1963 to 2011: 50 years of OPEX

From 1963 to the present, dozens of overseas operations have been carried out, involving military personnel from across all the armed forces, directorates and services: army, navy, air force, joint armed forces directorates and services, and Gendarmerie Nationale. By telling the story of certain military operations of recent decades and the reasons that led to France’s involvement in these foreign theatres, a genuine history of French overseas operations, or ‘OPEX’, can be written.

Overseas operations: a concept that is hard to pin down...

If, as Napoleon Bonaparte put it, “the strategy of a State is in its geography”, then it is France’s vocation, as a land power with an extensive coastline, to involve itself both in Europe and in the rest of the world. Either out of necessity or because it gave credibility to its vocation as a major power, overseas action has been a constant in French military history. Yet it has often been limited by the existential need to defend first and foremost its own borders. Put another way, France sought security on the European continent - historically through the balance of power, domination or cooperation - in order to gain freedom of action and exert an influence around the world. Recalling this strategic constant helps underline the originality of the current situation, in which, for the first time ever, external action has become the priority in the country’s defence policy.

Coming to the fore about two decades ago, the popularity of the term “overseas operation” (opération extérieure, or OPEX, in French) reflected this new orientation in the operational activity of the French armed forces. As engagements got tougher, it gradually became a synonym for “armed conflict”, offering a comfortable substitute for the word “war” itself. From then on, troops were sent on an “overseas operation” in the same way as previously they went “to war” or “to the front”. Yet overseas operations refer to a reality that is both multi-faceted and dates back further, linked to a defence policy drawn up at the time of the African wars of independence, over half a century ago, and continually updated ever since.

So, what is meant by “overseas operations”? There is a clear geographical criterion, but it is not enough to define them, since not every military presence overseas is necessarily in an operational context. In fact, the term covers a highly diverse reality, which explains the vagueness surrounding the concept. As Louis Gautier puts it: “Overseas operations developed in a relatively spontaneous and profuse fashion. The concept of overseas operations is a catch-all concept. From humanitarian action to the fight against terrorism, overseas operations are militarily diverse. They appear poorly categorised in terms of policy and order of priority.” The definition of a overseas operation therefore remains very broad, even in official documents, such as General Bernard Thorette’s report concerning the construction of the Memorial to French soldiers killed in overseas operations: “An overseas operation means any use of the armed forces outside national territory (whether they are deployed to the theatre or operate from French soil), in a context characterised by the existence of threats or risks liable to cause harm to the physical integrity of the troops.”

... but a clearly identifiable historical subject

As we can see, these definitions encompass a very broad spectrum and offer barely any indication of the specific nature of contemporary operations as compared to the many forms of overseas intervention carried out previously, from the expeditionary corps to gunboat diplomacy. More than a particular mode of action, it is the context and initial intention that define the place of overseas operations in the history of the armed forces. This “era of overseas operations”, from 1963 to the present, is characterised by the systematic use of military action to resolve crises of variable intensity, a commitment that accompanied the renewal of France’s African policy following the liquidation of its colonial past (independence of the countries of sub-Saharan African in 1960, the Bizerte Crisis in 1961, end of the Algerian War in 1962). From 1963 onwards, France’s overseas military action was characterised by a desire to be a stabilising or mediating influence, detached from any spirit of conquest, whether in the defence of French interests or to honour international commitments. It took the form of a deployment of units, pre-positioned or deployed from metropolitan France, for a specific, one-off mandate that could be extended. Initially very limited, to begin with these operations concerned only specialised troops, often heirs to a strong colonial tradition (marines, Foreign Legion, paratroopers), and who represented the professional elements of the conscription army. But once the threat had disappeared from Europe at the turn of the 1990s, the armed forces were professionalised and their format was reduced. Gradually, all conventional components became deployable.

Thus, charting the history of overseas operations means following, alongside the story of the military operations themselves, a process of adaptation by which evolving international crises profoundly transformed the French armed forces.

