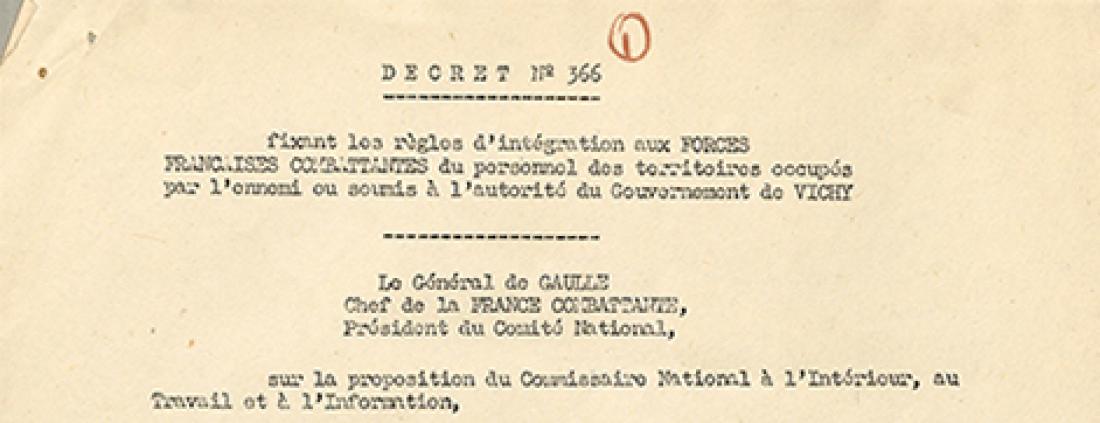

Decree 366 of 25 July 1942

Free France produced its own laws, carrying out fundamental legal work that was confirmed following the Liberation and whose traces still remain in today's substantive law. This is the case with ”decree 366”: signed in London on 25 July 1942, this text, which sets the rules by which people can join the Free French Forces, is still valid and continues to have an impact. As for the note on the application of the decree, it gave rise to several particularly moving chirographs.

Evoking the legal work of Free France means paying tribute to its legal experts, starting with René Cassin. Arriving in London on 28 June 1940, Cassin was received by General de Gaulle the following day and immediately put in charge of organising the legal services necessary for France's recovery. A pacifist former soldier, a professor in the Paris law faculty and France's delegate to the League of Nations for fourteen years, he was an experienced lawyer whose expertise was well known. As well as founding these legal services, René Cassin was entrusted with the task of negotiating the first agreements with Churchill and defining the status of the French volunteers arriving in England to continue the fight. This committed intellectual, steeped in rigour and integrity, was also the author of many acts of recognition, bilateral agreements, diplomatic memos, orders and decrees.

Little by little, by increasing its numbers and incorporating new skills, expanding its services and diversifying its activities, Free France managed to acquire the attributes of a public power. An analysis of decree 366 illustrates this.

A fundamental text

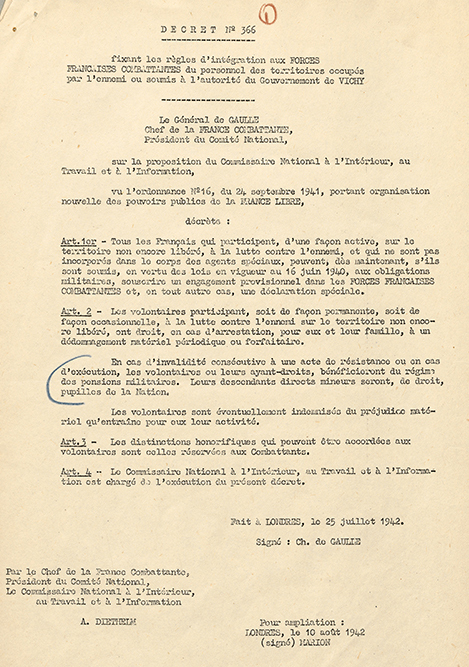

Promulgated in London on 25 July 1942, and introduced clandestinely into occupied France for the heads of the resistance networks, decree 366 (see slideshow) is a fundamental text that sets the rules for joining the French Fighting Forces (FFC). Nevertheless, the decree, signed by Charles de Gaulle, the leader of Fighting France and President of the National Committee, was little known by historians and the general public for many years, as was the subsequent note or circular of application no. 1368/D/BCRA, dated 27 July 1942. It is doubtless due to this general lack of knowledge that reading the files relating to the FFC networks from the Resistance Bureau sometimes disappoints certain readers, particularly if they stumble on categories O, P1 and P2, the assimilation ranks and the notion of agent, whose full meaning and scope they struggle to understand.

