Battles of Saint-Marcel

Sous-titre

June 1944

The battles in Saint-Marcel marked an important turn of events in Brittany's Resistance movement.

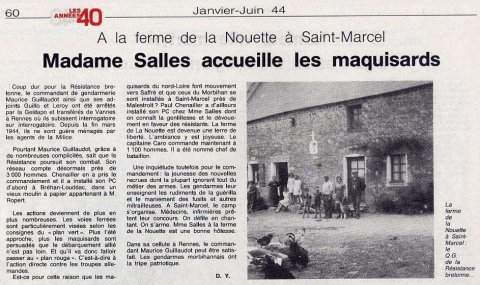

Not far from Vannes, at the western fringes of the village of Saint-Marcel, La Nouette farm was chosen as the landing site for paratroopers and equipment sent by the Free French air operations bureau to the Morbihan Resistance. The operation was codenamed ”Baleine” (whale in French). The first and only parachute landing before the fighting in 1944 was made in May 1943.

However, in late 1943, this area of land was chosen by the departmental head of France's Secret Army to receive arms and reinforcements to be parachuted in at the time of the future landing. A small group of resistance fighters was stationed around the camp.

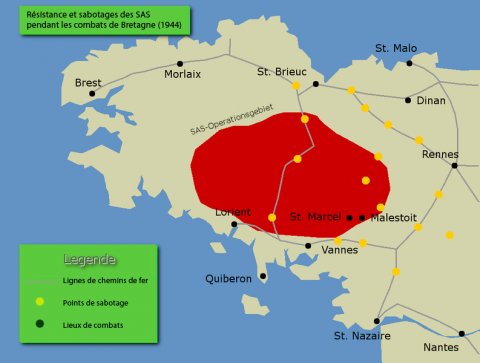

Operation zones of the SAS and the resistance movements (maquis) in Brittany. Source: GNU Free Documentation License.

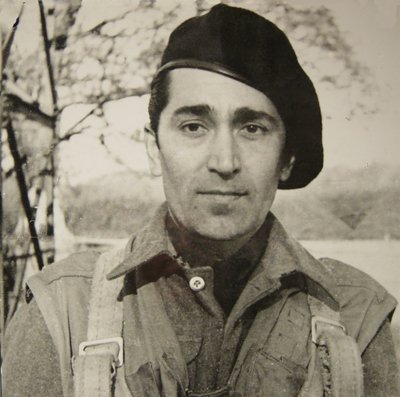

Paul Chanaillier, alias Colonel Morice. Source: DR

During the night of 5 June 1944, at the same time as the first British and American troops were flown into Normandy, the first paratroopers landed in Brittany.

At the door of a C-47 Dakota airplane, a French paratrooper of the SAS (Special Air Service) French Squadron is ready to jump. At his feet is the bag containing his equipment. Source: ECPAD

They were part of the Free French paratroopers, who depended on the SAS (Special Airborne Service), the 2nd Parachutist 'Hunters' Regiment who had already earned itself a reputation for victory, notably as part of the British 8th Army during the Libya Campaign in 1942 and 1943. This unit was led by Colonel Bourgoin.

Colonel Bourgoin. Source: Musée de l'Ordre de la Libération

The paratroopers had a twofold mission: to carry out sabotage operations to cut off the Breton peninsula and block the route for transporting German reinforcements to the landing sites and to infiltrate Brittany and set up bases to receive parachute and airborne units. Thus two precursory detachments were dropped onto the northern coasts and into Morbihan to investigate the enemy forces and the defensive opportunities in cooperation with the Resistance, with the intention of setting up home base for future operations.

Likewise, in Morbihan, Lieutenant Marienne's group was parachuted in to Plumelec and Lieutenant Deplante's near Guéhenno. Marienne's group came under heavy attack by the German garrison in Plumelec and lost one man, Corporal Bouëtard from Brittany, the first allied soldier killed in the Liberation battles. Three radios and transmission equipment were captured by the enemy.

Lieutenant Marienne. Source: DR

On 6 June, the local and departmental Resistance leaders all met at the camp in La Nouette. Some maquisards (rural guerrilla bands) also came, joined on 7 June by many volonteers including a notable number of women and paratroopers including lieutenants Marienne and Deplante.

1940s retrospective. Source: Ouest France

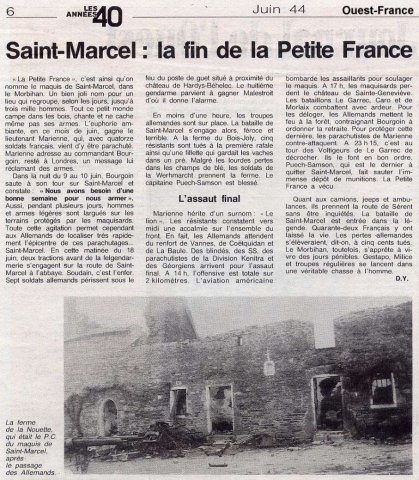

1940s retrospective. Source: Ouest France

In Saint-Marcel and the surrounding towns and villages, the maquisards were hunted and the populations terrorised. The brutalities increased and summary executions took place, mainly of several resistance fighters and paratroopers but also of civilians. On 25 and 27 June the chateaux of Sainte-Geneviève and Hardys-Béhélec were burned down and what remained of the farms and the town of Saint Marcel was destroyed.

German forces interrogating the inhabitants of a Breton village suspected of being terrorists. July 1944. Source: German Federal Archive