1945, horror revealed

Contents

30 janvier : Hitler chancelier du Reich.

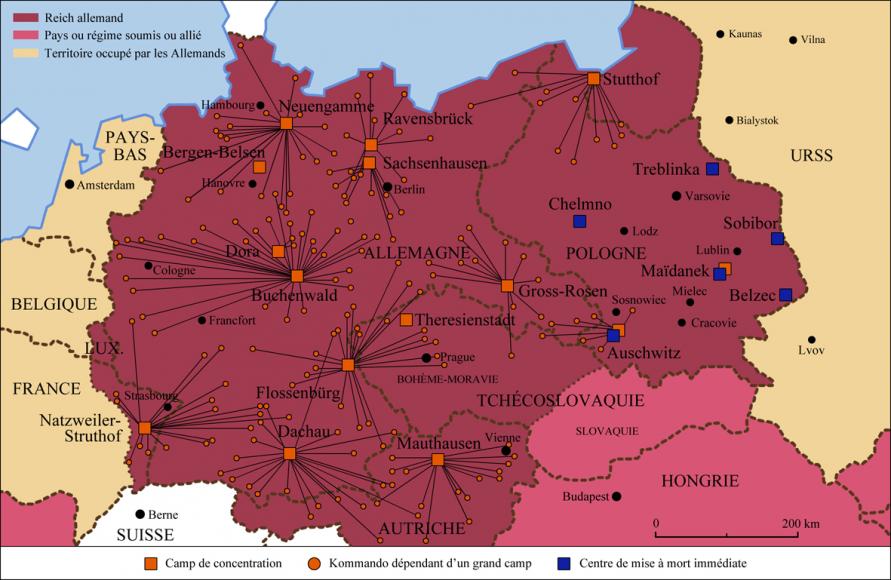

28 février : décret "Pour la défense du peuple et de l’État" : création de la procédure Schutzhaft (détention de sécurité) des Häftlinge (détenus) ; ouverture des premiers camps de concentration.

21 mars : ouverture du Konzentrationslager (KL) de Dachau pour l’internement des déportés "politiques", opposants au régime.

Juin : prise en charge des camps par les SS.

1er août : règlement général des camps de concentration.

15 septembre : lois de Nuremberg sur la discrimination raciale.

Juin : structuration du système concentrationnaire, placé sous l’autorité suprême du SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, chef de l’ensemble des polices unifiées du Reich.

12 juillet : ouverture du camp de Sachsenhausen, en Allemagne.

Janvier : déclaration de Himmler annonçant aux cadres de la Wehrmacht qu’il y a 8 000 détenus dans les camps.

15 juillet : ouverture du camp de Buchenwald, en Allemagne.

Mars : internement massif d’"asociaux" en KL.

12 mars : rattachement (Anschluss) de l'Autriche à l'Allemagne.

2 mai : ouverture du camp de Flossenbürg, en Allemagne.

8 août : ouverture du camp de Mauthausen, en Autriche.

Novembre : passage temporaire des effectifs des KL à 60 000 dont 16 000 Novemberjuden, juifs arrêtés et déportés après la "Nuit de Cristal", premier pogrom nazi contre les juifs en Allemagne.

25 novembre : ouverture du camp de Ravensbrück, en Allemagne.

13 décembre : ouverture du camp de Neuengamme, en Allemagne.

23 août : pacte de non-agression germano-soviétique.

1er septembre : attaque allemande contre la Pologne.

2 septembre: ouverture du camp de Stutthof, en Pologne.

3 septembre : déclaration de guerre de la Grande-Bretagne et de la France à l'Allemagne.

21 septembre : rassemblement des juifs des territoires occupés dans des ghettos.

Octobre : début de l'opération T4 : euthanasie des malades mentaux ; premières déportations de juifs d'Autriche et du protectorat vers la Pologne.

Printemps 1940 : offensive allemande contre le Danemark, la Norvège, la Belgique, le Luxembourg, les Pays-Bas, la France.

Mai : ouverture du camp de Gross-Rosen, en Pologne.

