but relationships were formed and I become part of the group. Which meant I could take any photo I wanted. Almost to the point of them asking me questions about my personal life. From my side, I tried to annoy them as little as possible and adapt to them. The respect was entirely mutual.

Are you still in contact with them?

Four months later, when the report was published in the L’Obs [French weekly news magazine], the army military command felt that showing the legionnaires through a human lens was detrimental to their image as soldiers, before the piece managed to change their minds, as it did the troops in the 2nd FIR. I printed copies for them which they hung up in the corridors. They then invited me up for Christmas with them in 2014. The first time a journalist had spent Christmas with them.

In 2015, I asked the commanding officer if I could take photos of the legionnaires in training in Nîmes. He said yes and invited me to observe them in training for a month. I lost eight kilos. I took part in all the training exercises, with the exception of weapons training, which gave me the opportunity to continue my report and forge even stronger ties with them.

Military photographers take a different approach: they know the field, they respect the chain of command. Plus the legionnaires felt they were performing a communications exercise. The photos they took were delivered to the army and they never got to see them.

So if you’re not there as a communications exercise, what is your goal? To inform? Document?

I produce a record without any analysis. What I show isn't the conflict in the CAR; I share what 15 legionnaires experienced over a month. I don't speculate and I don’t hold a position: I will never say who the protagonists in this war are. I simply present the living conditions of the people I lived with day in, day out. It's just a tiny slice of the entire operation.

It’s also a way of paying tribute to them.

Certainly. I’m not there to defend France’s deployment. You can love your country without agreeing with their decisions. What I’m interested in is why these people are fighting, who are they? What are they prepared to risk for their career, their passion, their hope?

But you are also taking risks to document all this...

In general us journalists take less risks. We are slightly in the background, less exposed than a soldier. Admittedly we go to the same zones but often with troops who are less mobile. It's less risky. For example, we are strictly prohibited from following special forces into the field. That's not our place. With the exception of Syria where there was a lot of confusion, we don’t go where the troops are at their strongest, unless you've integrated the patrol which has been engaged. Sometimes, however, you surprise yourself by almost wanting to be in the patrol which will be engaged. You’re half expecting it to happen even if we have a tendency to be a bit cynical. You can get to a place and think “so, is it being bombed or what?” In Ukraine, for example, at one point I felt frustrated because there was less bombing... You build relationships with the troops, you start to share their expectations, their feelings.

Did your experiences in Syria ever prompt you to question your choice of career?

Quite the opposite in fact. Precisely because I never regretted one second going there, I’m still doing what I do. But differently. Lots of people think that... and that’s exactly why I never give interviews about it. I don't have any problem speaking about the details and the conditions of my incarceration. It was a life experience, an occupational hazard but one that doesn't define me, I try to continue my work and push that to the back of my mind. I worked like a crazy person.

So after the CAR, do you have any more plans to report on overseas operations?

Yes, but I still want to observe the rank and file, not the special forces. What I’m interested in are the faces of the soldiers and to take photos of their everyday lives. What I’ve done with other armies, I’m doing with the Ukrainians.

Is that one of your future reporting projects?

Currently, I’m working on a big project in Ukraine. I’ve already been over several time, but this time I’m going to take photos of both sides of the Russian front. I’ve decided to go with black and white film! Again, it’s not the conflict itself I’m interested in but the troops and the trench war.

Have you noticed any similarities between this experience and your experience with the troops in CAR? I mean in terms of camaraderie, sharing these intimate moments, the waiting as you mentioned before?

I didn't manage to capture it on camera, but yes. With the difference that these men are far more exhausted, they’ve been there for a year and a half, and they know that on the other side are friends and relatives. There are even cases where the father is stationed on the Russian front and the son has been enlisted to the Ukrainian side. It’s not the same context at all.

It’s a desolate no man’s land… it’s quite traumatising. My goal is to document their living conditions as this is an attrition war and the men are living deep in the trenches. My work in Ukraine is to show all that: the destruction, the fatigue of the troops, monuments to glory in the patriotic age. We have literally been plunged into an ideological war with pro-Europeans on the one side fighting pro-Russians on the other all accusing one another of being neo-Bolsheviks and neo-Nazis. And the references go back to the First World War and the Second World War. The monuments are crazy... Opposite statues to the glory of the USSR and at the same time what the USSR subjected them to. It’s mental!

There are still lots more reports to do in this region. But I also want to go to Abkhazia. To learn more about the concept of ‘frozen conflict’.

For each assignment, the aim is to take photos in an alternative way, depending on the subject. Our tool needs to do justice to the subject. Of course, I will add colour but for this report I wanted to test out this technique, a more traditional approach to photography. My cameras weigh five kilos each... you get four photos per film, it’s indescribable torture. But if they managed to do it before, why can’t I?

Have you ever taken an interest in reporters who covered much earlier conflicts? Do you have any role models?

I don’t necessarily know the names but I know the photos. I tend to know better the Christopher Griffiths or Don McCullins of this world than the military photojournalists who generally never publish their photos or at least don’t turn them into publications. There are very few books by military reporters.

You also went to Italy recently.

Yes, two months ago for Amnesty International following refugees as they travelled across Italy. Before that I headed out on the Aquarius, the boat collecting refugees from the middle of the Mediterranean. I’m in the process of putting together a coffee table book on the subject. There are so many interesting reports to do that I don’t stop to focus on one particular subject.

As a freelancer, have you ever come against certain limits?

Now, for example, I’m going to Ukraine, on the Russian side, with a photographer from L’Humanité [French daily newspaper] which gets me the necessary accreditations. But I prefer to freelance so I have absolute control over my photos. However, you always run into obstacles.

When I left for CAR, the French army was my main constraint. But I always manage my subject according to the limits put before me. They are never a problem if you know what they are and you respect them. Also, you can always take photos and not publish them. That’s also what I love about photography. I could never write a text or perform an analysis.

But your photos are there for everyone to analyse and interpret in their own way...

That’s true. The aim is to pose a question without casting judgement or taking a position: for example, I’m not saying what the Russians are doing is good or bad. And I’m aware that my images could be used with deliberate intent...

But you have the freedom to accept these publications or not...

That’s exactly it. I do have this freedom. I have absolute faith in the Army Museum, for instance.

Interview on 31 January 2018

Articles of the review

-

The file

Reporters of war

During the Great War, the only pictures sent back from the front were those taken by military photographers. Civilian photographers were not permitted to cover the events as they unfolded. One hundred years later, alongside civilian reporters, enlisted reporters continue to document...

Read more -

The event

40 years ago, Kolwezi

“Katangan rebels have taken over Kolwezi, President Mobutu has asked France to send troops. You need to rush over to Kinshasa!" The words my father blurted down the phone when his call woke me up on the morning of Whit Tuesday, 1978. When I arrived at Kinshasa airport on Thursday 18 May, I spotted f...Read more -

The figure

The Bayeux-Calvados Awards

For the past 25 years, the town of Bayeux has hosted the annual ceremony of the Bayeux-Calvados Awards for war correspondents. A tribute that is also written in stone with the memorial dedicated to war reports killed around the world that was inaugurated ten years ago.

Read more