The Battle of Glières

Sous-titre

31 January - 26 March 1944

From late 1942, many young Frenchmen who objected to being sent on compulsory labour service to Germany took refuge on the Glières Plateau, near Annecy, Haute-Savoie, 1500 metres above sea level.

The Glières Plateau. Source: Association Haute-Savoie Nordic

The Mouvements Unis de la Résistance (MUR) organised them into groups and gave them military training. Despite the repression and a lack of resources, these rural guerrilla groups, or maquis, grew in number over the summer of 1943.

Commander Romans-Petit (organiser of the Armée Secrète (AS) in Ain and head of the AS in Haute-Savoie from November 1943 to February 1944) set up an officer training school at Manigod in the Massif des Bornes, near the Glières Plateau.

Maquisards. Source: Conseil Général de la Haute-Savoie.

To disrupt the enemy during the Allied landings, the Armée Secrète needed weapons. A reconnaissance mission was sent from London to identify potential parachute landing sites in the area. In fact, its main task was to assess the maquis’s capabilities, and it had difficulty asserting its authority over the already well-organised local Resistance.

Parachute drop. Source: Photo by Raymond Perrillat. Conseil Général de la Haute-Savoie / Fonds Association des Glières.

The mission consisted of the British lieutenant-colonel Heslop (Xavier) and the French captain Rosenthal (Cantinier). Of the areas examined, it was the Glières Plateau that was chosen. This vast mountain pasture was relatively isolated, with large, fairly level grassy areas some distance from the high summits, and was easily visible from the air due to its alignment with Lake Annecy.

Parachute drop. Source: Photo by Raymond Perrillat. Conseil Général de la Haute-Savoie / Fonds Association des Glières.

In late January 1944, Romans-Petit entrusted the maquis command to Lieutenant Tom Morel. His mission was to receive the parachute drops promised by the British with a hundred men.

Tom Morel. Source: Photo by Raymond Perrillat. Conseil Général de la Haute-Savoie / Fonds Association des Glières.

On 6 February 1944, he had to leave for Ain, where his maquis were being attacked by the Germans, and he left the department under the responsibility of Captain Clair, assisted by Cantinier as liaison officer with London. Two days later, at a meeting in Annecy, it was decided to assemble as many maquisards as possible on the plateau in order to establish a base from which to attack the Germans. The goal was to show the Allies that the Resistance, under General de Gaulle, was capable of large-scale operations.

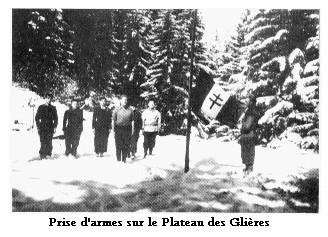

Military parade on the Glières Plateau. Source: Union Française des Associations de Combattants de Bagnolet.

In late January 1944, 467 maquisards led by Lieutenant Morel climbed up onto the Glières Plateau to establish a veritable entrenched bastion that would provide protection for a reception site deemed ideal for the airborne operations,

London, which planned to set up large “enclaves” to hold the German troops there for the future landings, promised to parachute in weapons, equipment and a battalion of British soldiers. But very soon, the plateau was surrounded by the Germans. No help arrived. On 9 March, the maquisards’ leader, Lieutenant Morel, was killed by an officer of Vichy’s Mobile Reserve Groups (GMRs). Morel was replaced by Captain Anjot.

Morette Cemetery, 18 October 1944: Roger Cerri (third from the right) bears the coffin of Captain Anjot, preceded by that of Lieutenant Dancet and followed by that of Sergeant Vitipon. Source: Alain Cerri.

Morel’s funeral. Source: Photo by Raymond Perrillat. Conseil Général de la Haute-Savoie / Fonds Association des Glières.

Joseph Darnand mobilised militiamen and GMRs, which surrounded the plateau. On 20 March, supported by air force and artillery, a Wehrmacht mountain division of 6 700 men, together with members of the Garde Mobile, GMRs and militia (in all, over 2 000 Frenchmen, led by General Marion and Colonel Lelong) launched the attack.

German attack. Source: Photo by Raymond Perrillat. Conseil Général de la Haute-Savoie / Fonds Association des Glières.

On 27 March, after a week of difficult fighting in the cold and snow, without heavy weapons, bombarded by the Luftwaffe and artillery, the maquisards were forced to give in. They left 155 dead and 30 missing. One hundred and sixty were taken prisoner. Most of them were tortured, then executed by firing squad or deported.