15 mai : capitulation de l'armée néerlandaise.

20 mai : ouverture du camp d'Auschwitz, en Pologne.

28 mai : capitulation de la Belgique.

22 juin : signature de l'armistice franco-allemand à Rethondes.

22 juillet : en France, révision de la naturalisation des juifs depuis 1927.

Août : décret de Heydrich classant officiellement les KL en trois groupes, d'après les catégories de détenus et la sévérité de leur régime de détention : détenus éducables, détenus pour affaires graves, détenus non amendables.

27 septembre : 1re ordonnance des autorités allemandes en France relative aux mesures contre les juifs.

3 octobre : en France, 1er statut des juifs.

30 novembre : Alsace et Moselle officiellement rattachées au Reich.

Mai : ouverture officielle du camp de concentration de catégorie III de Natzweiler.

2 juin : en France, 2e statut des juifs.

22 juin : attaque allemande contre l'URSS.

30 septembre : ouverture du camp d'Auschwitz II (Birkenau), en Pologne.

Octobre : ouverture du camp de Maïdanek, en Pologne.

10 octobre : ouverture du ghetto de Theresienstadt, en Tchécoslovaquie.

Décembre : ouverture du camp de Chelmno, en Pologne.

7 décembre : attaque japonaise sur Pearl Harbor ; entrée en guerre des États-Unis.

12 décembre : promulgation du Keitel-Erlaβ ou Nacht-und-Nebel – Erlaβ, décret Nuit et Brouillard, instituant une procédure judiciaire particulière "visant les éléments hostiles aux forces d’occupation" en France, Belgique, Pays-Bas, Luxembourg, Norvège.

20 janvier : conférence de Wansee sur la mise en œuvre de la "solution finale à la question juive".

Mars : ouverture du camp de Belzec, en Pologne.

Avril : décret du général SS Pohl, dirigeant la section économique de la SS (WVHA), sur l'extermination des détenus par le travail.

Mai : ouverture du camp de Sobibor, en Pologne.

Juillet : ouverture du camp de Treblinka, en Pologne.

2 février : capitulation allemande à Stalingrad.

30 avril : transformation du camp de prisonniers de guerre de Bergen-Belsen, en Allemagne, en camp de concentration.

15 juin : arrivée d'un premier convoi de prisonniers NN norvégiens au KL-Natzweiler.

9, 12 et 15 juillet : arrivée des premiers convois de prisonniers NN français au KL-Natzweiler.

27 août : ouverture du camp de Dora, en Allemagne.

Novembre : fermeture des camps de Treblinka, Sobibor et Belzec.

6 juin : débarquement allié en Normandie.

23 juillet : libération du camp de Maïdanek par les Soviétiques.

30 juillet : décret allemand "Terreur et sabotage" abrogeant le décret Nacht und Nebel.

Août : fermeture de Chelmno.

9 août : ouverture du camp de Vaihingen, en Allemagne.

15 août : débarquement allié en Provence.

Août-novembre : libération de la France et de l'Europe occidentale.

2 septembre : évacuation du camp de Natzweiler-Struthof replié vers Dachau.

23 novembre : découverte du camp de Natzweiler-Struthof par les Américains.

15 janvier : libération de Plaszow par les Soviétiques.

17-19 janvier : évacuation d'Auschwitz et des camps annexes.

25 janvier : évacuation du Stutthof et des camps annexes.

27 janvier : libération d'Auschwitz-Birkenau par les Soviétiques.

28 février : libération de Gross-Rosen par les Soviétiques.

Fin mars : offensive alliée en Allemagne.

4 avril : début de l'évacuation de Buchenwald.

7 avril : libération du camp de Vaihingen par les Français.

11 avril : libération de Buchenwald, sous contrôle de ses détenus, et de Dora par les Américains.

15 avril : libération de Bergen-Belsen par les Britanniques.

19 avril : évacuation de Flossenbürg.

19-29 avril : évacuation du camp de Neuengamme.

21 avril : évacuation de Sachsenhausen.

