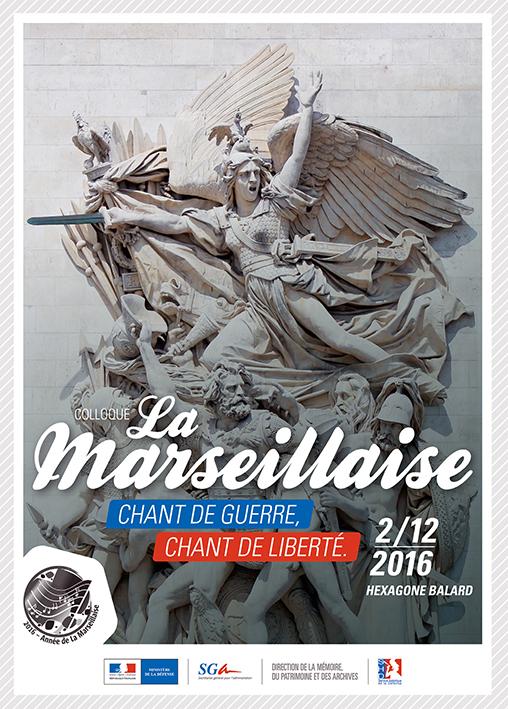

“La Marseillaise: a song of war, a song of freedom”

The anniversary year of La Marseillaise is brought to a close on 2 December 2016 with a conference at the Ministry of Defence. This scientific event, bringing together researchers from France and overseas, is an opportunity to look, from a historical as well as a musicological perspective, at the French national anthem's long history of significations and appropriations, its dissemination across the world, and its international destiny.

Composed in April 1792, after war was declared on Austria, La Marseillaise began life as a rallying song. It called to combat the battalions of volunteers who had joined up since 1791. In these times of revolution, war no longer depended only on the king's will. It involved the whole nation in what was a major political event. This meant a new role for military songs, whose purpose was no longer merely to glorify the fury of battle, but also to forge a body politic in its volunteering zeal.

Originally conceived as a “Battle song for the Army of the Rhine”, La Marseillaise was also a call to rise up against tyranny. Adopted by volunteers from Marseille who had come to join the troops on the borders, it accompanied the fall of the monarchy in August 1792.

Even before the proclamation of the Republic, the song of the volunteers asserted the sovereignty of the people and the defence of the Revolution by citizens-at-arms, who appropriated the res publica. Through action, war enabled the republican ideal to be achieved, even before it was accomplished institutionally. The fact is that the day after the Battle of Valmy, on 21 September 1792, the Republic was proclaimed. In 1795, the Convention instituted that link by adopting the battle song which was La Marseillaise as a “national anthem”. Born under the monarchy and written by an officer who was not fully in favour of republican ideas, the song had become a symbol of the Republic.

This first chapter in the story of La Marseillaise expresses its essential characteristic: the ability to say and suggest much more than a simple call to arms. So began the long history of its appropriations, which this conference will aim to retrace in three main sections.

THE INTERNATIONAL SUCCESS OF A NATIONAL ANTHEM

Abandoned by the First Empire, then by the successive regimes of the 19th century, La Marseillaise became France's national anthem once more on 14 February 1879, at a time when the Republic was consolidating itself and affirming its filiation to the French Revolution, from which it also derived its symbolic heritage: after the adoption of La Marseillaise, France's national day - the Fête Nationale, or Bastille Day - was set as 14 July, by the law of 6 July 1880. This official expression of the symbols of the Republic did not put an end to the appropriations, hijackings and controversies; far from it! The story of La Marseillaise as an endlessly reinvented, living heritage continued.

Closely bound up with the history of the Republic, it became an anthem of patriotic exultation, at a time of growing nationalist feeling, in the late 19th and early 20th century, then during the First World War. Some set it against the Internationale, while others, like Jaurès, declared their loyalty to both anthems, recalling that in the beginning the socialist anthem had been sung to the tune of La Marseillaise, highlighting the extent of its ambiguity.

Meanwhile, the anthem was prodigiously successful overseas, becoming the symbol of a number of revolutionary movements, and even the anthem of the Russian Revolution in 1917. The call to rise up against tyranny could indeed lend itself to all demands for social or political emancipation.

BETWEEN OFFICIAL HISTORY AND HIJACKING

International and deeply rooted in national history, the Marseillaise evokes both universal values and the specific history and identity of France. A symbol of the Republic, it has also become an emblem of France, brought up often in familiar terms. This explains the ease and frequency with which the anthem has been used in international popular music. A few notes are all it takes to conjure up an image of France, as shown, for instance, by the famous Beatles song, All you need is love.

Thus the solemn anthem intended for official celebrations becomes a familiar tune, which is played and sung on countless occasions and, at times, hijacked.

The irreverent and sometimes provocative ways in which it has been appropriated demonstrate, in their own way, the vitality of the anthem when it is sung, without ceremony, in stadiums. By an apparent paradox, the Marseillaise has become imbued with a familiar sacredness. The story of the sometimes critical, sometimes transgressive way in which the song has been appropriated, ultimately shows a form of attachment to this heritage and to the desire to make it one's own, even if it means transforming it. The recurring debate about changing any words regarded as too aggressive is one illustration. The rhetoric of “impure blood”, for instance, has attracted some criticism and rejection aimed, paradoxically, at transforming the Marseillaise to make it truer to itself and its idealised status as a song of freedom.

A COMMON HERITAGE

The key to this malleability lies without doubt in the very content of this highly ambiguous song. A battle song calling people to combat, it cannot be reduced to a brutal assertion of the aggressive impulse. The call for death to the tyrants also invites the French people to behave like “magnanimous warriors” in the fifth couplet. But beyond its ambiguities, the Marseillaise appeals to the emotions, thereby relativising the instability of its meaning. It is, first and foremost, a declaration of “sacred love” for the motherland and “cherished freedom”. Emphasised by an irregular rhythm, the musical form was clearly the ideal medium for this outburst of passion. The music, too, was the subject of a number of interpretations, which nevertheless led to the crystallisation of a common base particularly suggestive and well suited to the content of the lyrics.

The Marseillaise is thus a tremendous subject of study, which offers historians and musicologists an example of a living work, ceaselessly reinterpreted. Its vitality also shows the vigour of the principles in which the nation recognises itself.

Read more

Remembrance site

Articles of the review

-

The file

La Marseillaise, past and present

Inherited from the French Revolution, La Marseillaise has been a part of French history for more than two centuries, both in times of hope and jubilation, and at its most tragic times of hardship and upheaval. A symbol of unity, it became the rallying cry of the champions of freedom, in France and a...Read more -

The figure

Rouget de Lisle and La Marseillaise

Designed and produced by the Musée de l'Armée as part of “2016, the year of La Marseillaise”, this documentary exhibition, shown in the main courtyard of the Hôtel des Invalides until October, has since become a touring exhibition, also accessible via the museum's website....Read more -

The interview

Aurore Tillac

The official choir of the French Republic, the choir of the Republican Guard is formed of 45 French singers, recruited from among the elite of the discipline. Director of the choir since 2007, Aurore Tillac talks of the special place of La Marseillaise in the official repertoire....Read more