Isabelle Zdroui

On 16 July 1942, Isabelle Zdroui escaped the Vel d’Hiv roundup. After escaping from the family home, she was hidden in a number of different children’s homes until the end of the war. Today aged 90, she continues to tell her story.

What memories do you have of the early years of the war?

I was eight years old when war broke out. At the time, my sister and I were at the preventorium in Banyuls-sur-Mer (Pyrénées Orientales). We returned to Paris in October/November 1941, for the start of the autumn term. My father wasn’t at home. We asked my mother where he was, but she refused to tell us. I learned subsequently that he had enlisted as a volunteer in 1939, and had been assigned to the Marching Regiments of Foreign Volunteers (RMVE), before being demobbed then “invited” to present himself for the “green ticket roundup” [Editor’s Note: the “green ticket roundup” was the first wave of arrests of foreign Jews by the French police, on 14 May 1941]. He was taken to Beaune-la-Rolande, then Compiègne, before being deported to Auschwitz on 5 June 1942. My parents were both born in Poland. They came to France in 1930 to escape the pogroms, and they worked as market stallholders. We weren’t very well off and lived very simply.

Could you tell us what happened on 16 July 1942?

We heard a knock at the door. My mother didn’t answer it. The caretaker told the police we weren’t in. After they had gone, my mother turned to my sister and me. She was worried, and didn’t know how we were going to manage to get out of the flat. To leave meant crossing a courtyard, where we would be in full view to everyone. We went into the kitchen and opened the window that looked onto Boulevard Diderot. A neighbour was crying and said: “Go downstairs. I will meet you there and save you all.” My mother preferred a different solution. There was a low wall near the kitchen window. The three of us climbed onto it and waited there hidden for hours, pressed against the wall. Across the street, a policeman watched us without saying a word. The caretaker came back to tell us the danger had passed. She advised us to get away as quickly as possible, because they would be coming back the next day. Mother got a few things together, then handed us over to a lady. From then on, my sister and I went to different childminders and children’s homes. Later, the Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants sent us to a little farm, where we were very badly treated, before transferring us to a religious institution in Vatan, Indre, where we stayed until 1945. There, the conditions were very good. Mother, who had been staying on a farm a few miles away without realising it, came to collect us after Liberation.

How do you rebuild yourself after such an experience?

It was very hard, but I managed to do so by researching my family history and with the support of my husband. We had suffered the same hardships. A few years ago, we discovered that our fathers had been at Compiègne at the same time and left in the same convoy, number two, on 5 June 1942.

You mention researching your family history. What did that involve exactly? What did you discover?

I began my research to find out more about my family history, of which I knew very little. It proved an arduous task, due to the difficulty getting hold of the documentation. I had lots of questions about what my parents’ lives had been like before the outbreak of war and what had happened to my father. I didn’t know what had become of him, where he had ended up or what camps he had passed through. The same went for my father-in-law. My enquiries enabled me to piece together part of my past. Today, I still carry out research before talking to schools. The two go hand in hand. When I look for information about deported children and come across documents about families, I pass them on to the people concerned. In a way, I help them obtain information about the trajectories of their loved ones and their fates. It’s important to know the truth.

You and your husband continue to share your personal stories. Why is it important to you?

It is quite normal to want to share one’s own story, and I have made a point of doing so regularly since 2005. People need to know what happened, especially children. I look back with them over the events of the war, because often their parents don’t talk about it with them or themselves don’t know what happened. Most of the students listen without asking any questions, but they clearly take an interest in what is being said. One day, I bumped into a little girl from one of the school groups I had spoken to. When she recognised me, she turned to her father and said: “That’s the lady who came and talked to us about what I told you.” He looked at me and said: “You’re doing the right thing, madame. Nothing from that period should be forgotten.”

Articles of the review

-

The file

1942: a turning-point?

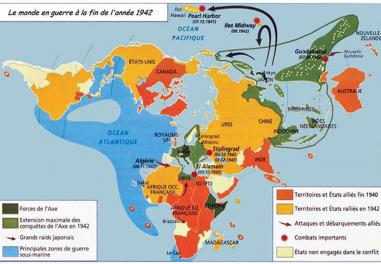

If Japanese victory in the Far East and the advance of German troops into the Soviet Union made 1942 a difficult year for the Allies, it was also one of hope, with the German defeat at Stalingrad and the Allied landings in North Africa. In France, popular support for Vichy waned, as the Resistance o...Read more -

The event

80 years after 1942

Read more -

The figure

Memorial to the Landings and Liberation of Provence

A Major National Remembrance Site of the Ministry of the Armed Forces, the Memorial to the Landings and Liberation of Provence bears witness to the history of the Second World War. The episodes that took place in the Mediterranean in 1942 will be at the heart of its cultural programme this year. ...Read more