22-23 avril : libération de Sachsenhausen par les Soviétiques.

23 avril : libération de Flossenbürg par les Américains.

23-27 avril : évacuation de Ravensbrück.

26 avril : évacuation de Dachau.

29 avril : libération de Dachau par les Américains.

30 avril : libération de Ravensbrück par les Soviétiques.

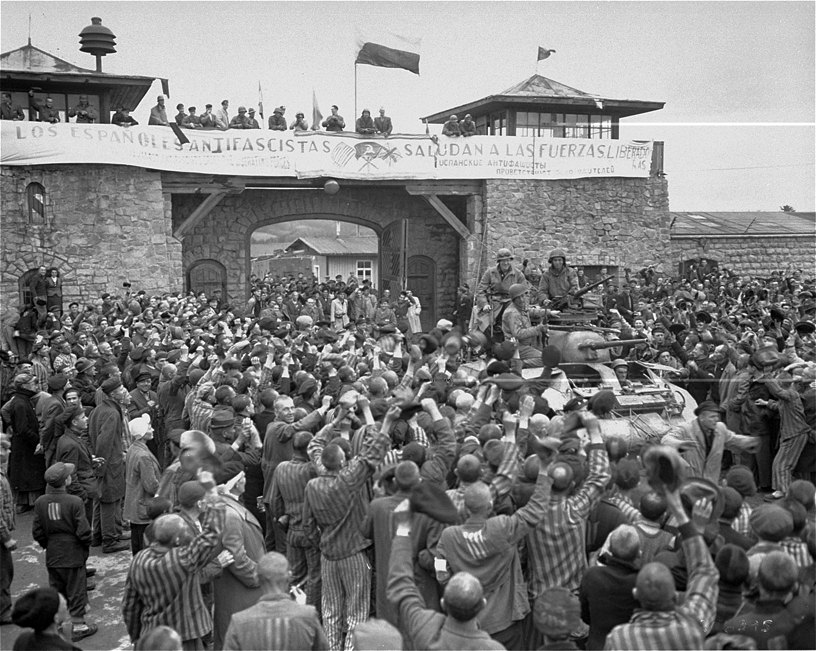

5 mai : libération de Mauthausen par les Américains ; découverte de Neuengamme par les Britanniques.

6 mai : libération d'Ebensee par les Américains.

8 mai : libération de Theresienstadt par les Soviétiques.

7-9 mai : capitulation sans condition de l'Allemagne, à Reims puis à Berlin.

Summary

DATE : 24 July 1944-8 May 1945

LOCATION : Europe

SUBJECT : Liberation of the camps

FORCES PRESENT : Allied troops

SS

In the first months of 1945, the Allied armies liberated the Nazi camps one by one and discovered the scope of the massacres. In April, pictures of the horror were transmitted around the world and the survivors' repatriation was organised. Yet it took years to understand the reality of the concentration camp system and uniqueness of the genocide.

"The gates of hell have opened", American journalist John Berkeley wrote in May 1945. Horror sums up the discovery of the Nazi camps by the Allied armies. The event was the starting point for many stories, often highlighting the exceptional case of Buchenwald, where the prisoners took up arms to free themselves and expel their SS guards. A minority of the prisoners were lucky enough to be liberated under the agreements signed between the SS and the Red Cross, thus avoiding the deadly camp evacuations. But the most striking realities are those of the prisoners who were executed or left on the roadside or elsewhere, exhausted, and discovered by chance by the Allied troops, without a fight. Under these conditions, the repatriation of the prisoners was organised in an improvised manner. The event was nonetheless the source of understanding about the camps and déportations.

La 11e division blindée américaine entre dans le camp de Mathausen, 6 lai 1945 (reconstitution).

© Donald R. Ornitz/collection USHMM, Washington

THE SHOCK OF THE DISCOVERY OF THE CAMPS

At the end of July 1944, the war was not yet over and the Soviets entered the empty Lublin-Majdanek camp, where the gas chambers were still in place. At the end of November, the Americans and the French liberated the Natzweiler-Struthof camp, deserted by its SS guards and its detainees. The same situation was found at Auschwitz in January 1945, although a small number of prisoners were still there.

