Rallying the Empire to Free France

Sous-titre

1940

Following General de Gaulle’s call to arms of 18 June 1940, volunteers keen to join Britain and Free France began streaming in, but the British attack on the French fleet at Mers el-Kébir, for fear that the vessels should fall into German hands, dealt a serious blow to recruitment. In early July, Free France amounted to no more than a handful of exiles, dependent on British support.

History

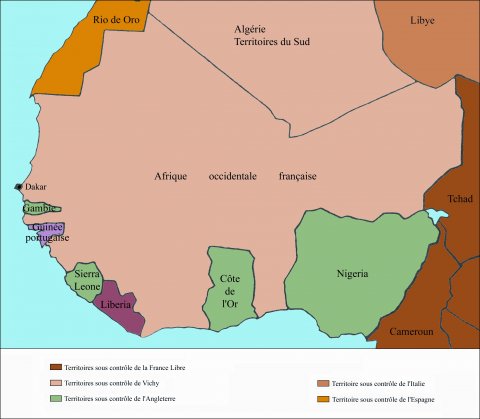

French possessions in Africa in late 1940. © MINDEF/SGA/DMPA/Joëlle Rosello

The challenges of rallying the French imperial territories to Free France were many. In order to find its place and exert some influence among the Allies, Free France needed a territorial base. Metropolitan France may for now have been under the occupier’s jackboot, but it had vast overseas territories. Strategically, they could serve as Allied bases from which to continue the war.

Despite promising signs, however, the imperial territories did not rally to the cause. Their leaders remained loyal to Vichy and did not follow through on their initial desire to carry on the fight. Few overseas territories rallied spontaneously to Free France in 1940. Barring a few exceptions, it was a decisive external rather than internal action that prompted them to switch to the Free French side.

The New Hebrides, a Franco-British condominium in the Pacific, paved the way. It was followed by Tahiti, the French Establishments in Oceania, the five trading posts of the French East India Company (Pondicherry, Mahe, Karikal, Chandernagor and Yanaon), and finally New Caledonia. Their strategic interest would be revealed a year later when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

General de Gaulle at Douala in October 1940. Source: Rights reserved

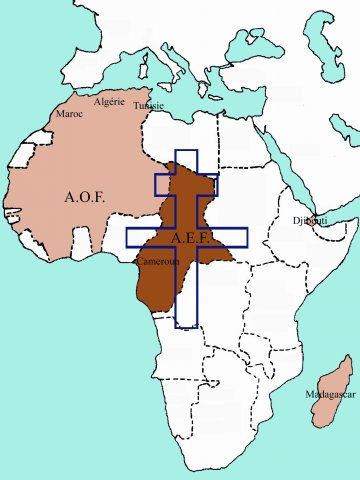

For the moment, the stakes in Africa were of a wholly different significance. Its human potential and geographical location meant that Africa could be the base for a reconquest of France and Europe. Whereas General de Gaulle initially planned to focus his efforts on Dakar and West Africa, when Chad came on side, influenced by its governor Félix Éboué and military leader Colonel Marchand, de Gaulle rethought his initial intentions. The consequences of Chad joining Free France are far from negligible.

The Richelieu firing off Dakar, September 1940. Source: Rights reserved

Chad’s long border with Italian Libya meant that the Free French Forces found themselves in direct contact with the enemy and close to their British allies stationed in Egypt. Operations were therefore launched in Equatorial Africa, particularly since messages and telegrams gave the impression that Free France found favour everywhere. That impetus was nevertheless subject to pressures from Vichy. They therefore had to act quickly. General de Gaulle dispatched Leclerc and Boislambert to Cameroon, which they persuaded to come on side, thanks to support from groups favourable to the Free French cause. Almost simultaneously, Colonel de Larminat persuaded to Middle Congo to rally, despite resistance from General Husson, commander of the troops and governor-general, while Ubangi-Shari, persuaded by the governor of Saint-Mart, followed suit. In Equatorial Africa, only Gabon could not be moved, remaining loyal to Vichy.

Félix Éboué and the governor of New Caledonia and the New Hebrides, Henri Sautot – Musée de l’Ordre de la Libération collection

To provide Free France with a broader political, territorial and financial base, it was now necessary to move on to the next step: the rallying of French West Africa. As hopes of a chain reaction in French West Africa faded following the failed enterprise in Gabon, the chosen plan of action was a joint Anglo-French operation on Dakar. Not having managed to bring Governor-General Boisson on side by peaceful means, the Gaullists tried in vain to land in the Bay of Rufisque. The British then decided to deploy their own forces, but did not succeed in breaking through the resistance of the Vichyist forces. The operation was a failure. Hopes were dashed of the Empire rallying swiftly and completely to the Free French cause.

