Resistance in Europe

Contents

Summary

DATE: 1939-1945

PLACE: Europe

OBJECT: Resistance to the Third Reich

More than 70 years on from the Second World War, the resistance continues to be an endless source of speculation for experts. It is often studied and understood in the light of regional and national history. Over the past few years, there has been a shift in scale to try to zero in on a Europe-wide history of the resistance movements.

The victories won on all fronts between 1939 and 1941 enabled Nazi Germany to impose its domination on the entire European continent. Everywhere, the ensuing occupations triggered a phenomenon of resistance that combined patriotic motives (freeing an occupied country) and other, more ideological ones (combating Nazism, restoring democracy or taking advantage of the defeat to introduce communism).

The European resistance movements varied considerably according to the type of occupation put in place by the victor, the earlier political situation in the countries concerned and their relationship with the Allies. German resistance to Nazism will not be addressed here, since it did not take place in a context of occupation and therefore involved different processes.

More or less spontaneous resistance

In the occupied countries, resistance movements emerged more or less spontaneously depending on the type of occupation imposed by the Reich. Where the German occupation involved the total liquidation of the national State, creating a political vacuum, resistance developed almost straight away. In Poland, the Nazis’ project of colonisation and genocide was apparent from as early on as the military campaign of September 1939, and an underground government was formed even before Warsaw had surrendered. In a Czechoslovakia dismembered by the Reich, the non-communist Resistance united in spring 1940 to form the Central Committee of Resistance. In Greece and Yugoslavia, the harshness of the occupying regimes installed in the spring of 1941 similarly explains the immediate formation of resistance groups, which sought to continue the fight undeterred by the defeat of their regular armies. For many occupied countries, the fact that their legitimate governments had gone into exile in London, in order to carry on the fight from there, facilitated the birth of an internal Resistance and gave it a high degree of legitimacy. This was the case for the governments of Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, which became points of reference outside France following their countries’ defeats.

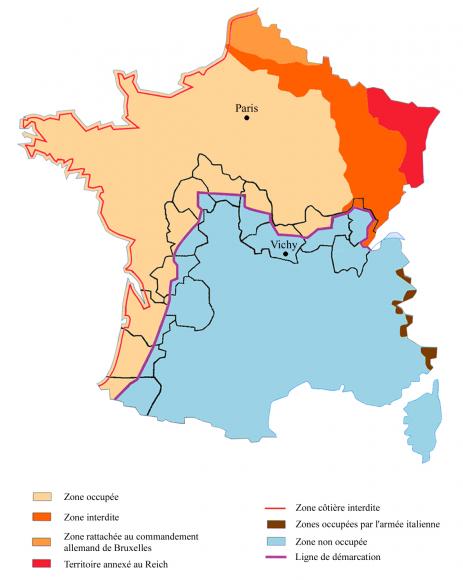

Two countries saw a specific situation due to a different system of occupation. France was not totally occupied. Whereas a German military administration was put in place in the occupied zone, the southern zone was controlled by a French government installed in Vichy, which embodied a form of continuity of the State, despite a complete break with the republican regime. The personality of Pétain reassured the people. De Gaulle – who had gone into exile in London and on 18 June called on the French to refuse to accept defeat – carried little weight against the “Victor of Verdun”. The early days of Free France weren’t easy, and few rallied to the cause through the summer and autumn of 1940. Against this backdrop, unlike in other occupied countries, resistance was by no means a given in France in 1940. It meant infringing the instructions given, breaking with a State that remained in place and disobeying Marshal Pétain, whose prestige was immense. Although small, isolated acts did take place in the wake of the defeat, those “trying to make a difference” had to come up with a resistance that did not in fact exist.

It was not until late 1940/early 1941 that the first forms of organised resistance began to appear. Yet for some sectors, particularly those that had pledged allegiance to Pétain (the military, civil servants), dissidence was not an option until after November 1942, when the total occupation of France had wiped away any remaining illusions about Vichy. Within German-occupied Europe, only Denmark presented a situation comparable to that of France, since the Germans preserved its institutions (the king, government and even the army). As in France, those wishing to stand up to the regime had to break with the government of their own country, thereby running the risk of appearing as traitors to their homeland. This situation persisted until summer 1943, when the occupier declared a state of siege.