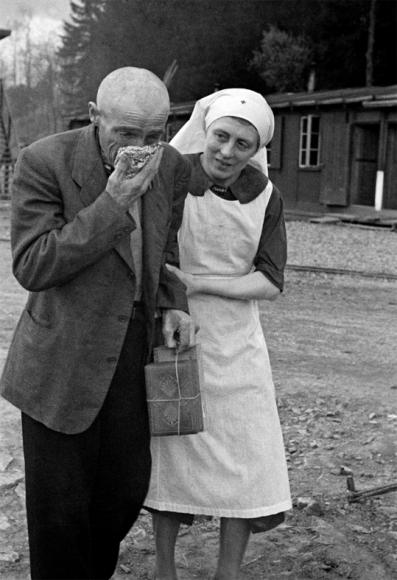

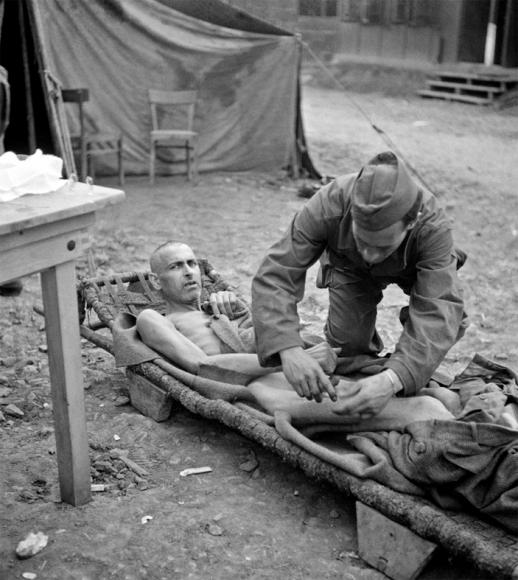

Un soldat britannique parles avec un détenu, Bergen-Belse, 17 avril 1945.

© Sgt Oakes/IWM, Londres

In liberated France, the press, which was unable to verify the information received and was still being censored, published little or nothing on the subject, notably so as not to frighten families awaiting the return of a loved one. L'Humanité dedicated two articles to the discovery of the camps in December 1944, then nothing until 5 April. Le Figaro published a paper on Struthof on 3 March 1945, three months after the camp was discovered. Even then, these articles were not "Front Page" material. The same discretion applied to the radio and cinema newsreels, which is why people were all the more stunned when the stories and photographs of this horror were published.