The French concept of overseas intervention at the origin of OPEX (1963-1978)

In the early 1960s, the end of decolonisation meant that France could now focus its military efforts on safeguarding national territory and modernising its armed forces, with priority given to the constitution of a nuclear deterrent. Accordingly, on 16 September 1960 the decision was taken to drastically reduce France’s overseas military presence, cutting the garrisons in Africa by ten over a decade to reach 6 000 by 1970. However, that disengagement marked a reorientation rather than a genuine break in policy, since the French withdrawal was not on such a massive scale as planned. The newly independent African States continued to want France to contribute to their security, while France made its presence in Africa a constant in its strategic engagement for a variety of reasons (economic interests, surveillance of maritime routes, defence of the French-speaking community). At the confluence of these reciprocal interests, the new concept of overseas intervention in the postcolonial era was described as follows by Charles de Gaulle in his speech in Strasbourg on 23 November 1961: “In new forms adapted to our century, France is, as it has always been, present and active overseas. As a result, its security, the help it owes its allies, the assistance it is committed to provide to its partners, can come under threat in any region of the globe. A land, air and naval intervention force, designed to act anywhere, at any time, is therefore of paramount importance. We are beginning to realise this.”

Overseas military action under the Fifth Republic was thus restructured into three aspects, which continue to characterise it today: the pre-positioning of small forces overseas, the provision of technical military assistance to train foreign armies and the maintenance of a crisis response capability. The latter is the basis of the French concept of overseas intervention. Initially, only “blitz” operations under a defence agreement were envisaged. From 1964 onwards, then, each of the armed forces had to maintain a core force on permanent standby, ready to be deployed without notice: these were Guépard (a parachute regiment), Tarpon (an amphibious naval group) and Rapace (a unit of combat and transport aircraft). Large-scale mixed-force manoeuvres were organised to justify this concept of use. They highlighted the rapidity of intervention by air as compared to by sea, while it was now less a matter of mobilising a full expeditionary force than of developing the means to deploy light actions almost immediately.

Operation Lamantin, Mauritania, 1978. © FX. Roch/ECPAD

The first operations to be carried out according to this concept of use were Lamantin (Mauritania, 1977 and 1978) and Bonite (Zaire, 1978). The original aspect of Operation Lamantin was that it was carried out solely by air force elements based in Dakar. At that time, the Polisario Front was calling for the independence of the Western Sahara and threatening to bring about the collapse of Mauritania by attacking the railway line used to transport iron ore, the country’s only resource. France deployed a highly streamlined yet powerful force against them: ten Jaguar fighter-bombers supported by supply, transport and maritime patrol aircraft. On five occasions, the Jaguars intercepted enemy motorised columns, causing them sufficient losses to make them cease their activity and bring the Polisario Front to the negotiating table.

Meanwhile, Operation Bonite was a spectacular evacuation of French nationals conducted by force in the heart of Zaire. In May 1978, Katangese rebels occupied the mining town of Kolwezi, in the south of the country, and took its European population hostage. When it heard the news, France decided to intervene. On 17 May, the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment was given the mission to recapture the town to evacuate the population. Transported to Kinshasa on the 18th, they were dropped on Kolwezi in two waves, on 19 and 20 May, recapturing it after violent fighting that cost the lives of five and wounded 15 among their number. A major success, Bonite demonstrated the rapidity of response and the flexibility of the French units deployed in two days nearly 8 000 km from their base. Still today, this type of rapid action using light forces that are nonetheless capable of turning around a dangerous local situation remains the archetype of “French-style” overseas intervention, as Operation Serval (Mali, 2013) once more clearly demonstrated.

Operation Limousin, Tchad, 1970. © RP. Bonnet/ECPAD

However, the 1970s also saw larger-scale deployments which underlined the limits of the initial concept. For instance, long, repeated operations, such as Limousin (1969-71) and Tacaud (1978-80), had to be carried out in Chad, to defend the country against chronic rebellions. The mixed-force nature of Operation Tacaud also marked a turning-point, with the French navy contributing to the surveillance of the Saharan areas with its Breguet maritime patrol aircraft.

