Teaching and passing on the Great War

Sous-titre

Interview with Dr Rainer Bendick, history teacher, and Dr Alexandre Lafon, contemporary historian

Rainer Bendick has written a thesis on how the First World War is represented in French and German school textbooks. Since 2018, he has been educational adviser to the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge (VDK), the German war graves commission, in the Brunswick area. A former educational adviser to France’s First World War Centenary Commission, Alexandre Lafon is today a high-school teacher and associate researcher at Toulouse Jean Jaurès University.

Left: Dr Rainer Bendick, historian. Right: Dr Alexandre Lafon, contemporary historian.

How is the memory of the First World War, or Great War, taught and passed on to school students?

Rainer Bendick (RB): The term “Great War” is unknown in Germany. If there is a “Great War” for Germans today, it is the Second World War. That said, the First World War does appear in the school curricula of the 16 Länder. At secondary level, it is always included in a chapter entitled “Imperialism and the First World War”. In Bavaria, for instance, the history syllabus for year 8 (ages 13-14) devotes 13 hours to it, out of a total of 56. The war’s causes are an intrinsic part of studying the conflict; they are even as important as the war itself. The international tensions prior to 1914 and the July Crisis are taught as the defeat of peace, a fatal failure of politics, a tremendous victory of nationalisms and militarisms. The military actions have a limited place in these learning scenarios. But the immense destruction caused by the artillery battles, and the loss of human lives are always presented. There is also a focus on the home front: the war effort and, in particular, the poverty, hardship and hunger of civilians.

Alexandre Lafon (AL): The First World War, known also as the “Great War” in France, is taught at all learning stages. It is first looked at in the final year of primary school (ages 10-11), then in troisième (ages 14-15). At the lycée, it is taught in première (ages 16-17). The curricula stress the idea of an all-out, mass war, both at the front and at home (strikes of 1917). Trench warfare and the Armenian genocide are key aspects in troisième. Through the study of maps, première students gain an insight into the consequences of the war, with the concept of the “suicide of Europe” and the international Battle of the Somme. The conflict has also been included in the new history, geography, geopolitics and political science course option for final-year students (terminale). Theme 3, “History and memories”, looks at the historical debate around the causes of the First World War and its political implications. As well as considering the link between history and memories, this new approach shows the extent to which history can be at the centre of debates involving our interpretation of the world and our political outlook of “living together” in harmony. On this point, and in the context of this theme, a comparison with German memories of the war can be very productive.

Young people visit the Verdun Memorial. © Mémorial de Verdun

Are there events, places and/or names associated with the Great War which should be remembered by young people in France and Germany today?

RB: There is a fundamental difference between France and Germany, since practically no military action took place on German soil, or the places where fighting took place – in East Prussia and Alsace – are not part of the present-day Federal Republic of Germany. Unlike for people at the time, the Eastern Front is almost completely forgotten today. Remembrance today focuses on the Western Front, with its artillery battles and immense destruction, symbolised by Verdun and the Somme. Their names appear in all the textbooks. Photographs of soldiers in the trenches, the mud and the misery, and letters home, transmit the horror of the war. Tasks like “Write a newspaper article with the title ‘The impact of modern warfare on people’”, “Create a collage on the theme of the horrors of war”, or “In a group, design a poster calling for the war to be ended, from a contemporary viewpoint”, allow no room for the soldiers’ heroism. Their actions are seen as destructive, with no plausible, rational justification.

AL: Unlike Germany, France was the main theatre of military operations on the Western Front between 1914 and 1918. Ten French departments were invaded, occupied or annexed. There are therefore many First World War remembrance sites. 11 November remains a key commemorative date, and each year local war memorials serve as the rallying point for this collective remembrance. Nationally – and internationally – the main battlefields have become shared heritage. The proposed UNESCO nomination of the First World War landscapes is one example.