Political resistance to Nazi occupation

Unlike the image that was to become cemented by the end of the war – of armed Resistance fighters joining in the liberation of their countries alongside Allied troops – resistance usually began as a political act, involving various actions to demonstrate a refusal to accept the order imposed by the German victors. In Poland, most political parties went underground and were represented in an underground parliament, the National Defence Council, set up in November 1939. To oppose the Reich’s Germanisation plans, the Polish Resistance adopted a strong cultural component, setting up parallel schools and establishing an underground press of considerable size (1500 titles). An underground society developed across all spheres: universities, factories and fields.

A country with a long tradition of underground political struggle, due to the various occupations to which it had been subject throughout its history, Poland is nevertheless a special case. In most occupied countries, the traditional political structures collapsed with the defeat and were not immediately reproduced underground to give tangible form to the Resistance. Resistance therefore had to be conceived out of non-existent structures. Only the communist parties conducted an underground struggle from as early as 1940, and even that followed a specific course up until spring 1941, due to the pact of neutrality between the USSR and Germany. Although, during that time, communists throughout Europe continued to circulate their underground newspapers and pamphlets, and tried to mobilise the masses with various kinds of protests and strikes, their goal was first and foremost to denounce an “imperialist war”, whose first victims would be the working class, rather than laying the foundations of resistance to the Reich.

The launch of Operation Barbarossa, in June 1941, put an end to this strategy, and European communists revived the anti-fascist tradition which had been their hallmark before the war and plunged into a direct assault on Nazi Germany.

Due to the vacuum left behind by the collapse of traditional structures like political parties and unions, which could have been used as a means of organising resistance, small resistance groups were formed from work, religious, friendship or family networks. They sought to carry out counter-propaganda and information actions, to prevent free rein being given to the official line taken by the Germans and their auxiliaries. Those actions consisted of printing pamphlets or, when more resources began to become available, underground newspapers. Because a newspaper required editorial staff to write it and teams of people to distribute it, setting up a newspaper often involved the development of a “movement”, which became the main form of resistance organisation in the countries of northern and western Europe. In Belgium, where memories of the First World War occupation remained vivid, the first underground newspapers took the titles of their predecessors, for example La Libre Belgique. In the Netherlands, one of the very first victims of German repression was a painter and decorator from Utrecht, who had begun producing and distributing pamphlets in May 1940. By 1941, the number of underground publications in the country had reached around 120, with a combined circulation of over 50 000. By December 1943, that figure stood at 450 000. The underground press in Norway comprised more than 300 newspapers. In Denmark, where underground propaganda was stepped up in 1943, when the country came under a state of siege, there were 538 underground newspapers – a European record – with a circulation of 11 million. In France, the first underground publications appeared at the very end of 1940 and in 1941, in the occupied zone (Résistance, Libération-Nord, Défense de la France) and the southern zone (Liberté, Libération Sud, Franc-Tireur). All of the movements that were to enable the French Resistance both to organise itself and, in 1943, to become unified as the MUR (United Resistance Movements) were built around a newspaper, usually of the same name.

Supporting the Allied war effort

The European resistance movements were established in a national setting, but the wider context was one of world war. Resisting therefore meant supporting the Allied war effort. Links soon developed between Britain, the only country still fighting the Reich in 1940-41, and the national resistance movements. Those links were aided by the presence in London of governments in exile or a personality like de Gaulle, who sought to represent “combatant France” where the French government had opted for collaboration. The national resistance movements could not exist or develop without help from outside. Meanwhile, the British needed the help of the Resistance on the continent to combat the Reich. In July 1940, a Special Operations Executive (SOE) was established to “set Europe ablaze”, in Churchill’s words. Its agents were sent to all the occupied countries to make contact with the national resistance movements. Among the SOE’s successes was the execution of Heydrich in Prague, on 27 May 1942, by two Czechoslovakian agents parachuted into their home country after being trained in Great Britain.

The first escape networks, or “lines”, to emerge on the European continent responded to this need to aid Great Britain. British soldiers who had not managed to be repatriated from Dunkirk found themselves stranded on French soil. They, along with RAF airmen shot down over northern France, Belgium or the Netherlands, who were similarly intent on getting home, used networks to get to the south of France, then on to Spain and Gibraltar. With the aid of the British secret service, the first networks specialising in helping Allied soldiers were set up in the summer of 1940. Operating across northern Europe and southern France, they were the only transnational resistance organisation. Ian Garrow, a Scottish officer, created one of the biggest, which ran all the way from Belgium to Marseille and Perpignan. When Garrow was arrested in July 1941, a Belgian doctor, Albert Guérisse (Pat O’Leary), took over. Up to the end of the war, the Pat O’Leary Line helped 600 Allied soldiers and airmen to escape. Another example of a transnational network was the Comet Line (Réseau Comète). Set up in Brussels in the spring of 1941, the Comet Line aided nearly 700 Allied servicemen, and succeeded in smuggling 288 of them into Spain.