At the same time, a twofold boost was given to the overseas intervention capacity of the French armed forces. First, they received reinforcements from the conventional forces, initially committed under the third Law of Military Planning (1971-75) and pursued with General Lagarde’s reform, in 1975. The aim was to limit the distinction between the “forces of manoeuvre”, responsible for defending French borders against the Warsaw Pact countries (the First Army), the “territorial defence forces”, responsible for protecting strategic facilities (reserve units, academies, gendarmerie), and the “intervention forces”. In practice, however, the deployment of troops on overseas operations remained politically highly sensitive, and only the 9th Marine Infantry Division and the 11th Parachute Division, comprised mainly of professional soldiers, were deployed to foreign theatres. It would not be until the end of military service, announced in 1997 and which took effect in 2001, that the desired degree of versatility was attained.

Second, French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing wanted to adopt an all-out defence policy, or, at least, one not geared only to the East: “I think that in today’s world the dangers could come from many parts of the world, so our armed forces need to be mobile forces.” Accordingly, the main resources of the French navy, which up until then had been concentrated on the Atlantic coast, were reoriented to the Mediterranean, Red Sea and Indian Ocean. French minesweepers participated in clearing the Suez Canal of mines, between 1974 and 1978, and the independence of Djibouti was guaranteed by sending the naval air-force group on two occasions (Operation Saphir 1, in 1975, and Saphir 2, in 1977); Djibouti went on to become one of the main French bases in Africa alongside Dakar.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the French armed forces monitored the maritime routes off the coast of Africa (the Gulf of Guinea, Red Sea and Mozambique Channel), and occasionally intervened in the interior of the continent, on NATO’s southern flank, in the face of a growing Soviet influence in the Central African Republic, Ethiopia and Libya. But Paris did not hesitate to extend its influence beyond its own backyard, to countries other than its former colonies (Zaire, Burundi, Rwanda, Equatorial Guinea).

Convoy on the Saïda road, Lebanon, 1978. © FX. Roch/ECPAD

One first departure from the operations carried out up till then came with the involvement of a French contingent in the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), in 1978, in a context that prefigured those of the decades to come in more ways than one: a civil war between multiple factions, an operation with a UN mandate imposing very strict rules of engagement, and a multinational force that saw units working side by side yet without forming a genuine coalition. The French troops, accustomed to the African interventions, found themselves out of step here and, as early as 1979, most of the French contingent re-embarked.

The limitations of the French model of overseas intervention in the face of a growing diversity of crises (1978-1991)

One might have thought that the accession to power of François Mitterrand - “the president who didn’t like war”, to quote the title of Alexandra Schwartzbrod’s book - would shift the emphasis away from overseas interventions. But, on the contrary, President Mitterrand was not afraid to use armed force to defend France’s international standing, as a permanent member of the Security Council, or to support the idea of Europe as a power in control of its own destiny. However, this Mitterandian use of armed force remained within clearly defined limits: the actions were carried out in accordance with international law; their aim was to restore the rule of law and security; lastly, they made limited use of violence and only used the means strictly necessary to accomplish their mission.

During François Mitterrand’s first seven-year term of office (1981-88), France engaged in a new peacekeeping effort in Lebanon, as part of the Multinational Force. Between 1982 and 1984, 2 000 French soldiers were stationed in Beirut, supported from the sea by a permanent naval force, via the Olifant missions. This engagement led to a direct confrontation with Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shiite Islamist party backed by Syria and Iran, which was behind the suicide bombing of the French Drakkar barracks. In comparison, the reprisal raid by French naval air force Super-Étendard fighters was more symbolic than effective. Finally, on 31 March 1984 the French contingent left Beirut for a second time. By that time, the French population had discovered the risks inherent to peacekeeping missions and, incidentally, the role of its armed forces in foreign theatres.