French West Africa in December 1940. © MINDEF/SGA/DMPA/Joëlle Rosello

Click on the image to open it

In Autumn 1940, General de Gaulle would turn his full attention to Gabon. Surrounded on all sides by French Equatorial Africa, Gabon could indeed represent a threat, or at least a hindrance, to the Allies. Simultaneous offensives were launched against Libreville and Port Gentil. The Gaullist troops were met by stiff resistance. Their progress was slow and difficult. It was only after violent fighting that Gabon was finally overcome.

French Equatorial Africa and Cameroon in December 1940. © MINDEF/SGA/DMPA/Joëlle Rosello

Click on the image to open it

Despite the failure in Dakar, General de Gaulle now found himself with territories to govern. While the fate of Gabon was still being decided, he set up, from Brazzaville, on French soil, Free France’s very first government body: the Conseil de Défense de l’Empire, or “Empire Defence Council”. It was responsible “for the overall conduct of the war, in all spheres, towards liberating France and, in conjunction with the foreign powers, the handling of all matters concerning the defence of French possessions and French interests [...]”. From now on, Free France had a political apparatus to ensure it the beginnings of representation. After its victory in Gabon, it controlled the whole of French Equatorial Africa. General de Gaulle could now finalise his military and administrative organisation. He reallocated responsibilities and appointed new governors to the newly allied territories. General de Larminat became high commissioner of the African territories of Free France, Félix Éboué governor-general of Equatorial Africa, Pierre-Olivier Lapie governor of Chad, Lieutenant-Colonel Parant governor of Gabon. Pierre Cournarie was appointed governor of Cameroon, while Colonel Leclerc took over the command of the Chad troops. Pierre de Saint-Mart remained governor of Ubangi-Shari.

Key dates:

17 June 1940: France requests an armistice; General de Gaulle leaves for London.

18 June 1940: General de Gaulle issues his call to arms.

22 June 1940: Franco-German armistice signed at Rethondes.

24 June 1940: Franco-Italian armistice signed in Rome.

25 June 1940: The French government sets up a high commission for French Africa.

28 June 1940: General de Gaulle is recognised by Great Britain as the leader of the Free French.

2 July 1940: The French government is installed in Vichy.

3 July 1940: Britain attacks the French fleet at Mers el-Kébir.

8 July 1940: The Richelieu is torpedoed by the British in Dakar harbour.

11 July 1940: Promulgation of the French State by Marshal Pétain.

12 July 1940: Beginning of the Pétain-Laval cabinet.

18 July 1940: The New Hebrides rally to Free France

2 August 1940: General de Gaulle sentenced to death in absentia.

7 August 1940: Churchill-de Gaulle agreement laying the foundations of Free France.

8 August - 5 October 1940: The Battle of Britain.

26 August 1940: Chad rallies to Free France.

27 August 1940: Cameroon rallies to Free France.

29 August 1940: Middle Congo rallies to Free France.

30 August 1940: Ubangi-Shari rallies to Free France.

31 August 1940: Tahiti rallies to Free France.

2 September 1940: The French Establishments in Oceania rally to Free France.

7 September 1940: Weygand made the Vichy government’s delegate-general for French Africa.

9 September 1940: The French Establishments in India rally to Free France.

19 September 1940: New Caledonia rallies to Free France.

23-25 September 1940: Failure of the Anglo-Gaullist attempt off Dakar to rally French West Africa to Free France (Operation Menace).

27 September 1940: Tripartite Pact signed between Germany, Italy and Japan.

27 October 1940: General de Gaulle establishes the “Empire Defence Council”.

27 October - 12 November 1940: Gabon occupied by the Free French Forces.

12 November 1940: General de Gaulle appoints Félix Éboué governor-general of French Equatorial Africa.

22 November 1940: Leclerc made commander of Chad troops.

24 December 1940: “Empire Defence Council” recognised by Great Britain.

Operation Menace:

General de Gaulle wanted to broaden Free France’s political and territorial base by rallying French West Africa and Dakar, an important port that would prove a major asset to the British in the Battle of the Atlantic. The Allies therefore decided to mount the joint operation “Menace”.

Commanded by Admiral Sir John Cunningham, “Force M” set sail from Liverpool on 31 August 1940, arriving in Dakar on 23 September 1940. It consisted, on the British side, of nearly 4 500 men, two battleships, the Resolution and the Barham, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, four cruisers and ten destroyers; and on the Free French side, 2 400 men embarked on two Dutch liners, the Westernland and the Pennland, and three sloops, the Savorgnan de Brazza, the Commandant Dominé and the Commandant Duboc.