In order to gain a better knowledge of these two texts, it should be pointed out that they can now be consulted easily on the Internet. Never withdrawn, they remain in force and continue to have an impact. They play a role in France's law on pensions for military invalids and war victims and in the official armed forces bulletin.

Note 1368/D/BCRA

Incorporating volunteers into the FFC required individual files to be maintained in London. But how could these files be created when the volunteers themselves had no direct contact with Free France's services in London, when they used and abused pseudonyms in the field, when they avoided conserving papers which would have exposed them to the most terrible dangers? More importantly, when peace was restored, they might need to demonstrate that they were officially enlisted. How could they prove that they belonged to the network, in order, for example, to benefit from the certification of services completed or obtain the compensation and pensions provided for by the decree in the event of harm, arrest, invalidity or death resulting from acts of resistance?

Free France's jurists dealt with these points in detail in the note or circular 1368/D/BCRA. Doubtless these legal and administrative concerns resulted in comments of varying degrees of acerbity from Resistance members on the ground, who were hoping for weapons rather than legal texts. But, equally doubtless, they also helped to motivate their companions and comrades, especially those who wanted to know what tomorrow would bring for their nearest and dearest if the worst happened to them. The provisions of decree 366 were respected: military invalidity pensions are still paid today on the same basis, mainly to internees and deportees, including to surviving spouses, because these pensions are transmissible and reversible.

Clandestine enlistment in the FFC

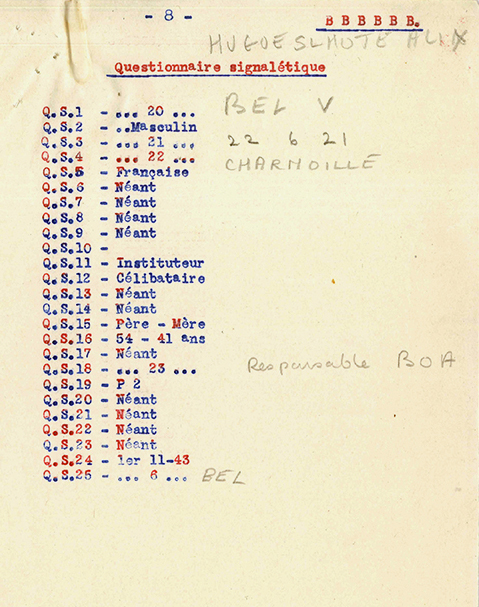

Enlistment in the FFC depended on conditions relating to both form and substance. It required a meeting in the field between the commander and the volunteer, during which the commander asked the volunteer to ”recognise General de Gaulle and the French National Committee as the only representatives of the fighting French and to declare a commitment to serving with honour, loyalty and discipline in the FFC”. Following this, the commander received the enlistment deed and completed the identity questionnaire (QS or questionnaire signalétique, see slideshow).