Operation Manta, Tchad, 1983. © B. Dufeutrelle/ECPAD

The interventions in Africa similarly continued to be carried out in accordance with defence agreements. France collided in particular with the ambitions of Colonel Gaddafi, who sought to extend Libyan influence to Chad by backing Goukouni Oueddei’s insurrection against the government of Hissène Habré. On two occasions, Paris deployed significant numbers of troops to counter the insurgency. In Operation Manta (9 August 1983 - 11 November 1984), 3 500 troops were sent to Chad, with support from the Bangui and Libreville air bases. The goal was to defend the capital N’Djamena and support the Chadian National Armed Forces (FANT) in regaining control of the north of the country. In January 1984, the French air force bombed the rebel columns, losing one Jaguar and its pilot; but the insurgents were contained beyond the “red line” of the 16th parallel. In October and November 1984, the French forces were withdrawn under a Franco-Libyan withdrawal agreement, in Operation Silure.

Meanwhile, the aircraft carrier Foch was discreetly deployed off the Libyan coast, ready to launch reprisals in case Tripoli violated the agreement (Operation Mirmillon). But the launch of a new Libyan offensive south of the 16th parallel forced Paris to engage once more, on 16 February 1986. Operation Épervier made heavy use of air power and anti-aircraft weapons, because its aim was essentially to eliminate Libyan air support to the Chadian rebels. The French air force carried out a successful raid against the Ouadi Doum air base, while the destruction of a Libyan Tupolev bomber by a battery of Hawk anti-air missiles proved dissuasive. Free from any threat from the air, the FANT won on the ground the so-called “Toyota War”, by modernising the traditional Saharan practice of the razzia (rapid raids on enemy territory) using pickup trucks equipped with Milan anti-tank missiles. Although a ceasefire was agreed in September, the Épervier force was reduced but not completely withdrawn, due to the particular importance which the defence of Chad represented for France’s African policy. An important stopover for flights to equatorial Africa and the Indian Ocean, N’Djamena formed with Dakar, Bangui and Libreville a network of air bases that provided mutual support to one another. The continuity and scale of the resources employed in Chad heralded a shift in French defence policy towards overseas operations in the following decade.

Operation Epervier, Tchad, 1986. © P. George/ECPAD

Finally, in 1987-88, the French navy conducted its most spectacular mission of naval diplomacy, Operation Prométhée. Against a backdrop of crisis that culminated in the breaking off of diplomatic relations between Paris and Tehran, the aircraft carrier Clemenceau was deployed to the Arabian Sea to deter Iran from acting against French interests and to protect maritime routes in the Persian Gulf. As a sign of the importance he attributed to this show of force, President Mitterrand gave a long television interview from the bridge of the aircraft carrier during the mission; it remains to this day a unique example in the history of French overseas operations of the use of military symbolism by the executive.

Thus the period 1978-1990 can be regarded as the culmination of the traditional model of overseas intervention under the Fifth Republic. With the exception of Lebanon, the operations were carried out with a national mandate, often as part of a bilateral agreement. In this period, particular emphasis was placed on intervention forces, which became the spearhead of the armed forces and were grouped together, in the case of the army, in the Rapid Action Force (FAR), established on 1 July 1984. Tasked with intervening both in overseas theatres and in Central Europe, the FAR prefigured, to some extent, the professional army created to form expeditionary forces.

However, the model, based on the moderate use of military capacity against a limited opposition, was called into question by the scale of the Gulf War, in 1990-91. Here, a significant capability was deployed against a modern fighting force whose capacity was overestimated at the time. Conscription emerged as a major handicap to the formation of the French contingent, and the shortcomings in capacity meant it had to fight with allied support or, in the case of the navy, not to take part in all the engagements.

The French armed forces and the challenge of adapting to post-Cold War international crises (1991-1999)

With the unexpected outbreak of the Gulf War came the revival of high-intensity conflict in an inter-allied, mixed-force context, something not seen since the Suez Crisis. The French experience in the conflict (2 August 1990 to 28 February 1991) began with naval diplomacy operations, with the deployment of the aircraft carrier Clemenceau and the imposition of an embargo on shipping. Next came an air campaign, and finally the intervention of a light armoured division on the Iraqi sands. It marked a decisive turning-point for French overseas operations, from three points of view.

First, by determining a decision-making process in times of crisis which contrasted strongly with the absence of clear rules that had prevailed up until then. The French President publicly asserted his role as commander-in-chief of the armed forces, when he famously said “We are on a war footing.” Daily, he presided over a select committee of ministers, military leaders and senior civil servants, who were thus in direct contact to coordinate the actions marking each stage of French engagement. Close to the executive for which he was spokesman, the chief military adviser to the French President took on renewed importance, playing the role of intermediary which proved decisive.