There were also networks specialising in intelligence, which provided London with strategic information about the Germans’ military intentions, Wehrmacht troop movements and military infrastructure built in the occupied areas (air, naval and submarine bases). Some of these intelligence networks worked directly for the British secret service, such as Alliance in France. Others were linked to the secret services of the governments in exile in London. Some networks also worked for the Soviet intelligence services, like the famous Red Orchestra, which had branches across Europe.

Armed resistance

In the countries of eastern and southern Europe, resistance to occupation soon took the form of armed struggle. In Poland, an underground army, the AK, was set up as early as autumn 1939. In Yugoslavia, pockets of resistance were formed in the wake of the surrender of the regular army, by elements of the army who took refuge in the mountains. In April 1941, General Mihailovic headed up into the Serbian Ravna Gora mountains with a group of soldiers to found the Chetnik movement and carry out guerrilla operations against the German and Italian occupiers. Yet he was faced with the emergence of another “warlord”, the communist Josep Broz (Tito), who on 4 July launched an armed uprising from the mountains of Montenegro. In Greece, the first groups of andartes (guerrillas), formed by members of the armed forces who had taken refuge in the mountains, appeared in Macedonia in autumn 1940. In September 1941, the Greek Communist Party (KKE) founded the National Liberation Front (EAM), which soon gained an armed branch, ELAS, that carried out regular attacks throughout 1942 and controlled whole regions of the country.

This same identification between armed struggle and resistance to the occupier was also found in the countries of the Soviet Union that fell under German control in the months following the launch of Operation Barbarossa. Entire units of the Red Army were surrounded by the Wehrmacht as it advanced towards Leningrad in the north, Moscow in the centre and the Caucasus in the south. Refusing capture, some of these units formed bands of partisans who, between 1941 and 1944, waged an intense guerrilla war behind the German lines, and mobilised as many as 500 000 combatants, in particular in Ukraine and Belarus.

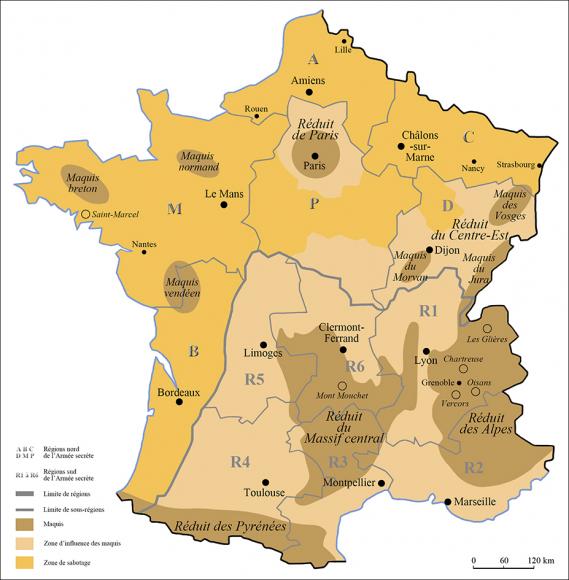

In western Europe, nothing comparable to this “partisan warfare” was seen until the last year of the war. In France, the phenomenon of the maquis (rural guerrilla groups) began developing in the spring of 1943, when the conscription of labour to work in Germany led to the emergence of camps of objectors, which were transformed into combat units by the Resistance. Yet despite a few attempts to form “enclaves” in the Alps or the Massif Central, the phenomenon remained limited compared to the experience of partisans in the Balkans, where entire regions were in the hands of rebel groups, which both carried out guerrilla operations and governed the areas under their control.

In this regard, the French maquis were closer to the Italian partigiani, established in the north of the country in 1943-44. The overthrow of Mussolini and the signing by the Badoglio government of an armistice in September 1943 led the Germans to take control of the northern provinces of the peninsula and reinstall Il Duce at the head of a nominally “social” republic. The country was plunged into civil war. As in France, the Italian partisans took no decisive victories against the Germans before the arrival of the Allies, and the areas under their control did not exceed a valley, plateau or canton in size.