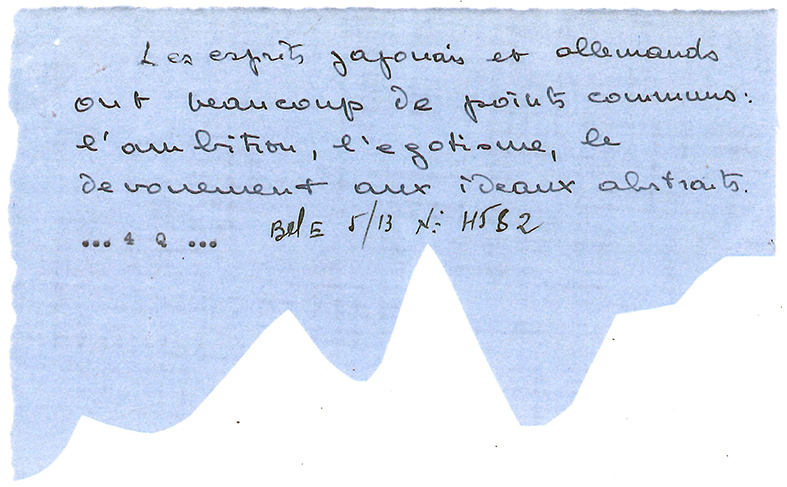

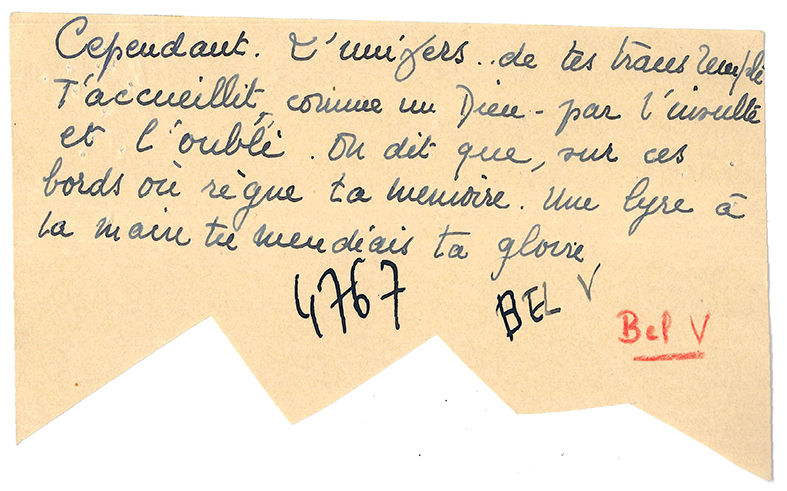

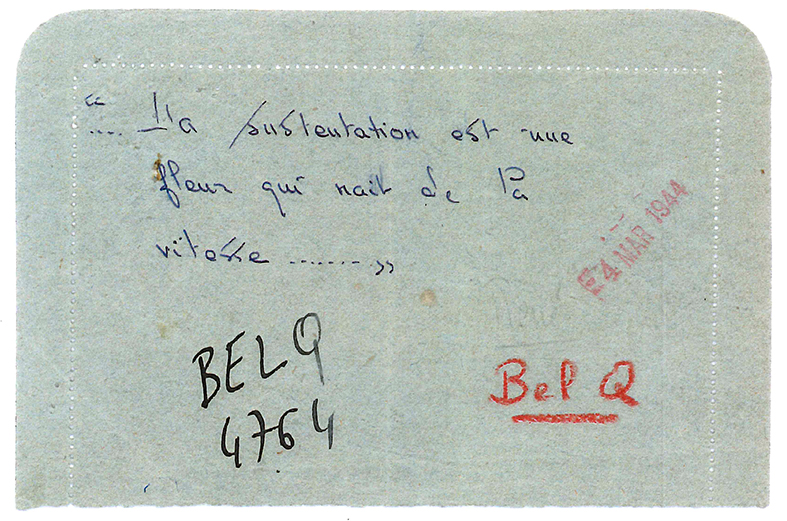

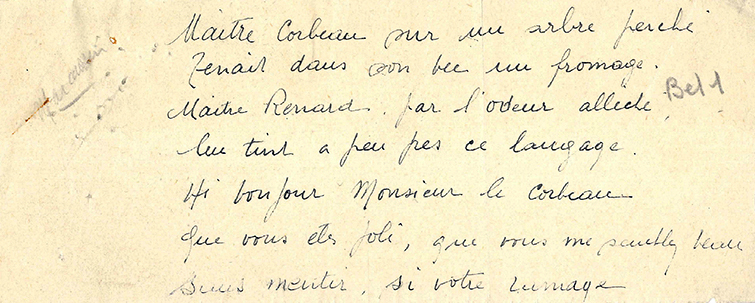

The FFC enlistment deed was a handwritten note anyone can read but only initiates can understand. The volunteer was asked to take a sheet of paper and write out by hand a few lines of text, preferably trivial, chosen by the volunteer. He was then told to cut the sheet in two in a zigzag shape, or cut through the middle of the text, giving the top half to the commander and keeping the lower half. The purpose of this procedure was to identify the volunteer discreetly, as bringing the two halves together proved his enlistment. In future years, anyone who could provide the lower half of a small piece of paper to the representative of an administration that held the upper half, thus making the truncated text intelligible, could legitimately claim the benefit of the advantages specified in articles 2 and 3 of decree 366. A document of this type is known as a chirograph.

The QS, meanwhile, was a set of 25 useful questions for opening large numbers of individual files. The standard questionnaire is reproduced in the official armed forces bulletin.

Protecting agents

Once these formalities were complete, it was up to the commander to transfer the documents to London quickly. For obvious security reasons, he was asked to send the upper half of the enlistment deed and the QS separately, e.g. sending batches of enlistment deeds by post and QS by radio. Or, if both enlistment deeds and QS were on paper, two separate clandestine air operations could be used. Naturally the QS would be encrypted, at least partially, which was essential for sensitive responses. As the commander would sometimes quote the volunteer's code on the deed and the QS, he would have to send to London a list of codes with the corresponding identities, ideally separately. The volunteer's code consisted of the prefix allocated to the network followed by a number allocated in sequence.

When the documents were received in London, the relevant sections of the Bureau central de renseignements et d'action (BCRA, Central Bureau of Intelligence and Operations) would open a file for each volunteer. The files were ordinary cardboard document wallets bearing the agent's BCRA registration number and code, or perhaps a fictional identity. The first documents filed were often the QS, enlistment deed and identifying texts.