The change in geopolitical context was a second shift. The Gulf War was situated on the dividing line between two strategic worlds: interstate conflict, arising out of the Cold War, and that of a new strategic order, centred on the power of the United States. The Daguet Division and its air support had been deployed in Iraq with an autonomy of command that might have created the illusion of national independence in the defensive phase of the conflict, Operation Desert Shield. But from October onwards, the planning of Operation Desert Storm required the French units to come under US command or else be left out of the final offensive. From that point on, French decision-makers agreed that they would no longer engage in a major conflict without the joint participation of the United States, and that meant preparing themselves accordingly.

Lastly, the move towards greater interoperability with our allies went hand in hand with the completion of a process of integration of the armed forces that was already under way. Integration with our allies necessitated integration between our own armed forces. The results of a consultation led to the creation of new mixed-force bodies, such as the Strategic Affairs Commission (DAS), Department for Military Intelligence (DRM), Special Operations Command (COS), Joint Operations Centre (COIA) and Joint Command for Operational Planning (EMIA-PO), the latter two subsequently merging to form the current Centre for Planning and Execution of Operations (CPCO).

With the white paper of 1994, the deployment of force ceased to be a marginal phenomenon to become the new strategic approach of the French armed forces. Indeed, the 1990s saw an increase in the number and diversity of the engagements deserving of the umbrella term “overseas operations”, even though often the only thing they had in common was that they took place overseas. The wide variety of mandates under which French forces operated also indicate that France sought an appropriate framework for implementing its international security policy.

To begin with, there were the operations in support of its African allies. At that time, Africa was plunged in economic, political and environmental crises necessitating isolated yet recurrent operations of humanitarian assistance or to evacuate French nationals. These prompted France to engage strongly in the training of the African armed forces, by devising the RECAMP (Military capacity-building in the African countries) programme. The French navy, too, participated in this military cooperation initiative with the African countries, through Mission Corymbe, which involved the permanent presence of a warship in the Gulf of Guinea.

Cambodia, 1992. © M. Riehl/ECPAD

At multinational level, initially priority was given to operations with a UN mandate: peacekeeping in Cambodia (UNTAC, 1992), humanitarian aid in Somalia (Operation Oryx, 1993) and in Rwanda, where Operation Turquoise (June-August 1994) brought French soldiers face to face with the terrible reality of the Rwandan genocide. But the most significant overseas operation of the decade was France’s involvement in peacekeeping in Yugoslavia, as part of UNPROFOR (1992-95). Militarily, the poorly defined mandate and imprecise terms for the use of force perturbed the service personnel, divided between empathy for the population caught up in the war and the absence of an operational decision to put an end to the situation. The recapture of Vrbanja Bridge, on 27 May 1995, resulting in the freeing of a number of French personnel who had been taken hostage, demonstrated that the troops had not lost their fighting spirit. But this symbolic turn of events could not mask the bitter failure of UNPROFOR.

The situation finally culminated in the recognition of a US leadership and the reform of NATO’s strategic concept, in March 1999. From a defensive alliance in Europe, NATO became a military crisis management organisation with a much wider remit. At the same time, the framework for humanitarian operations was redefined by the notion of the “right to intervene”, which, although challenged politically, sought to provide greater freedom of military action in the face of crises: “peacekeeping” was replaced by “peace enforcement”. The Kosovo War was a test bed for this new, tougher policy of intervention, which took the form of an aerial bombing campaign codenamed Operation Allied Force.

On 3 June, Belgrade finally agreed to withdraw its forces from Kosovo and allow the occupation of the province by NATO (KFOR) troops. With 101 air force and navy aircraft, France represented the second largest contingent in the coalition and participated in all missions, by day or by night. The conflict showed the extent to which the armed forces were able to adapt to the new operational model, anticipated since the Gulf War, characterised by high-intensity offensive operations carried out as a coalition. It is all the more remarkable since the new generation of weaponry (Rafale fighters, Scalp/Storm Shadow cruise missiles, nuclear aircraft carriers) had not yet entered service and France’s defence capability was in the process of transformation, with the post-Gulf War reforms and the expectations of professionalisation. Announced by President Jacques Chirac in October 1997, the end of conscription was to take effect in June 2001.

