Chantiers de la jeunesse

With the armistice agreement that took effect on 25 June, nearly 100,000 young men who had just been drafted found themselves demobilised and left to their own devices. On 31 July 1940, Vichy issued a decree creating the ”Chantiers de la Jeunesse”: ”Article 1: the young men enlisted on 8 and 9 June 1940 are relieved of their active military obligations by the present decree. Article 2: from said date, they are assigned for six months to youth groups set up under the authority of the Ministry of Youth and the Family”. This new structure was put under the orders of General de La Porte du Theil, a former scout leader.

General de la Porte Du Theil, head of the Chantiers de Jeunesse (A. D. Allier, 69 J 130, Crépin Leblond collection). Source: A. D. Allier

For General de la Porte du Theil, it was not enough just to house and occupy these young recruits, they had to be actively prepared for the ”renewal” of Maréchal Pétain's France. These young people represented a large force which, if organised and trained, would be able to provide the new regime with a solid base. The guidelines for the Chantiers de la Jeunesse were quickly laid down as part of the National Revolution: an education respecting traditional values, renewed value placed on manual labour without neglecting intellectual and cultural activities, etc.

Chantiers de Jeunesse poster, 1941. Drawn by Eric Castel, published by the State Secretariat for Information. (A. D. Allier, Fi, unlisted, furnishing 16). Source: A. D. Allier

At each of the 52 camps set up with between 1,500 and 2,200 young people each, the day began with the raising of the flag in a solemn ceremony.

Saluting the flag at a Chantier de Jeunesse (A. D. Allier, 69 J 134, Crépin Leblond collection). Source: A. D. Allier

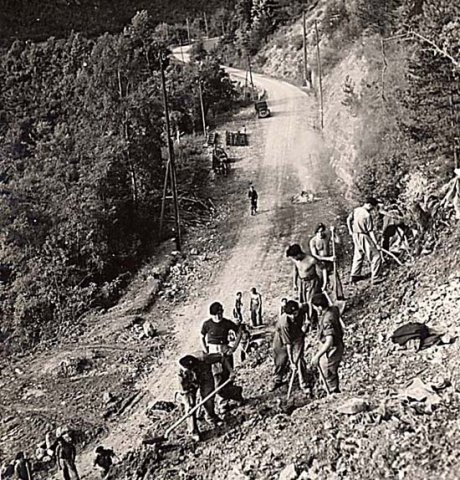

The day was divided into two parts - on the one hand there was work at the worksites, on the other, physical education and technical instruction. The work was first and foremost an educational tool. The aim was to work together to produce something useful for the country without any consideration for profitability: supplying firewood and charcoal, building paths and trails, an introduction to wood and iron work, masonry, etc. There was military discipline, with limited leave granted for cities considered as ”temptresses”.

Earthwork at the Chantiers de Jeunesse (A. D. Allier, 69 J 93, Crépin Leblond collection). Source: A. D. Allier

The young people at the worksites needed ”leaders”. They were chosen from the graduates of the Officer Candidate School. This selection naturally gave a paramilitary character to the worksites. A worksite supervisor school was created and was definitively housed at the Château de Bayard in Uriage.

The Château d'Uriage was home to the École des cadres de la Jeunesse as of the beginning of 1941. Source: Licence Creative Commons

Uriage had two functions: firstly, in the context of a military debacle, the collaborationist government sought to maintain order by preventing all attempts at taking up an armed struggle. Thus, the Chantiers de la Jeunesse, backed up by Uriage, took charge of the demobilised young men. Secondly, the supervisor school was supposed to serve as an ideological laboratory.

The training sessions were a way of selecting young leaders who, depending on their merits and especially their loyalty to the ”Maréchal”, were assigned to command positions. Their explicit purpose was to pacify the demobilised soldiers. They learned to march, they wore uniforms, but they did not carry weapons. The ”entraide nationale des jeunes” (national youth mutual assistance) was a way of keeping an eye on them and coordinating them to avoid having them take up arms against the occupying power.

Ordered by the Germans to be closed at the beginning of 1943, most of its members joined the French resistance.

The Germans had never approved of the training given to these young reservists in the rear. They therefore set up close surveillance of the young men's activities and forbade the expansion of the worksites to the occupied zone.

In January 1941, the training session at the worksites was made mandatory for all 20-year-old men and its duration was extended to eight months.

After the Anglo-American landing in North Africa on 8 November 1942, Regional Commissioner Van Hecke provided the new French Army fighting against Germany in Tunisia with 40,000 young men from the Chantiers de Jeunesse in French North Africa. He himself became the head of the 7th Chasseurs d'Afrique regiment, which served gloriously in Italy and in 1944 during liberation of France and then in Germany in 1945.

After the Germans invaded the free zone of France on 11 November, mistrust of the occupant increased. At the beginning of 1943, the Compulsory Work Service in Germany, set up by Pierre Laval, marked the end of the worksites, which appeared as a perfect, large source of workers. General de la Porte du Theil, who refused to call on the young men to join the maquis, nonetheless resisted sending thousands of Frenchmen to Germany. He was revoked, arrested and deported to Germany. On 19 January, the worksites were put under the authority of the Ministry of Labour. At the worksites, resistance to Compulsory Work Service intensified and many of the young men joined the maquis.

Trained to have unquestioned obedience to Maréchal Pétain, a large number of the young people at the worksites nonetheless joined the French maquis in January 1943. Many of them were armed in the Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur, at Glières and Vercors, then joined the French 1st Army under General de Lattre de Tassigny, where the young men from the French North Africa worksites were already fighting.