1915-1916 The two births of the Canard Enchaîné

Le Canard Enchaîné was born during the war, against the war or, more precisely, against a certain "war culture". Neither defeatist nor, strictly speaking, pacifist, it stood apart among the French press.

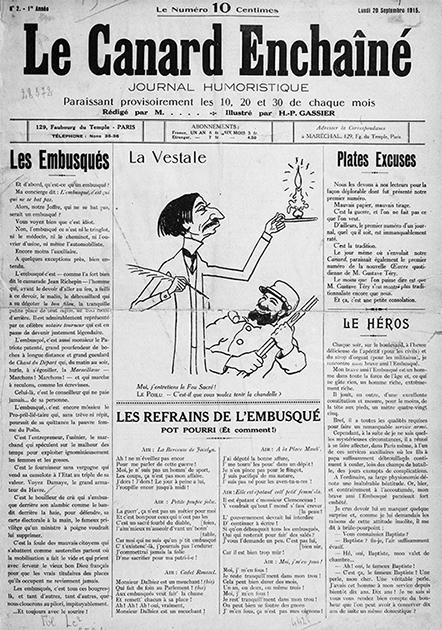

The "war culture" had had its finest hours in the first months of World War I, when Le Matin headlined that the Cossacks were just five stages from Berlin and L'Intransigeant claimed that "German bullets went in one side and out the other without causing any injury". Two journalists, who worked for newspapers practising this psychological rape of the masses saw this as "brain washing", a mixture of war-mongering chauvinism, misleading optimism, exaltation of the sacrifice of others and demonization of the enemy and so decided to react by founding a counter-propaganda newspaper.. through humour. On 10 September 1915, the editor Maurice Maréchal and artist Henri-Paul Deyvaux-Gassier, called H.-P. Gassier, published the first issue of Le Canard Enchaîné. Their first wish was to create a publication different from the others, independent of economic and political powers. In their view this meant systematic refusal of advertising, bank loans and outside investors: Le Canard would be clean because free, free because clean.

The name they gave to their newspaper is the result of a set of references and circumstances. The "canard" (duck) in French is a journalistic slang term meaning "news that is sometimes true, always exaggerated, often false" according to Gérard de Nerval and that commonly refers to a mistake, a voluntary hoax or an article written in advance. It was through self-derision and against the so-called "serious" press whose lies were sometimes worthy of the former "ducks" that Maréchal and Gassier took this name, as indicated in the presentation editorial on the front page of the first issue:

"Le Canard Enchaîné will take great liberty to only publish, after thorough checking, news that is strictly inaccurate. Everyone knows in fact that since the beginning of the war the French press has, without exception, only published relentlessly true news for its readers. Well the public have had enough! They wants false news... just for a change. They will get it."

From the beginning, it could be seen that Le Canard used a form of humour based on antiphrasis, litotes, feigned feelings. The purpose of the irony was to achieve greater efficiency: there is perhaps no stronger weapon than humour in French polemic debate and Maréchal, an assiduous reader of Voltaire, knew it well. To this was added the watchful eye of the censor, who prohibited excessively unorthodox opinions on the war. While La Vague by the pacifist Socialist Pierre Brizon was riddled with 'blanks' by the censors, and Clemenceau's L'Homme Libre was suspended for an excessively critical article about the poor hygiene on sanitary trains - he renamed it L'Homme Enchaîné (the chained man) in October 1914, which probably inspired the founders of Le Canard -, the small satirical newspaper, while often under pressure, escaped more than once from the vigilance of "Anastasie" - such was the nickname given to the censor - through its form of double-speak. In fact, as a reader claimed a few years later, there was more to read in one blank in Le Canard than in a year of Le Matin.

The first series in 1915 comprised five issues. Then it stopped. Its founders no doubt experienced difficulties in finding an audience. the artisan nature of the paper, a lack of organization and financial fragility did the rest and forced the two accomplices to interrupt the experiment. But they did not give up and on July 5, 1916, Le Canard reappeared and has continued ever since apart from the four years of the Occupation. The founders were still there but had gathered new writers around them, some of whom were to become famous in the years following the war: Henri Béraud, Paul Vaillant-Couturier, Roland Dorgelès made their debut at Le Canard, among other less famous journalists, Victor Snell, Georges de la Fouchardière, André Dahl, René Buzelin, Rodolphe Bringer on the writing side and Lucien Laforge, Jules Dépaquit, Bécan, Paul Bour and André Foy on the drawing side. Some, such as Gassier, left at the beginning of the 1920s; those who remained formed the backbone of Le Canard in the period between the wars. In addition to the stability of the teams, it is striking to see the longevity of some topics in the paper some of which are still present to this day either under their original title, as in "La Mare aux canards" on page 2, or in their original form "Les Livres". Over the years, the stability of the editorial framework became one of the hallmarks of Le Canard Enchaîné.

Le Canard was read everywhere in France right from the start. 40% of readers lived in Paris and surrounding region. the capital alone accounted for a quarter of the readers reported to the paper. The Parisian nature of the paper is well anchored. Soldiers, on the front, accounted for 20% of the total. Three regions in the provinces provided the bulk of the remaining readers: the Pays de la Loire; the Lyon region; Normandy. The delivery of paper to subscribers fighting on the front encountered serious difficulties. A reader who discovered Le Canard Enchaîné during World War I remembered that Le Canard was banned in the army zone" and that he thus received his paper in a "sealed envelope". Another reader - who claimed in 1962 to be the "oldest reader of Le Canard - remembered that his parents sent him issues that were "heavily censored and always hidden inside the local Rouen newspaper because at that time you weren't the kind of duck that was appreciated by army staff officers where I worked as a radio operator".

While there is no doubt that distribution of the paper on the front was closely monitored by the military authorities, it seems however that the outright ban on Le Canard Enchaîné had more to do with an initiative by some officers rather than a general across-the-board order. This is confirmed in a letter from another reader sent to the newspaper in October 1918:

"Some hidden sniper, with a sure hand / to save a few pennies / Keeps you on behalf of the Censors / By stealing from our soldiers on the Front".

The Le Canard Enchaîné was read by the soldiers for two reasons: escape from the "brain washing" and not be fooled by the leading newspapers; and keep informed about the gay Parisian life that echoed in the columns of the satirical weekly.

Read more

Bibliography

Le Canard enchaîné ou les fortunes de la vertu, histoire d'un journal satirique 1915-2005, Laurent Martin, rééd. Nouveau Monde, 2005.

Online article

The history of the War News programme from the army's cinematographic service

Video

Articles of the review

-

The file

Radio Londres, a weapon of war

"The great secret weapon wasn't the V1 or V2 bombs, it was the radio. And it was the English who developed it". So said Jean Galtier-Boissière at the end of the Second World War, a witness to the violent war of the airwaves that played out daily between three major radio stations, Radio Paris, Radio...Read more -

The figure

Philippe Viannay, founder of CFJ

A resistance fighter with the Défense de la France movement, visionary journalist Philippe Viannay was driven by this same spirit to found CFJ, the Centre for Journalism Studies, in 1946 with Jacques Richet, convinced that news is a profession that has its own rules and requirements.

Read more -

The interview

Christian Carion

After Merry Christmas, a historical fresco that looked at how soldiers on the front fraternised during the Christmas of 1914, Christian Carion has taken an interest in the exodus in his latest feature film En mai fais ce qu'il te plaît (Come What May). He talks about the reasons for his choice and t...Read more