Overseas operations as the only operational approach for the armed forces (2000-2011)?

At the dawn of the new millennium, the lasting absence of a continental threat and the professionalisation of the troops led to an increase in overseas operations, now one of the three fundamental missions of the French armed forces, together with protection of the territory and population, and nuclear deterrence. Units became more versatile, as the former distinction between metropolitan and overseas troops no longer applied. During this period, the French army, taken as a whole, can be said to have become an expeditionary force of 30 000 troops, deployable for six months, according to the objectives of the White paper of 2008. In practice, the troop numbers deployed annually between 2000 and 2015 varied between 14 500 (in 2000) and 8 000 (in 2015), though often for much longer operations.

Continuing an already well-established trend, overseas operations succeeded or overlapped one another, as now well-known theatres of operation (Côte d’Ivoire, 2004; Chad, 2008) were joined by brand-new ones (Afghanistan, 2002-13), along with new security threats, such as combating piracy.

Operation Licorne, Côte d’Ivoire, 2011. © S. Dupont/ECPAD

In Côte d’Ivoire, Operation Licorne was a protracted operation (2002-15), in which French forces intervened between the two factions fighting over the country. It was marked by two particularly tough periods. In the first, in November 2004, after an attack by government aircraft killed nine soldiers of the Bouaké camp, Paris retaliated by destroying the Ivorian air force on the ground. In the second, in March-April 2011, the Licorne Force intervened in Abidjan to protect the 12 000 French nationals in the capital and ensure that the election result, recognised by the UN and the African Union, was respected.

But what left the most profound mark on the soldiers of this generation has to be the Afghan experience, especially following the increase in the French contingent and the allocation of a specific zone of responsibility, Kapisa Province (2008-12). The revival of counter-insurgency - with the civilian-military action among the population which characterises it - together with a certain trivialisation of combat actions, were the most prominent aspects of the Afghan legacy. The result was an undeniable hardening of the conflict, paid for in blood: with ten French soldiers and their Afghan interpreter dead, and 21 wounded, the losses suffered in the Uzbin Valley ambush, on 18 August 2008, were the heaviest in a single action since the Drakkar suicide bombing, 25 years earlier. This prompted major controversy about the terms of engagement and the operational standard of the French troops - though not, it should be noted, about the appropriateness of the operation itself.

Operation Atalante, 2009. © DR/ECPAD

Meanwhile, the marines confront a less overt, but equally persistent, security threat: the resurgence of piracy, in particular off the coast of the Horn of Africa. Since 2008, they have participated in the European Union operation to counter piracy in the Indian Ocean, EUNAVFOR Operation Atalanta, which consists of maintaining the security of maritime routes and escorting ships of the World Food Programme. On two occasions, French vessels distinguished themselves by freeing yachters taken hostage by Somali pirates (cases of the yachts Le Ponant and Le Carré d’As, in 2008).

Operation Harmattan, Libya, 2011. © JY. Desbourdes/ECPAD

The overseas operations that have taken place since then have confirmed the higher operational standard of the French armed forces, especially Operation Harmattan against Libya, in 2011. Following the uprisings that shook the Arab world in December 2010 (the “Arab Spring”), February 2011 saw a challenge to the power of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, in particular in the province of Cyrenaica, traditionally rebellious towards the central government of Tripoli. France’s initial actions concerned humanitarian aid and crisis management, but by March the situation had got out of control. On 19 March, on the basis of UN Resolution 1973, voted two days earlier, France engaged militarily in the Libyan civil war, with an air raid against the self-propelled guns threatening Benghazi. The seven-hour raid, launched directly from air base 113 in Saint Dizier, France, signalled the start of Operation Harmattan.