Meanwhile, to assert its authority over Gabon and attempt to take back French Equatorial Africa, the Vichy government dispatched from Toulon, on 9 September, three light cruisers of “Force Y”, in the command of Rear Admiral Bourragué. Taking advantage of Britain’s hesitancy, Bourragué managed to cross the Strait of Gibraltar, but shortly before Libreville he met two British cruisers and decided to go on to Dakar, reinforcing the defence of the port.

Repatriation of a wounded soldier aboard the Westernland. Source: Imperial War Museum.

Before making a show of force, General de Gaulle sent three delegations, including the one led by Commander Thierry d’Argenlieu, to persuade the city to join the Free French side without bloodshed. These overtures failed: the envoys were driven back by gunfire, d’Argenlieu being wounded in the process. Fighting got under way immediately. On the afternoon of the 23rd, the Free French tried in vain to land on Rufisque beach. The following day, the British in turn tried to take Dakar, and were no more successful. On the 25th, after a final attempt during which the destroyer Resolution was seriously damaged, Admiral Cunningham ordered a withdrawal. The operation was a total failure.

Rallying Gabon:

Surrounded on all sides by French Equatorial Africa, Gabon could represent a danger to the Allies. It was therefore important to bring it on side before reinforcements reached General Têtu, sent there by Vichy, which already had a handful of companies of tirailleurs, Martin bombers and warships, including the sloop Bougainville and the submarine Poncelet, to maintain security in the territory.

H39 tanks in the forest of Douala, en route to Gabon, October 1940. Source: Mémorial Leclerc et de la Libération de Paris / Musée Jean Moulin (Paris City Council)

The operation commenced on 27 October 1940: two columns, Parant and Dio, marched towards Libreville and Port Gentil. Sent from Middle Congo and Cameroon, they were comprised of tirailleurs and equipped with H39 tanks brought from Norway and disembarked at Douala. Lambaréné fell on 5 November 1940, but the progress of the two columns through the virgin forest was slow and difficult. Keen to get it over and done with, Leclerc organised a landing: arriving from Casamance, the Legionnaires that had joined Free France in July 1940 landed in the mangrove on the outskirts of Libreville, on the night of 8 to 9 November 1940. Supported by a small number of Lysander aircraft, they took the airport, then the city. Meanwhile, offshore, the Savorgnan de Brazza, commanded by Thierry d’Argenlieu, neutralised the Bougainville. Over the following days, Port Gentil laid down its arms.

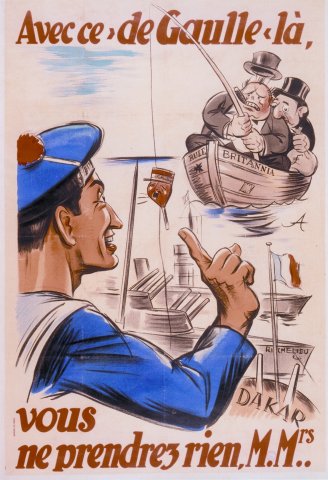

Retaliation by images:

The possession of overseas territories was as important to the French State as it was to Free France, and it was on the Empire that the conflict of legitimacy between Pétain and de Gaulle hinged.

With the Empire, the Vichy government intended to preserve national integrity as much as maintain some room for manoeuvre with Germany or a means of negotiating the relaxation of the demarcation line or improving the economic terms imposed on the French. Up until 1942, the Germans, meanwhile, used the Empire as a means of pressuring the French government, which was regularly prompted to intervene during the course of the war overseas. The reconquest of territories that had sided with Free France was therefore a matter of constant concern for Vichy. This attachment went on growing throughout the war, even as the French State gradually lost its grip on the Empire.

Poster produced by the anti-British Ligue Française poking fun at the Anglo-French failure off Dakar, 1940. Source: Musée de la Résistance Nationale, Champigny

Hence, at the same time as resisting Free France’s rallying attempts, it carried out a major propaganda campaign against the Allies. Newsreels endlessly exalted the overseas territories’ solidarity with metropolitan France, while satirical cartoons and posters undermined the image of the British prime minister and the leader of the Free French. To minimise their importance and take away all their credibility, they were ridiculed and their actions often made fun of. General de Gaulle was represented as Churchill’s puppet, while Churchill himself was portrayed as an instrument of the “capitalist Jewry”. Anti-British sentiment was intensified. “Perfidious Albion”, from whom no good could be expected (look at Mers el-Kébir), was France’s hereditary enemy and was using the allegedly “free” anti-French to oust its traditional rival. Allied and Free French setbacks were therefore systematically exploited and de Gaulle’s image diminished in order to demonstrate how weak and isolated Free France was.