Joining in the fighting for liberation

While the development of the European resistance movements was shaped by internal factors linked to national events, it was also situated in the global military context. Autumn 1942 and early 1943 marked a turning point for the Resistance across Europe, as the Reich’s first major defeats (El Alamein and Stalingrad) showed that the course of the war was changing in the Allies’ favour. That turning point meant the resistance movements could begin preparing for the coming fighting, even as German repression was being increased everywhere. As the endgame approached, with a number of Allied landings organised in the west and the Red Army offensive on Germany in the east, the national resistance movements mobilised, in some cases triggering genuine uprisings. To coordinate resistance operations, Allied commandos (Jedburgh teams, SAS) were parachuted behind enemy lines, in France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Guerrilla actions were stepped up across Europe to paralyse German transport routes. The Greek and Yugoslav partisans, and to a lesser extent the French and Italian maquis, went on the offensive. There were urban uprisings in cities like Warsaw and Paris. National resistance movements could not have liberated their countries from occupation single-handedly. That does not mean they did not speed up the liberation process, providing considerable assistance to the Allies and immobilising substantial German forces through their actions.

But the conditions in which that liberation took place also had far-reaching consequences. In Western Europe, the Resistance managed to unite, thereby avoiding the torments of civil war. The geostrategic situation and liberation by the Americans also explain why Moscow did not encourage the French Communist Party to break the unity built during fighting against the occupier. In Eastern Europe, however – “liberated” by the Red Army – nationalist organisations were systematically eliminated to pave the way for the communists to take power. Stalin allowed the Germans to crush the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944, rounding up all the leaders of the non-communist Polish Resistance. The members of the underground parliament were arrested and tried in Moscow. In the Balkans, nationalists and communists, in complete disagreement over the kind of regime to install after liberation, never managed to unite in the fight against the occupier. As soon as the Germans had left, Greece and Yugoslavia descended into civil war.

These contexts explain the differing post-war legacies of the European resistance movements. Whereas in the East the communists seized power with help from Moscow, the unity of the Resistance in the West enabled democratic institutions to be restored and a consensus to be reached around reforms that led to the establishment of a welfare state, offering the people new prospects after years of oppression. Although no transnational resistance institutions had been set up during the war, the fact that they had taken part in a continent-wide shared struggle reinforced pro-European feeling among many Resistance members after 1945.

Author

Fabrice Grenard - Fondation de la Résistance

Read more

Une histoire de la Résistance en Europe occidentale, Olivier Wieviorka, éditions Perrin, 2017.

Sans armes face à Hitler : 1939-1945, La Résistance civile en Europe, Jacques Semelin, éditions Payot et Rivages, 1989.

Articles of the review

-

The event

75th anniversary of the Normandy landings

Every year since 1944, Normandy remembers the Allied soldiers who landed on its beaches to fight for the liberation of France and Europe. The 75th anniversary of the landings, on 6 June 2019, is a particularly symbolic date. ...Read more -

The figure

Resistance in the Netherlands

The Dutch Resistance Museum (Verzetsmuseum) in Amsterdam is a window onto the history of the German occupation and the Nazi regime in the Netherlands. Since 2013, children have been able to learn about the Netherlands Resistance at a junior museum especially for children aged 9 and above. ...Read more -

The interview

Rémi Praud

Rémi Praud is director of the Liberation Route Europe Foundation, which offers a trail across Europe in the footsteps of the Allied soldiers. In this 75th anniversary year of Liberation, the European partners are preparing to receive visitors in their droves. ...Read more

Related articles

- La France en guerre 1939 - 1940

- La politique des otages sous l'Occupation

- The Resistance

- The Resistance Movements

- Les réseaux

- The Resistance and the Networks

- The maquis

- The unification of the Resistance

- La Résistance en France en 1944

- La Résistance en actes

- La préparation de l'action subversive

- Sabotage

- In the footsteps of the Resistance in Lyon

- The Resistance in Bigorre (65)

- The resistance in Corrèze and Creuse

- The Resistance in the Haute-Vienne department

- Les cinq étudiants du Lycée Buffon

- Les étrangers dans la Résistance

- Les Polonais en France 1939-1945

- La presse clandestine