Not surprisingly, Verdun is the number-one remembrance site of the Great War. The Verdun Memorial, renovated in 2016, and Douaumont Ossuary crystallise by themselves the memory of the conflict – the fighting, death and grief – while the World Centre for Peace seeks to situate the Battle of Verdun within the global issue of peace. The Battle of the Marne and the site of Notre Dame de Lorette, with its international Ring of Remembrance, were reopened for the centenary. For a number of years, the Chemin des Dames, in the department of Aisne, has seen a renewed remembrance focus on the victim figures of the mutineer and the executed. This clearly shows a shift from the poilus as heroes to sacrificed soldiers. The figure of Maurice Genevoix, who was admitted to the Pantheon in 2020, condenses these two facets. He has become the “great witness” of the conflict, and with him his memoir, Ceux de 14. The book (published in English as ‘Neath Verdun) will certainly be used more in schools in the coming years. Far more than the memoirs of the great leaders, generals and field marshals, who are today taught less, although Joffre and Pétain (as commander of the French army at Verdun) are still found in school textbooks.

More than a century after the end of the First World War, why is it still important for children to learn about it? What are the challenges to passing on and taking ownership of this memory?

RB: George F. Kennan’s image is a bit dated, but nonetheless profoundly true: the First World War was “the great seminal catastrophe” of the 20th century, and it is crucial to understanding European history since 1918, grasping the long-hidden conflicts that erupted following the collapse of the Soviet bloc, and alerting us to the dangers of nationalism and of a politics which, although full of good intentions, believes a lasting solution to global tensions can be found through military force. This deceptively promising logic of war is what inspired our ancestors in both France and Germany – and destroyed our continent. There is no stronger argument for European integration than the history of the First World War.

Astrid Klinkert-Kittel, District Administrator of Northeim, unveils the information panel created by students

of Bad Gandersheim high school. © Rainer Bendick

AL: To my mind, the challenge is twofold. Firstly, the younger generation are custodians of a remembrance legacy that is still very vivid in France in 2021. The Great War is all around us and is often referred to. In order to become free and enlightened citizens, they must be able to understand the political and commemorative significance of the conflict, as well as grasp its scope. It was most certainly in the trenches that the Republic as a social contract was put to the test and the idea of Europe was born. Secondly, the challenge of passing on this memory has to do with war and peace. As Rainer Bendick pointed out, we must guard against a fascination for the “Great War”, which was also a great material, demographic, social and political cataclysm. The consequences of the conflict were disastrous. We must be wary of thinking of war as a solution. Europe at peace – which teachers could concentrate more on in the classroom – shows us how the path of peace is the best path.

How can young people be encouraged to take an interest in the war, when the traces are disappearing and the “memory in the flesh” is no more?

RB: The traces are still there, and they are impressive! Take the battlefields in France and Belgium, with their extraordinary museums, and in particular the military cemeteries. The cemeteries, along with the war memorials, are the only traces left of the First World War in Germany today, and they are an invitation for some promising initiatives. All German municipalities have a war memorial, erected during the 1920s, often in a spirit of revenge. That is why they appear timeless. They are of genuine educational interest in that they enable students to find traces of the war on their doorstep, in their neighbourhood. They teach young people what the war did to people, to those killed on the battlefields or who were left without a father, a son or a husband. In addition, since they would previously have had a military hospital and therefore a military plot in their cemetery, most German towns have a military cemetery. The French and Belgian branch of the German war graves commission, SESMA, runs school projects on these cemeteries. Students learn about the history and memory of the site, and the fate of the dead. They create visitor information panels and hence become “tellers of history” for their town.

Still more impressive are the school trips to northeastern France. Visiting the vast military cemeteries leaves no student unmoved, and offers many learning opportunities. Finally, I should mention the youth meetings organised by SESMA each year at military cemeteries across Europe, which are a unique opportunity for these future citizens to discover their shared history and to alert them to the folly of war.

AL: It is a big challenge to interest young people in a conflict that is over a century old and has no remaining survivors to pass on the memory (Lazare Ponticelli, the last poilu, died in 2008). Yet the Great War is still an incredibly important presence in our country, renewed every year by the commemorations of 11 November, which remains a key date in our remembrance calendar. It is regularly brought up in politics and society: recall the French president’s speech announcing the first coronavirus lockdown in March 2020, in which he evoked the memory of the First World War. This ongoing presence of the war is fundamental, and ensures the memory of the conflict is continually passed on. It draws on a series of traces and marks that permeate our physical and social landscape: the local war memorials that still stand at the physical heart of town and village life; the high-profile, preserved remembrance sites and landscapes of the war in northern and eastern France; the museums and interpretation centres across the country, which exalt local objects and stories from the war; and finally, the cemeteries, large and small, and military plots, which still bear witness today to the overwhelming grief that struck families and communities. These combined elements, kept alive by family memory, local historians and national institutions, ensure the Great War remains a powerful contemporary presence. School history syllabuses, strongly geared to 1914-18, demonstrate the ongoing desire to pass on the events, drawing on local places familiar to students.