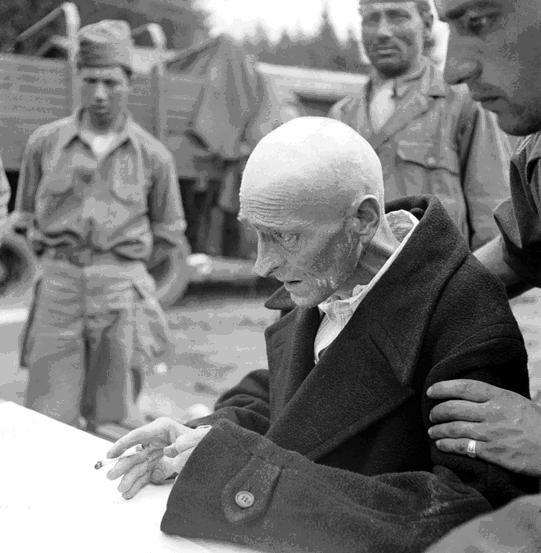

At the start of April 1945, first the Kommandos at Neuengamme were discovered. On 5 April, entry into the Ohrdruf camp, in Thuringia, presented the horror of the situation. More than 3,000 bodies lay there, naked and emaciated. On 11 April, the Americans entered the "little camp" of Buchenwald, a veritable slaughterhouse, from which convoys had left for Dachau during the previous days. Many prisoners were so exhausted that they barely understood that they were free. The sight of Boelcke Kaserne in Nordhausen, where the sick from Dora were parked, was another horrible scene: 3,000 bodies and 700 dying survivors. On 14 April, the carnage at Gardelegen was discovered, a little village where over 1,000 detainees were sent on a death march after the Kommandos evacuated Dora and were burnt alive in a barn. The next day, the British liberated the Bergen-Belsen death camp, where thousands of people were dying amidst the many cadavers. On 29 April, the Americans entered Dachau and discovered over 2,300 dead bodies in the station, left in a train that had arrived from Buchenwald. Faced with this horror, some soldiers could not stop themselves from killing the SS guards. In all, it is estimated that one-third of the 750,000 detainees in the concentration camp system died during the last weeks of the war, in the camps or during what the detainees called "death marches".

The Allied High Command was quickly informed of these terrible discoveries. On 12 April, Eisenhower, accompanied by Patton and Bradley, was at Ohrdruf. That very day, he decided to broadcast the news to all the press, even asking his troops nearby to come and witness the atrocious chaos. "We are told that the American soldier doesn't know what he is fighting for. Now, at least, he will know what he is fighting against," he declared. Visits were organised for journalists and parliamentarians a few days later. From then on, the lockdown of censorship was blown apart: the images of this horror, filmed or photographed, were legion. The aim was to show all the horror, to make it a "lesson". The American cameramen of the Signal Corps received strict instructions for filming the atrocities, the camps and the people who were there. Several war correspondents who saw these sites were also highly talented photographers – Margaret Bourke-White (of Life, at Buchenwald), Lee Miller (of Vogue, at Buchenwald and Dachau) and Eric Schwab (a Frenchman, at Ohrdruf, Buchenwald, Thekla and Dachau).

"The entire world has to know," said Sabine Berritz in the newspaper Combat of 3 May 1945. "Should we tell these horrifying stories?" she wrote. "Should we let our children see this mass of crimes? In the past we would have said no. We would have spoken out against the distribution of such atrocious documents. […] But now, the reviews and newspapers here and around the world must publish these stories and these photos. That is why, despite our repulsion, we must show them to our children, to all children. These abominable memories must leave a mark on their memories […]". The images of bulldozers pushing bodies into the mass graves at Bergen-Belsen were largely distributed. The French press which, up until then, almost never talked about the camps took up the subject in the second half of April 1945: three-quarters of the articles were dedicated to their discovery between mid-April and mid-June.

All the pictures published are pictures of absolute horror. They left their indelible mark on our consciences. With their power and their number, they form a veritable threshold, the threshold of how we represent mass murder. As Clément Chéroux demonstrated, if Word War I had shown death, it was still "individual" and it was mainly "that of the enemy". "It had nothing to do with the collective, mass murder of the camps, with piles of cadavers filling up the images" in 1945.

LIFE AND DEATH IN THE LIBERATED CAMPS

The progression of and reactions to "liberation" during the following weeks varied greatly from one deportee to another. But for most of them, those days were first and foremost difficult and deadly given how poor their health was and how catastrophic the sanitary conditions were.

