The Battle of Saumur

Sous-titre

19-20 June 1940

On 10 May 1940, when the “Phoney War” was over, Germany sent its armies against France and Belgium.

After prevailing in the Somme and the Aisne, the enemy advanced on the Seine. General Weygand, commander-in-chief of the French armies since 20 May 1940, ordered the defence of all rivers that might block the path of the invasion to the south.

Thus, at the end of May, it was determined that the Loire should be defended, under the command of General Vary.

The section of the river that stretches from Port Boulet (Indre-et-Loire) to Gennes (Maine-et-Loire) was to be the scene of a now legendary battle to delay the invaders.

The Saumur Cavalry School was allocated the sector between the confluence of the Vienne and the Loire, in the east, and Le Thoureil in the west, i.e. a front spanning some 40 km. In this sector, there were already a number of units, many of them survivors of the earlier fighting: elements of the 19th Dragoons Regiment and the 13th Regiment of Algerian Tirailleurs (13th RTA), the remains of the Groupe Franc of Neuchèze, etc.

Maxime Weygand. Source SHD

This front comprised four crossing points of the Loire: the Monsoreau bridge, the railway bridge, the Saumur bridges on either side of Offard Island, and the Gennes bridge.

The German troops first crossed the Seine on 10 June. On the 14th, they entered Paris. The Loire was the only remaining obstacle from which to make a last stand.

On 15 June, the Cavalry School – which was not a combat unit – received orders to retreat to Montauban.

For its commander, Colonel Michon, this order created a dilemma: following it would make a 40 km hole in the Loire defences. Initially, he obtained consent to send back only those elements unfit for combat, keeping in place the officers and cadets.

On 17 June, the order to stop the fighting was given by Marshal Pétain, who had requested an armistice. Colonel Michon consulted his officers: for the honour of the school, all chose to fight the Germans on the Loire.

Against two German divisions – nearly 40 000 men and 300 pieces of artillery – that were advancing towards the Saumur area, the French had 2 500 men: 550 cavalry officer cadets, 240 transport officer cadets, 300 infantrymen and machine-gunners of the 13th RTA, etc. They were poorly armed: five 75 mm field guns, 13 anti-tank guns, and a handful of 60 mm and 81 mm mortars. The cadets of the Cavalry School were armed only with one rifle per man, together with St Étienne 1915 machine guns for training purposes.

In view of these limited resources, the bridges would constitute the points of defence.

On 18 June, at 1.30 pm, as the Germans approached, the French elements, command and squadrons, took up their planned positions.

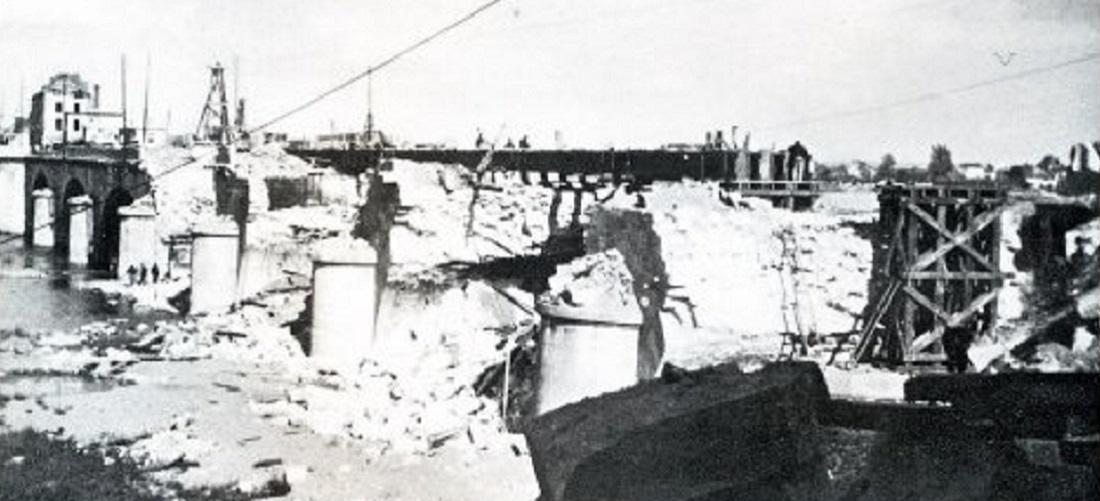

The two sides engaged just after midnight, on 19 June. The initial fighting was violent: seven enemy tanks were destroyed on Saumur’s north bridge before it was blown. So as not to be overwhelmed, the French had to destroy a number of bridges: the destruction of Saumur’s north bridge preceded that of the Montsoreau bridge and the railway bridge. Throughout the night, the enemy harassed the French positions.