Madame Luquet’s class of 9 to 11-year-olds from École Raymond Aubert, Belfort, receive their awards for the

14th Petits Artistes de la Mémoire competition (2019-20). © ONAC-VG / École R. Aubert (Belfort)

The Petits Artistes de la Mémoire (“Little Artists of Remembrance”) competition has been held by the National Office for Veterans and Victims of War (ONAC-VG) since 2006. It feeds into that process, offering all the necessary ingredients: a local story discovered, a multi-disciplinary approach, a field survey, and an artistic representation that prioritises student involvement and marks their school experience.

How can France and Germany work together to pass on a shared memory of the Great War?

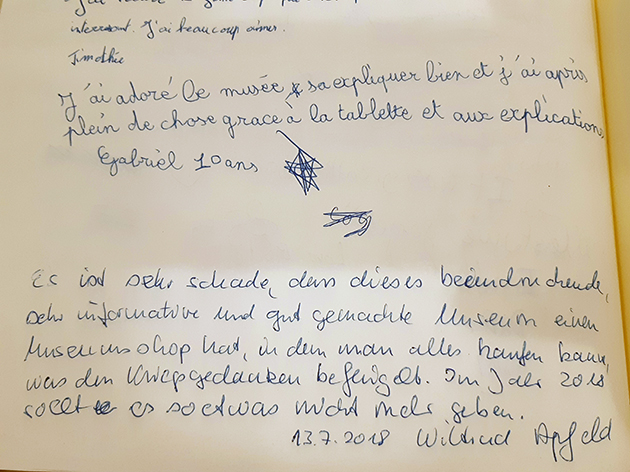

RB: First and foremost, we need to understand that the other’s memory is different from our own. We may have overcome our differences today concerning the war, but the way we commemorate and teach about it causes misunderstandings. The comment left by a German woman in the visitors’ book of Péronne history museum in 2018 provides a graphic example: “It is a real shame that this impressive museum, highly informative and well put together, should have a gift shop where you can buy everything to prompt bellicose thought. In 2018, such things should not exist.” The author of these lines was shocked at the presence of military paraphernalia (plastic helmets, toy soldiers in period uniform, etc.) on sale in the museum shop. In her view, such objects went against the museum’s message calling for us to be at peace with the past. Without taking into account the place of the military in France and the positive image of the armed forces (as protectors of the Republic), she judged the gift shop according to German standards, in particular the distance from the military.

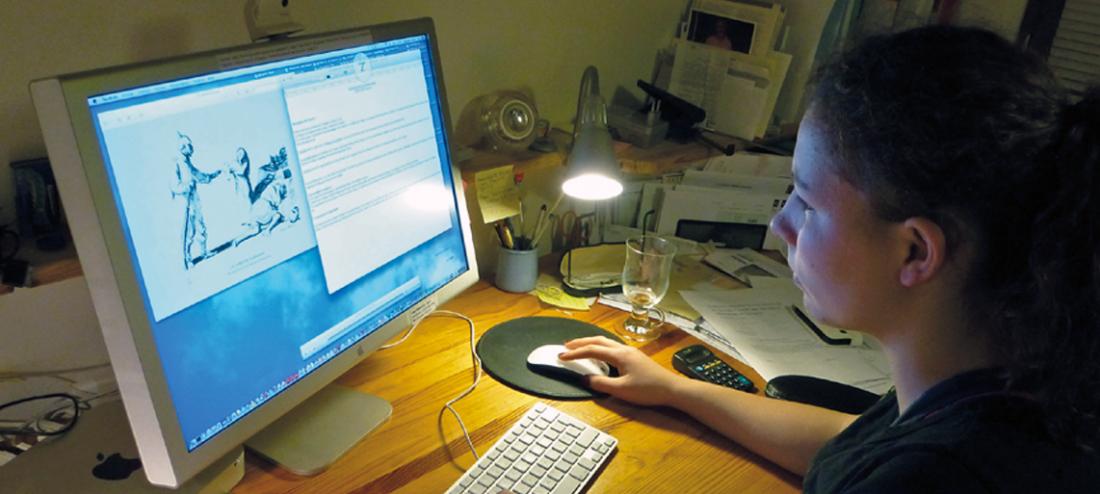

A French secondary-school student from Gap works on a caricature conserved at the Museum of Osnabrück. © Collège Centre, Gap