The event received a great deal of coverage in the war of the airwaves, and the Resistance gradually regained control of the department.

On 1 August, a further mass parachute drop was carried out. Several tonnes of weapons were recovered and distributed to more than 3 000 Resistance fighters. The fighting for liberation in the department began on 16 August.

On the 19th, the German troops surrendered to the maquisards, without waiting for the arrival of the Allied troops, who had not yet reached Grenoble.

De Gaulle at Glières. Source: Alain Cerri.

On 5 November 1944, General de Gaulle, the head of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, visited the Morette Cemetery to honour the combatants of Glières and the population who supported them. He said: “It is thanks to Glières that I was able to make mass parachute drops for the Resistance.” From then on, the plateau was given the place it deserved in French history.

André Malraux unveils the monument. Source: Photo by Raymond Perrillat. Conseil Général de la Haute-Savoie / Fonds Association des Glières.

On 2 September 1973, Émile Gilioli’s National Monument to the Resistance was unveiled by André Malraux.

The monument. Source: Photo by Gérard Métral / Association des Glières.

Key dates:

31 January 1944: Arrival of three AS camps (around 120 men) on the plateau, under the protection of paramilitaries from Thônes.

5 February: Operations are triggered by a roundup by the Milice in Thônes, who engage with the paramilitaries.

7 February: In Essert, members of the Garde Mobile open fire without warning on a six-man supply unit and take three maquisards prisoner.

12 February: Once again in Essert, a large Garde Mobile detachment on reconnaissance falls into an ambush: two are killed, six wounded (two mortally), three taken prisoner. No maquis losses.

13 February: The plateau is completely surrounded by the security forces.

14 February: First parachute drop: 54 containers.

2 March: Punitive expedition against the GMRs stationed at Saint-Jean-de-Sixt.

5 March: Second parachute drop: 30 containers.

7 March: The Garde Mobile is relieved by the GMRs.

8 March: Engagements with the Milice on reconnaissance at the Col du Freu and Les Collets: one militiaman is mortally wounded.

9 to 10 March: “Coup de main” attack against GMRs stationed at Entremont: two policemen are killed (one is Commander Lefèvre), three wounded and 60 taken prisoner. Two maquisards are shot died (one is Lieutenant Tom Morel), three are wounded (one mortally).

10 March: In retaliation, the GMRs attack towards Notre-Dame-des-Neiges and fall into an ambush: ten prisoners taken. Overnight, a third parachute drop is made: around 250 containers.

12 March: Three Heinkel 111s drop around a hundred 50 kg bombs, which destroy a few chalets.

17 March: The Heinkels return to bomb Col des Auges, the highest position.

18 March: The Milice relieve the GMRs on the front line.

20 March: Attack by militiamen on La Rosière and Col de Landron. Four maquisards on patrol are shot dead.

22 March: Engagement with militiamen at Col du Freu.

23 March: Four Focke Wulf 190s machine-gun the Plaine de Dran: four maquisards are wounded (one mortally and one seriously) and several chalets are burnt.

24 March: The Wehrmacht takes up position at the foot of the plateau. At Col de la Buffaz, militiamen lay an ambush for a group of six maquisards: one maquisard is killed and one seriously wounded, but one militiaman is seriously hit and another is taken prisoner.

25 March: Aerial bombardment of the plateau and artillery bombardment of Monthiévret.

26 March: In the morning, aircraft set fire to the last chalets and detonate the munitions depot.

Attack by militiamen on Col de l’Enclave is pushed back: two killed, two wounded, four missing. No maquis losses. Attack by the Germans on Lavouillon is pushed back: possibly two or three wounded on their side. No maquis losses. In the evening, attack and breakthrough by the Germans at Monthiévret: possibly two or three wounded. On the maquis side, two killed and several wounded (one seriously). That night, the order is given to desist.

27 March: Ambush at Nâves: six maquisards killed (including Captain Anjot). Ambush at Morette: a dozen maquisards killed. Ambush at Thorens: two maquisards killed.

N.B. By secret message no 1363/44 of 28 March, General Pflaum, commander of the German forces, notified his superior that his own losses had been two NCOs and two men badly wounded, while enemy losses had been 89 prisoners and 35 dead (the Germans having finished off the three seriously wounded maquisards).

Over the following days, maquisards and “standby” fighters would be shot dead or executed by firing squad by the Wehrmacht and, to a lesser extent, the Milice.