At daybreak, fighting took place all along the front. The enemy bombarded the French, whose lack of artillery was cruelly felt. Having crossed the river with a small number of men, Lieutenant de Buffévent was killed while destroying a German battery. Everywhere, the squadrons readied themselves for an attempt by the enemy at crossing the Loire, as its preparations intensified.

All day, German artillery batteries and self-propelled guns pounded the French positions, which could not destroy them with their 81 mm mortars. It was a heroic fight: despite inadequate weaponry, the French annihilated everything that came within reach and, in late afternoon, finally blew the Gennes bridge to the north and the Saumur bridge to the south. However, not a single French detachment fell back: the defenders of the island of Saumur still held their positions.

The Balbigny bridge over the Loire as it collapses, June 1940. Public domain

At 9 pm, the German 77 mm artillery and armoured vehicles bombarded the island of Gennes and the southern bank of the Loire, to prepare the ground for crossing the river to the east and west of the island. French machine-gun fire forced them to abort this plan. The enemy was driven back by the effective defence of Lieutenant Desplats’ brigade, which held the island of Gennes. The extremely violent confrontation lasted until 11.30 pm. The Desplats Brigade was nevertheless forced to blow the town’s southern bridge, thereby cutting itself off.

By nightfall, all of the enemy’s attempts at crossing the Loire had failed. The French positions still held: the French units had impressively prevailed against a highly motivated and heavily armed enemy.

At nightfall on 20 June, two companies of infantry officer cadets from Saint-Maixent, who had just been assigned to the Saumur sector, arrived as reinforcements for the French forces positioned west of Gennes.

Throughout the night of 20 June, the Germans pounded the French positions, and in particular Saumur and Gennes, in preparation for crossing the Loire.

A detachment sent from the Poitiers School of Applied Artillery arrived in the sector as reinforcement. One group was positioned at the Port Boulet bridge, which it would hold until evening. But most of the artillerymen were sent backwards and forwards, with no real coordination with the other operations.

At first light, the Germans landed on the island of Gennes, which they succeeded in occupying after hand-to-hand combat. They then attempted to get a foothold on the southern banks of the Loire, but were stalled for several hours by Captain Foltz’s squadron, tasked with defending this sector at any cost. Attacks and counter-attacks took place throughout the day. Overwhelmed, the French were forced to abandon the Gennes sector at around 9 pm on 20 June.

The sacrifice of Lieutenant Desplats, who defended the island with no thought of retreat; the initiative, clear-sightedness and nerve of Captain Foltz, who defended Gennes to the end; the admirable attitude of two of his lieutenants, Roimarmier and Bonnin, killed in the thick of the fighting; and the guts shown by the School’s cadets, who conducted themselves brilliantly despite seeing action for the first time: all contributed to a determined resistance, against an enemy which outnumbered them and was equipped with hefty artillery, tanks and firepower.

Meanwhile, the enemy got a foothold on the southern bank of the Loire opposite Saumur but, despite violent fighting and incessant shelling of the French positions, did not succeed in taking the town. Although the fighting around Saumur, especially the artillery shelling, were the most violent in the sector, the French stood firm and did not evacuate until nightfall.

In the Montsoreau sector, where, according to later reports, a German spy network had been put in place, the order to retreat was given at around 9 pm the same day, 20 June. The brigade defending the site managed to fall back without losing too many men.

On the evening of Thursday, 20 June, the Saumur sector was held in its entirety. But all the reserves were committed and, in large part, spent. The losses were severe.

A wounded German soldier receives medical treatment at the front, June 1940. © German Federal Archives

Inadequate resources and ammunition to carry on an effective defence, coupled with the fact that an armistice had already been requested, meant the evacuation of the Saumur sector became indispensable.

The Cavalry School cadets had been given the mission of standing firm, and they had done so magnificently, sacrificing their lives at the positions they had been tasked with defending, counter-attacking with ferocious energy each time the enemy managed to push through their lines.

Although they were unable to stop the enemy from crossing the Loire, through their heroic resistance the “Cadets of Saumur” – as they were nicknamed by General Feldt, commander of the German 1st Cavalry Division, which led the attack on Saumur – wrote a glorious page in French military history.

French losses amounted to 250 dead or wounded, with 218 cadets and officers of the Cavalry School taken prisoner at the end of the fighting of 19 and 20 June 1940. In the weeks that followed, they were released and allowed to enter the southern zone, even being saluted by the Germans on their way across the demarcation line.