Binational initiatives in which teachers and students from our two countries work together, like the one entitled “The other’s viewpoint”, are a way of preventing such misunderstandings. Via the internet, students from Osnabrück and Gap worked on a collection of French and German caricatures conserved at the Museum of Osnabrück, which culminated in an online Franco-German exhibition (editor’s note: see end of issue). As co-editor of the Franco-German history textbook, I also suggested the creation of mixed teams to put together our own textbooks and school curricula. This will mean we are more aware of the other’s perspective and in a better position to relativise our own.

Young people take part in the Armistice centenary ceremony at the Arc de Triomphe, 11 November 2018.

© Benoit Tessier/Pool/AFP

AL: The centenary commemorations showed, especially among young people, the extent of the potential divide between remembrance expectations in France and Germany. The misunderstandings seen on the “4 000 young people in Verdun” programme in 2016 illustrate these differences: the German teachers expected the fighting spirit to be challenged, whereas the French teachers wanted their students to gain a better understanding of the key remembrance site of Verdun. The mythologising of the Great War and the still too vivid injunction of the “duty to remember” in France stand in the way of a shared Franco-German approach to contemporary conflicts.

However, some useful avenues were explored during the centenary. Working in pairs, one from each country, participants in the “4 000 young people in Verdun” programme produced some impressive work, supported by the Franco-German Youth Office. In the editorial sphere, the Franco-German Album of the First World War, put together by historians and curators from the two countries and accessible via the website of the German History Institute Paris, attracted media attention to this joint research effort. We must continue along this path, with more and more educational initiatives and research partnerships that interrogate our differences and identify potential common ground: joint planning of key commemorative dates, better understanding of the history and remembrance of important events of the 20th century in both countries, more effective sharing of the way in which we view our countries, Europe and the world today.

A comment in the visitors’ book of Péronne history museum which illustrates clearly the kind of misunderstanding

that need to be avoided through greater awareness of the other’s viewpoint. © Rainer Bendick

In your view, is Germany sufficiently committed to passing on the memory of the Great War to young people? How to tackle the history and memory of a “defeat”?

RB: Seen from France, the memory of the Great War appears neglected in Germany. But stop and think about the Nazi dictatorship and you will understand why the First World War is sidelined in this way. In addition, the Federal Republic does not identify with the Empire. It sees itself as an alternative model of democracy. The defeat of 1918 is not taught as “our defeat”, but as the defeat of the Empire. Hence the “stab in the back” myth (which attributes the responsibility for the defeat to the civilian population rather than the German army) is found in all school syllabuses and textbooks. The resulting destabilisation of the Weimar Republic is also focused on. But I see a danger in this, since putting 1918 in the perspective of 1933 would mean absolving those who destroyed democracy of a tremendous moral responsibility. The great economic and financial crisis of the early 1930s, the six million unemployed, the social deprivation and, above all, the absence of a long republican and democratic tradition in Germany are far more significant in explaining Hitler’s rise to power than the defeat and peace settlement.

How to keep up the momentum which the First World War centenary sparked in France, particularly among young people?

AL: The official educational report for the centenary, presented in March 2019 in Bordeaux with all those who participated in attendance, showed the extent of the in-depth work on remembrance which schools and their partners carried out with students. It was built around students devising their own projects on remembrance and history. They were the protagonists: in the production of their own learning resources or the presentation of their remembrance projects; and in the organisation of the main commemorative ceremonies. That process drew on proposed comparisons between national or international remembrance, on firm synergies between the different groups concerned with the remembrance of contemporary conflicts at all levels, and the showcasing of school projects. The process could be pursued while maintaining the underlying movement: bringing together those involved in remembrance (schools, armed forces, organisations, local authorities), offering a clear educational framework that engages students and educational teams around precise projects which “make sense”, and showcasing the educational production – not just as a pretext, but as a key aspect of an assumed remembrance policy. Too many commemorations include “young people” out of the “duty to remember”, without really giving meaning to their involvement.