From witness to historian: a history of commemoration

To commemorate is to remember an event, an act which therefore involves witnesses. Commemorations have always relied, and continue to do so, on the first-hand accounts of those who took part or were victims in conflicts. From the history of first-hand testimonies from the immediate post-war years to the present there emerges a history of commemoration and the construction of remembrance.

2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. The year in which the surrender of Nazi Germany is commemorated began in January with the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by the Red Army, on 27 January 1945. Since 2005, that date has been UN International Holocaust Remembrance Day. In 2020, a great many heads of State and government, among them French president Emmanuel Macron, gathered at the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel, to reflect on the theme of “Remembering the Holocaust, Fighting Antisemitism”. Many ask the question: how can we remember, when the last remaining witnesses, whose role was fundamental in passing on that memory, are no longer with us?

The birth of the witness

How and why did eyewitnesses and their testimonies take up this place at the heart of commemorations? Is it possible to pinpoint the emergence of historical eyewitnesses, if we take that term to mean those who recount what they have seen or experienced? Philippe Lejeune, an expert on all forms of autobiographical writing, points to the shift, in the late 18th century, from the role of the chronicler to that of the witness. The chronicler, usually a low-ranking dignitary, became the established scribe of community life, both locally and nationally. He compiled the information he could gather around him. “Immediate memory” is found in these chronicles, which was intended to be used for the subsequent writing of history. The modern press competed with the chronicle in the 18th century, ultimately killing it off.

The French Revolution signalled the end of the chroniclers and the emergence of a new figure, the eyewitness, in particular the private soldier of the Revolutionary and Imperial Wars, who in principle stuck to what he himself had seen, to his own personal participation in the collective epic. The official birth date of the eyewitness is perhaps Napoleon’s proclamation of 3 December 1805 to the soldiers of the Great Army: “It will be enough for you to say ‘I was at the Battle of Austerlitz’ and people will look at you and say: ‘Now there’s a brave man!’”

Simone Veil and Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier during a televised debate following the screening of the American film Holocaust, 6 March 1979. © Jean-Pierre Courderc/Roger-Viollet

From then on, eyewitnesses were encouraged to say what the press could not say, what only those who had been there could express, about bravery in battle and anguish in the face of disaster. The First World War marked the beginning of testimonies en masse from a fully literate population, together with a focus on this form of writing from researchers like Jean Norton Cru, with his book Témoins (Witnesses), published in 1929. The importance of the testimonial literature of deportation survivors – Resistance fighters or Jews – in the years following the Second World War recalls that which followed the First World War, bearing in mind that the number of deportees – not to mention the number of survivors – was tiny compared with the number of poilus: the former amounted to tens of thousands; the latter, millions. The key difference between the production of the two literatures lay in their reception. Accounts of the Great War were guaranteed to find an audience among the millions of veterans; not so for the deportation survivors in the years following the end of the Second World War, whose number was insufficient to create a real market. The absence of this market, of buyers and readers, partly explains why the production of accounts dried up after 1948. At the same time, there was the absence of a listening ear, which so aggrieved survivors, as emphasised by Simone Veil. Although a comparison can be made between these two mass writing movements, such a comparison is misleading. For it was the genocide of the Jews that raised eyewitnesses to their rightful place, as the tellers of history to build the present-day world. A figure so prominent that it would prompt the rediscovery of accounts of other conflicts or catastrophes, provide an analytical framework for testimony and bring to the fore the witnesses of subsequent genocides, namely that of the Tutsis by the Hutus in Rwanda.

The era of collecting testimonies

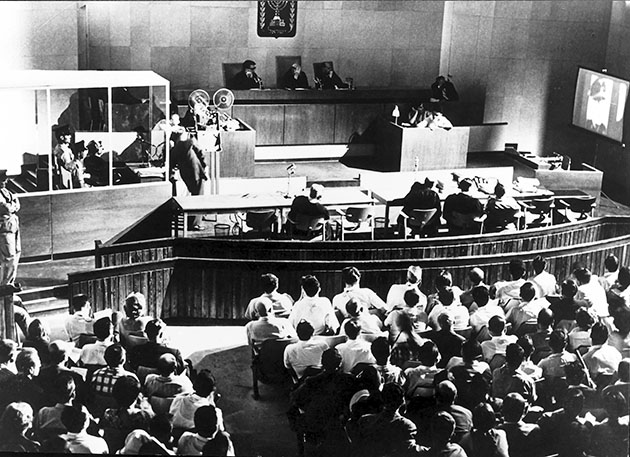

Despite the impressive number of eyewitness accounts published during the Holocaust or in the years that followed, it was the Eichmann trial that marked the advent of the witness. That advent was inherent to the blossoming of the genocide memoir; Jewish to begin with, then American and European. The trial – “the Nuremberg of the Jewish people” (Ben Gurion) – established the genocide as an event distinct from the Second World War. The Israeli prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, opted for a trial based on the testimonies of as many survivors as could be brought to the bar, who told the whole story of persecution and destruction since Hitler’s rise to power. The Eichmann trial for the first time gave survivors back their dignity and made their experience part of history. For the trial was freely and openly filmed for television by the great American documentary filmmaker Leo Hurwitz, and certain accounts had a lasting impact on viewers.