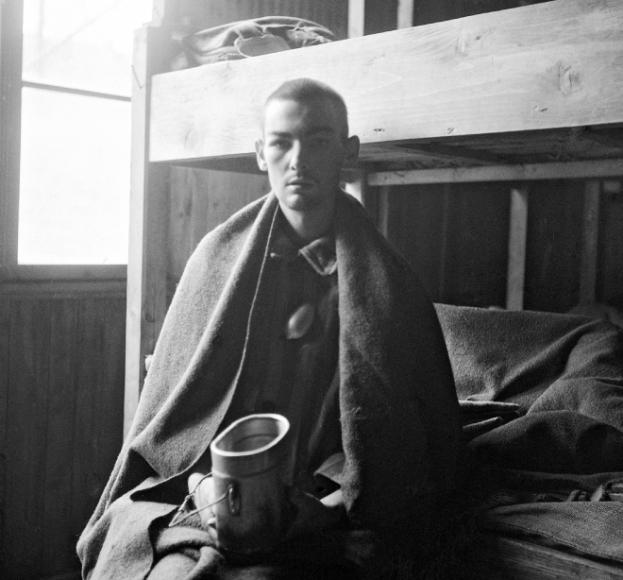

At Dachau, for example, there were widespread epidemics. One week after the camp was liberated, not all of the bodies had been buried despite the requisition of neighbouring residents. In May, despite the measures taken by the American troops, over 2,200 people continued to die there. And yet, these first hours and first days of freedom were also intense. The extraordinary photographs that the Spanish prisoners at the Mauthausen camp immediately took bear witness to this. They took them first of all to record the event, like the reporters who came to testify to the horror. Detainees thus had pictures taken of themselves showing characteristic features of the camps. But it was mainly a thirst for life and the winds of newfound freedom that these snapshots show. They capture groups of friends, sometimes posing with their weapons, symbols of the victory of a community of survivors. Many snapshots concern men photographed alone, thus regaining their stolen individuality.

The signs of their past dehumanisation have disappeared – they are wearing new civilian clothes, their matriculation numbers torn off… – or, on the contrary, are parodied – some are imitations of their old identity photos taken in the camps, but next to their matriculation number they now ostensibly show their name. Many people were then thinking about the future and the societies to be rebuilt, learning the first lessons of the tragedy that had just ended. At Mauthausen, on 16 May 1945, as in most of the liberated camps, an International Oath in recognition of the liberators, brotherhood and hope was pronounced. The declaration of the Comité Français de Libération du Camp (French Committee of the Liberation of the Camp) launched a call to the community of "citizens of the great allied people before whom is opening the amazing future of collective society, national elevation and individual development." Newspapers with evocative titles, such as Liberté (that of the French at Dachau), were founded.

During those first days of freedom, detainee organisations were set up in most of the camps to organise everyday life before their repatriation and to prepare for their return. At Dachau, an International Prisoners Committee (IPC) took on the difficult task of assisting the American army in managing an enclosure that still contained more than 30,000 people who had to be clothed and fed. Many administrative formalities were necessary, first of all to give identity papers to everyone. The IPC also drew up the first lists of the dead. The Americans also demanded that a strict security service be set up to maintain a health quarantine – and therefore an interdiction to leave the camp – and impose compliance with the rules: no cooking in the Blocks, no degradation to the buildings for making fire, etc. Many detainees did not understand all these restrictions, especially having to wait several weeks before being allowed to go home.

Barbelés et baraquements du camp d'Auschwitz, Pologne, 1945.

© Mémorial de la Shoah

REPATRIATION TO FRANCE

In Algiers, starting in November 1943, Free France set up a commissariat to deal with displaced persons. This was entrusted to à Henri Frenay, founder of the “Combat” resistance movement. After the Liberation he became the minister of prisoners, deportees and refugees, in charge of organising the return to France for all the "Absents". Nearly 950,000 prisoners of war, over 600,000 forced labourers and tens of thousands of deportees were in Germany, awaiting repatriation. Documents and large archives from the camps and prisons set up in occupied areas were retrieved to round out the information that had so far been rather patchy. Starting in February 1945, French repatriation missions made it easier to locate victims. A decree dated 3 November 1944 officially ordered a census of the war victims in order to understand the number of repatriated prisoners to be handled.

But, at the time of repatriation, Frenay's ministry largely depended on the Supreme Headquarter Allied Expeditionary Forces – SHAEF – and its margin of manoeuvre was reduced in the end. Heavy constraints were thus placed on the very organisation of their return: war prisoners were emphasised by the Anglo-Americans; a quarantine was placed on people who, in the meantime, have to stay on site; health inspections and identify checks take place at the borders. Thus, the repatriation "scenarios" differed widely depending on the liberation site: they worked fairly well for those who were returning from Buchenwald, but it was more complicated for the former deportees from Dachau, Flossenbürg and Bergen-Belsen.