Finding and identifying volunteers

It was a joy for subsequent researchers to open these 18,000 files and consider these enlistment deeds and identity questionnaires and everything they represent, trying to identify their authors and the people described. But there were also files that could not be found, either because they were lost en route or because the events of the war and the violence of the repression imposed other priorities. Moreover, not all the networks' agents belonged to the FFC and the staff of General de Gaulle. Ultimately, the disappointment of a vain search should not obscure the fact that there were other methods of enlistment: by proxy, with a declaration sent by cable or with a form completed in London. Not to mention retrospective registrations, of greater or lesser validity.

A systematic analysis of about 1,500 of these files has revealed that the recommendations in the decree and its note of application certainly had an impact, more in some networks than others, but it is too early to be able to draw authoritative conclusions here. The selection of chirographs presented in these pages is dedicated to the memory of the agents of the Bureau des opérations aériennes (BOA, Air Operations Bureau). This major operational network responsible for clandestine air operations in the northern zone was created in spring 1943 under the authority of Jean Moulin, with pioneering support from Jean Ayral (Pal), Paul Schmidt (Kim), Michel Pichard (Bel) and Pierre Deshayes (Rod).

We see that the code Bel is often quoted. Like the code Gauss that followed it, this refers to Michel Pichard, commander of the BOA eastern bloc and national coordinator. Each regional commander had authority over a district commander, who in turn was close to the sector commanders.

The enlistment deeds, QS and texts presented here allow us to identify:

• Bel-V (see slideshow), alias Alix Lhote, born 26 June 1921 in Charmoille (Doubs), teacher and sector commander. Arrested on 3 April 1944. Deported to Natzweiler-Struthof and Schömberg.

• Bel-Q (see slideshow), alias René Pajot, born 22 February 1918 in Saint-Vénérand (Haute-Loire), operations officer in Haute-Marne. Arrested on 10 February 1944 in Dijon. Deported to Neuengamme.

• Bel-1 (see slideshow), alias René Collin, born 4 June 1922 in Saint-Cloud, operations officer in Marne, Meuse, Meurthe-et-Moselle and Vosges. Arrested on 24 April 1944 in the region of Longwy. Died after deportation to Melk.

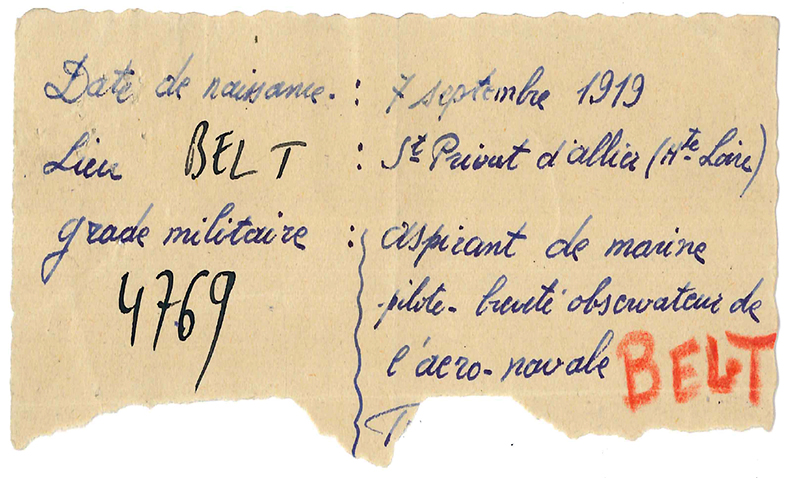

• Bel-T (see slideshow), alias Roger Ramey, born 7 September 1919 in Saint-Privat-d'Allier (Haute-Loire), district commander in Côte-d'Or. Arrested on 9 March 1944 in Dijon. Died after deportation to Gusen.

• Bel E (see slideshow), alias Roger Lebon, born 5 November 1924 in Paris, eastern bloc liaison commander. Arrested on 20 March 1944 in Rue de Lourmel, Paris. Deported to Dachau.

Michel Blondan

Retired teacher. Doctor of law specialising in the history of the law and institutions.

Author of two books on the customs of Saint-Claude.

His current research covers the Bureau des opérations aériennes, region D.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Decree 366 and the circular of application can be consulted in the official armed forces bulletin (see Bibliography and sitography). The enlistment deeds of FFC agents are conserved in nearly 18,000 individual files in alphabetical order, usually by pseudonym but sometimes under the agent's real name. These archives will constitute sub-series GR 28 P 11.

Décret n°366 du 25 juillet 1942.

© SHD

Acte d'engagement de Bel-V, alias Alix Lhote, 1943.

© SHD

Questionnaire signalétique de Bel-V, alias Alix Lhote, 1943.

© SHD

Acte d'engagement de Bel-Q, alias René Pajot, 1943.

© SHD

Acte d'engagement de Bel-1, alias René Collin, 1943.

© SHD

Acte d'engagement de Bel-T, alias Roger Ramey, 1943.

© SHD