Unusually, it was carried out primarily by France and the UK, under NATO command but with only US backing, showing Washington’s desire to disengage from overseas interventions after a decade of fierce combat in Afghanistan and Iraq. But the fact remains that the massive salvo of American and British cruise missiles launched on the night of 19 to 20 March was decisive in neutralising Libyan air defences. Then came three unequal stages of operations: the initial stage of strikes to halt the advance of troops, until 31 March; then a long period of attrition culminating in the capture of Tripoli by the insurgents, on 27 August; finally, the reduction of the last pockets of loyalist resistance. The death of Colonel Gaddafi, on 20 October, signalled the end of the campaign and the fall of the regime, but marked the start of a new period of instability in Libya, which persists today. At each of these stages, the French armed forces distinguished themselves with their engagement in the action. First of all, through air strikes carried out from Corsica and from the aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle, positioned as close as possible, 60 to 120 miles from the shore. Next, through tactical daring, including the revival of naval gunfire support (3 000 artillery shots fired) and a remarkable demonstration of air combat capacity by army helicopters from the fleet’s helicopter carriers. In the end, French forces were responsible for 28% of coalition sorties, but 35% of offensive sorties. Admittedly, Libyan geography and the adversary’s fairly poor military capability favoured this demonstration of power projection, but the fact remains that, through Operation Harmattan, France seems to have wanted to demonstrate the advances in capacity made by each of the armed forces and their ability to successfully incorporate them in an overall plan.

What approach should be taken to 50 years of overseas operations?

For the armed forces, the history of overseas operations charts their operational record over the past five decades. During that period, the deployment of forces went from being a secondary role, for which certain units were specialised, to a core purpose, the real beating heart of the armed forces, around which the entire military capability was built, with the exception of the nuclear deterrent. Overseas operations thus led to the creation of new, large units, justified professionalisation and, finally, mobilised the entire structure of national defence, including the Secretariat-General for Administration (SGA), for legal, financial, human resources and remembrance issues.

As a result, the three armed forces are extremely well adapted to this mission and have enhanced force and power projection capabilities, leading to real tactical and operational successes (Libya in 2011, Mali in 2013). For instance, Operation Serval prompted not only flattering comments from across the Pond, but a debate around what lessons the US Army could learn from the “light”, “rustic” French model. Though that “model” often arises out of necessity alone, it is interesting to note how it has brought France recognition as one of the few powers capable of intervening autonomously to influence the course of a distant conflict.

Even so, the adaptation process has not been without its tensions. First, because it has been accompanied by a reduction in format that has exposed overseas operations to a heightened risk of “operational overload”. Second, from a financial point of view, because the cost of overseas operations has been systematically underestimated by the Initial Budget Act, despite the fact that it has risen rapidly (from an average of EUR 723 million between 2002 and 2005, to around EUR 1.1 billion between 2013 and 2015 and EUR 1.2 billion in 2016); this absence of budgetary realism, regularly denounced by the court of auditors, means the burden is shared between all ministries. Third, because the priority given to overseas operations in practice often translates as a strong focus on those operations currently under way, with a short-term view being favoured over forward-looking research or a medium or long-term strategy. The result is fluctuating interest, for instance in counter-insurgency warfare prompted by the deployment in Afghanistan.

Might we then go so far as to speak of “expeditionary excess”? The question would depend on our being able to make a judgment about the strategic impact achieved by this policy and find out the views of citizens on this issue. Yet the impact of overseas operations on the link between nation and armed forces is difficult to ascertain. While protection of the territory and population is the most obvious raison d’être of national defence, overseas operations are not a natural source of legitimacy for the armed forces. And the end of conscription similarly prompts fears of weakening ties between nation and armed forces. But we are nevertheless a long way from the suspicions of militaristic excess elicited by a vigorously active professional army under the Third Republic (1870-1940). Besides, Parliament has seen its role as supervisor of overseas operations strengthened by the constitutional reform of 23 July 2008 amending Article 35 of the French Constitution. That article requires the government to notify its decision to engage the armed forces no later than three days after the start of the operation, and to obtain parliamentary authorisation after four months.