The first returns of freed war prisoners and deportees by the Soviets took place in March 1945 in Marseille, by ship from Odessa. The first women from Ravensbrück reached the Gare de Lyon in Paris on 14 April, welcomed by General de Gaulle. Their comrades liberated thanks to the Swedish Red Cross's work returned home via Sweden. Most of the prisoner returns were centralised in Paris: the Gare d'Orsay for those arriving by train, Bourget Airport for those returning by plane (the sickest deportees and personalities). Given the physical and mental condition of the returning deportees and following the revelations in the press on what was discovered in the camps, a large reception centre was set up at Hotel Lutétia at the end of April, with medical and administrative services. Nonetheless, many deportees criticised the complexities and missteps of an administration that they said had not taken into account what they had undergone.

And yet, as Robert Belot pointed out, based on Bilan d'un effort (Assessment of an Effort), the summary presented by Frenay when he left the ministry, "the system appears to have been effective since, in less than ninety days, two-thirds of the liberated people were repatriated. During the year of 1945, in a totally disorganised country, more than 1,500,000 men, women and children were repatriated in less than one hundred days. The people repatriated received a stipend and clothes […] and received free medical care. The country's overall financial effort was considerable: 20% of civilian expenditure for the year 1945 according to the figures in the Bilan." On 1 June, the millionth repatriation was celebrated: Jules Garron, a war prisoner.

AN INITIAL UNDERSTANDING OF THE CAMPS

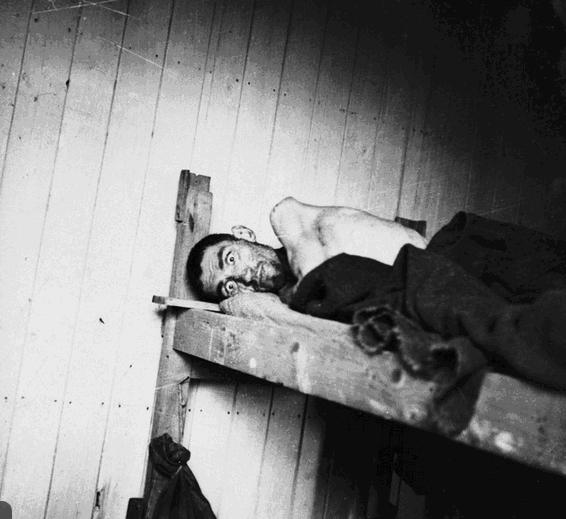

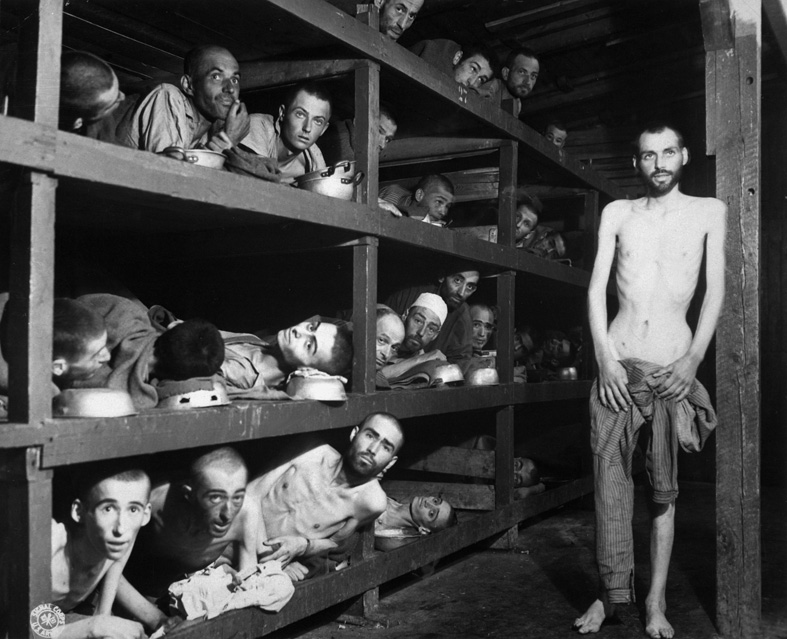

Intérieur d'une baraque du petit camp de Buchenwald, 16 avril 1945.