In the late 1970s, the broadcast of the TV series Holocaust in the United States and practically every country in Europe meant the memory of the Jewish genocide was firmly rooted in Western societies. The series also prompted the first major collection of filmed testimonies, begun in 1978-79 at Yale University, New Haven. On seeing the series, a number of survivors who had settled in the town felt it did not reflect their story. They were not assimilated middle-class German Jews like the Weiss family whose story the series told, but survivors of the vanished Yiddish world – “little Jews” from Czechoslovakia, Poland or Romania. They deserved to be able to tell their story. The Yale collection may have been the first, but it was not the last; many others followed. A series of museums, memorials and remembrance organisations put in place their own programmes. The largest in scale was unquestionably that carried out by the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation. Founded by director Steven Spielberg after Schindler’s List, its aim was to gather first-hand testimonies from all the survivors. In the end, it gathered nearly 52 000, in Europe, America, Israel and South Africa. Then the collections stopped. As time passes, the survivors of the Holocaust are becoming fewer. The time has come to make their testimonies available to teachers and researchers, something which the latest technology facilitates.

View of the courtroom during screening of the documentary on the death and mistreatment of concentration-camp prisoners, during the trial of Adolf Eichmann, Jerusalem, 10 June 1961.

© Ullstein Bild/Roger-Viollet

The return of the historian?

Historians had grave misgivings about these testimonies. Such misgivings have since transformed into a genuine passion. Christopher Browning’s book is a good example. With Remembering Survival: Inside a Nazi Slave-Labor Camp, he rises to the challenge of writing the history of the Starachowice camp based almost exclusively on first-hand accounts. No study had ever been carried out before on these labour camps for Jews. Of course, Browning knows the accounts are not always reliable, being influenced by all that the witness has seen and heard since the war. But, as a veteran of archival research, he explains, you develop “a very subjective form of intuition”, which helps you appreciate the authenticity and reliability of testimonies. In addition, the historian distinguishes very clearly between places that have been in the media spotlight – due to first-hand testimonies, documentaries, fictional accounts, in particular Auschwitz – and those never previously seen in the public domain. Concerning the former, “stereotyped formulas” are used and “iconic images” are slipped into the accounts, largely derived from films like Holocaust or Schindler’s List.

On Auschwitz, the same themes are taken up: many today tell of how they passed through the gate bearing the words Arbeit macht frei on entering Birkenau, when that gate is actually at Auschwitz I. Yet it has been shown so often in cinemas. Many also recount the “selection” process upon entry to the camp or in the blocks by a doctor who is unmistakably Dr Mengele, as if he had been on duty 24 hours a day on the arrival ramp and in the camp. Others had experiences which they had never talked about in full before, and which had not been in the media or been interfered with by other accounts, books or films. Such testimonies are as if “encapsulated”, and have remained intact. These are of particular interest to historians studying little-known aspects of the persecution. So you could say the reliability of late testimonies depends on what the person witnessed.

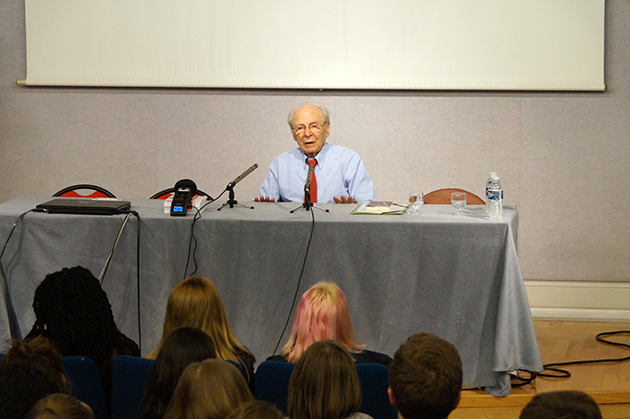

Henri Borlant, a Holocaust survivor and author of Merci d’avoir survécu, gives a talk to final-year students in Metz, 29 March 2018. © La Rédaction

Testimonies as a source

Yet it is clear not only from analysing the production of first-hand accounts, whether in the form of written accounts or recordings, that the era of the testimony is upon us. It is apparent, too, in the role assigned to surviving eyewitnesses to tell and retell their stories as much as they can to educate young people. It is closely bound up with the development of our societies and of the discipline of history. The end of communism signalled the end of the great models to explain world history. It saw the blossoming of what some call “history from below”. Major events are no longer analysed in a temporal perspective; instead, the focus is on the impact they have on people. If the “era of the witness”, in the strict sense of the term, is coming to an end – with the inevitable deaths of the last remaining Holocaust survivors – in a broader sense it goes on flourishing. Having the chance to speak and tell one’s own story is the very essence of the movement.

This place assigned to witnesses says much about the times we are living in. It sets store by subjective opinions and is characterised by what François Hartog calls “presentism”, which Olivier Rolin describes in his novel Paper Tiger. In his youth in the 1960s, “it was as if the world out there, where you lived, became more profound, transfigured by a power that linked each event, each individual to an age-old chain of greater, more tragic events and individuals. (...) Today it seems there’s only the present, just the instant; the present has become a colossal hustle and bustle, one big stimulus, a permanent big bang”.

It is up to historians to always keep in mind the need to establish the veracity of events; to attempt to make those events intelligible by keeping a distance from the emotion that emanates from a witness’s words. Nazism, for example, and more specifically the Holocaust, is not limited to the suffering of those who survived it.

Testimonies – the accounts given by witnesses in various forms – are certainly a source for historical writing or a means of raising awareness about the past. But by overstating the importance of witnesses and the uses made of them today, we run the risk of forgetting the history.