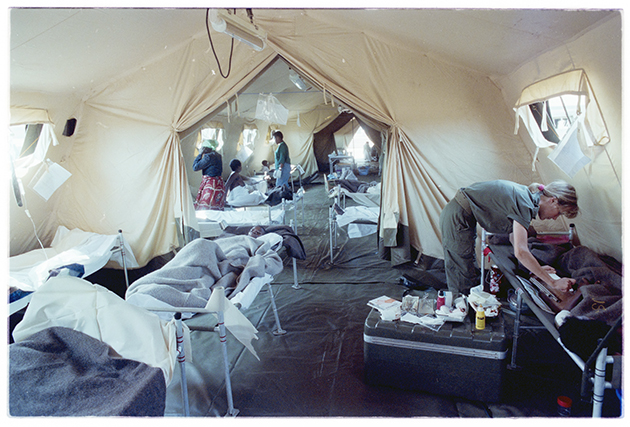

Healthcare provision in the children’s ward in Cyangugu, Rwanda, 1994. © X. Pellizarri & C. Savriacouty/ECPAD

Remarkably, the at times extremely harsh criticisms of French interventionism appear to focus on the political fundamentals purported to be behind the decision for intervention (against French “neocolonialism” in Africa, or “Atlanticism” in the case of interventions with a NATO mandate, for example), rather than on the military aspects of the operation itself. One notable exception was Operation Turquoise, in Rwanda, which prompted accusations as serious as they were contentious, about the reasons for French intervention as well as the action of the troops on the ground.

While a UN mandate generally meant that an operation was viewed in a positive light, ultimately it did not spare those forces involved in failed UN peacekeeping operations (Yugoslavia, 1992-95; Somalia, 1993). Yet only the Gulf War, in 1990-91, gave rise to peaceful demonstrations, doubtless because it was announced to the public as a conflict whose foreseeable intensity brought back memories of the last world war. This initial analysis would need to be backed up by a look at the reactions to the “hard blows” that were the Drakkar suicide bombing, the French peacekeepers taken hostage in the former Yugoslavia, or the Uzbin Valley ambush. The latter prompted great controversy, even raising questions about the military commanders’ legal responsibility, but the reason the French troops were in Afghanistan in the first place was never really challenged.

The likely conclusion to be drawn, therefore, is that there is a kind of acceptance of the phenomenon of overseas operations as a normal, standard framework for intervention by our armed forces. From 2007, when the enhanced intervention in Afghanistan began, two observations back up this analysis. The first is the renewed interest in eye-witness accounts, with the publication of a number of books, written either by journalists or, what is far more revealing, by members of the armed forces of all ranks. The books were well publicised by the press, and subsequent operations (Libya, Mali) confirmed the trend.

The second is a greater interest from the civilian world in service personnel killed or wounded on deployment. As well as the official memorial services at Les Invalides, tributes began to be held by charities on the Pont de l’Alma. Disabled war veterans and those suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder received more attention both from the public and from the authorities.

Finally, the word “war”, long camouflaged by military jargon (beginning with the term “Opex” - “overseas operations” - itself) regained some of its former prestige. The choice, in 2011, to rename the former Joint Defence College the École de Guerre, or ‘School of War’, is indicative of this trend, and politicians seized upon it once more after the terrorist attacks in Paris, in 2015. It must clearly be seen as a sign of the growing realisation that the conciliatory climate which marked the end of the Cold War is now behind us.

Dominique Guillemin - History and Geography Teacher, currently studying for a PhD in history, Service Historique de la Défense

Operation Lamantin, Mauritania, 1978. © FX. Roch/ECPAD

Des soldats du 1er régiment de hussards parachutistes patrouillent aux abords de leur PC, Liban, 1984. © P. Fernandez/ECPAD

The aircraft carrier Clemenceau. Operation Salamandre, Djibouti, 1990. © M. Riehl/ECPAD

Mission Oryx, Somalia, 1992. © D. Viola/ECPAD

Operation Trident, Kosovo, 1999. © X. Pellizarri/ECPAD

Le colonel Duffour interviewé par RFI, Afghanistan, 2005. © A. Battestini/ECPAD