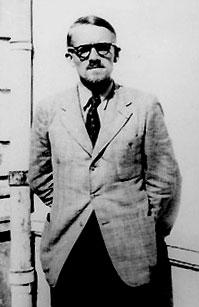

Henry Frenay

Henri Frenay was born in Lyon on 19 November 1905. His father was an officer, as both of his sons were going to be. Frenay belonged to the generation that celebrated France's victory in 1918 and harboured a fierce hatred for Germany. He attended the Saint-Cyr military academy from 1924 to 1926 before serving in metropolitan France between 1926 and 1929 and in Syria from 1929 to 1933, when he returned to France. In 1935 an event occurred that changed the course of Frenay's life: he met Berty Albrecht, an outstanding woman, a major figure in the feminist movement and a campaigner for human rights. She participated in welcoming Hitler's earliest exiles to France. Through her, Frenay became acquainted with another milieu, woke up to the Nazi threat and came to realise that it was much more than an extreme form of pan-Germanism. That is probably why he decided, after attending the War College, from 1937 to 1938, to study at the Institute of Germanic Studies in Strasbourg, where he could observe the Nazi doctrine up close and see how it was being applied in Germany. Frenay realised that confrontation was inevitable, and that it would be a clash of civilisations that would not be anything like the First World War.

Captain Frenay was assigned to Ingwiller when war broke out. He was captured but managed to escape. He rejected the armistice, and in July 1940 wrote a manifesto that was the first call for armed struggle. In December 1940 he was assigned to Vichy, where he briefly worked in the intelligence department. He resigned from the army in February 1941. Frenay went underground to focus completely on building and organising the Resistance that he had been dreaming of since the summer of 1940. Berty Albrecht came to live with him in Vichy and, later, Lyon. They were inseparable until she died in 1943. Frenay organised the earliest recruitments of people who, like him, rejected the armistice. He printed communiqués and, later, underground newspapers (Les Petites Ailes and Vérités) that showed a certain amount of trust in Pétain and a belief that Vichy might have been playing a double game. At the same time, he met Jean Moulin, who gathered information from him about the Resistance and reported it to de Gaulle in London. Then Frenay founded the National Liberation Movement (MLN) and, with help from Berty Albrecht, started putting out a newspaper called Vérités in September 1941. In November, he met the academic François de Menthon, who was head of the Liberté movement, which printed a newspaper with the same name. The MLN and Liberté merged, creating the Combat movement and an eponymous newspaper. It quickly became the occupied zone's biggest and best-organised movement. By 1942, the Vichy police was looking for Frenay. In the summer, 100,000 copies of Combat were printed. That swift growth occurred without any help from the French in London, whom Frenay view with much wariness. Combat did not declare its loyalty to de Gaulle and condemn Pétain's policies until March 1942. On the 1st of October, Frenay was in London to sign his allegiance to de Gaulle. Combat was able to grow and to finance its leadership with funds supplied by Jean Moulin.

Frenay was convinced that the Resistance had to have training in armed struggle and organised the secret army's first cells in the summer of 1942. In 1943, the United Resistance Movement (MUR), which brought together the southern zone's main movements - Combat, Libération and Franc-Tireur - was created under the impetus of Jean Moulin. Frenay was on the MUR executive board. However, the two men clashed with each other. Frenay's independence was strengthened by a legitimacy that owed nothing to no-one, and he chafed at London's financial and political control as well as the increasing bureaucratisation of the homeland Resistance. He created the biggest structured movement - the Secret Army - and the NAP (infiltration of the government) and favoured the MUR's creation, but opposed the reconstitution of political parties, which Moulin wanted to include on the National Resistance Council. For the sake of independence, he also criticised the idea of separating the political and the military. In addition, he was against the idea of a national uprising. General de Gaulle asked Frenay to join the French National Liberation Committee in Algiers. He became commissioner - in other words, minister - of prisoners, deportees and refugees, continuing to hold that post when the government moved to Paris after the Liberation. In that capacity he managed the huge problems posed by the return of French citizens scattered throughout Nazi-occupied Europe. Twenty thousand came home in March 1945, 313,000 in April, 900,000 in May and 276,000 in June. In July, Minister Frenay considered the repatriation over. In November 1945, Frenay started a movement to create what was going to become the Fighting France Memorial at Mont Valérien before resigning from his post.

Frenay's deep disappointment at seeing the old political parties return to domestic squabbling prompted him to embrace the cause of European federalism. In his articles for Combat, Frenay wrote about his dream of a Europe reconciled with itself and with Germany. As president of the European Union of Federalists created in 1946, he did his utmost to convince governments to abandon the framework of the Nation-State, create a single European currency and build a European army. When General de Gaulle returned to power in 1958, Frenay realised that the dream was over. He completely dropped out of public life to write his Resistance memoirs. That very beautiful book, La Nuit (Night), finally came out in 1973. At the time of its publication, Frenay thought he discovered the underlying reasons for his rivalry with Jean Moulin. Until his death in 1988, guided more by resentment than by the quest for truth, he took every opportunity to accuse Moulin of being a "crypto-communist" who would have betrayed de Gaulle and the Resistance. That questionable combat was one too many. The collective memory will not forgive him for it.