© Harry Miller/collection NARA, Washington

Pictures of the discovery of the camps are the first "source" of information revealing the existence of the world of the concentration camp. But the horror that was shown, given its vast scope, outweighed any detailed analysis. These photographs are, at the end of the day, not very precise and give a poor picture of the reality in the camps. The front page of L'Humanité dated 24 April 1945, for example, presented an article on Birkenau with a picture of Bergen-Belsen captioned "Ohrdruf". These photographs fixed an image of a concentration camp system that was breaking down: many detainees had been thrown out onto the roads in the face of the Allied advances in deadly "death marches". These snapshots do not show their usual operations: the discipline, humiliations, forced labour, etc. The purpose of the deportations can be summed up by the mass graves discovered, which notably did not report on the genocide of the Jews of Europe. Minister Frenay's speech on the return of the "Absent" also encouraged a global approach to the "deportees", contributing to the misunderstanding of the specificities of Nazi policies.

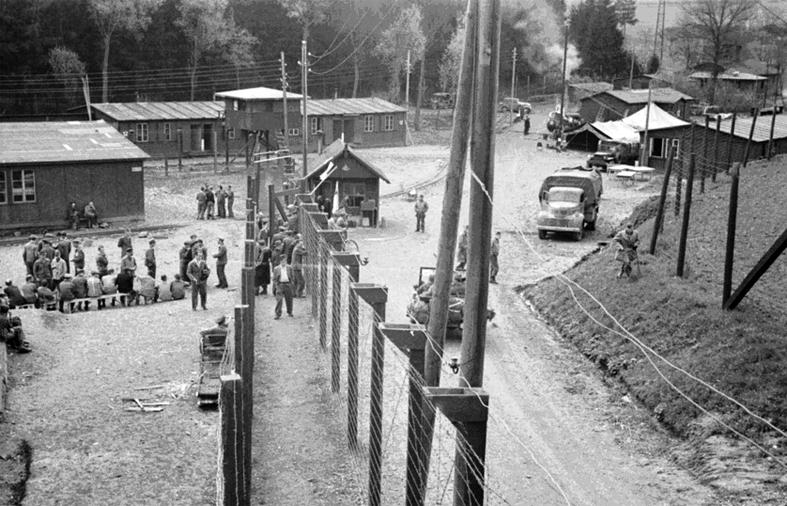

Devant le camp de concentration de Dachau, Allemagne, mai 1945.

© ECPAD/Pierre Raoul Vignal

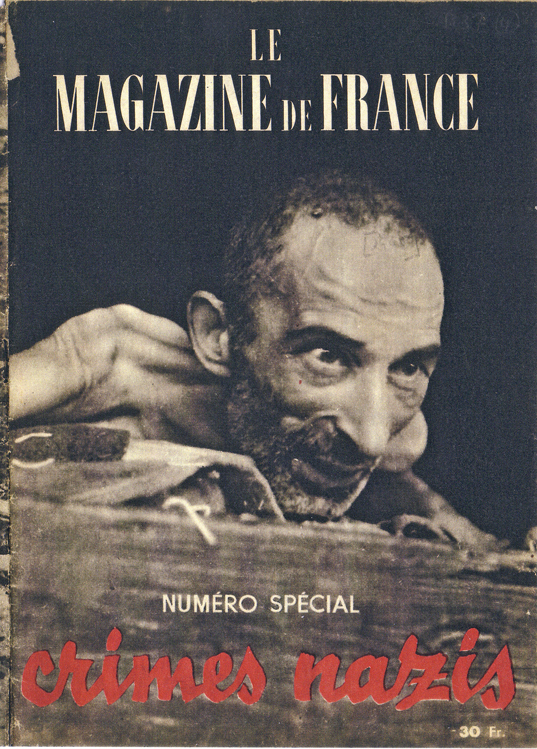

Couverture de "Magazine de France", numéro spécial consacré aux crimes nazis, été 1945.

© Collection Musée de la Résistance nationale, Champigny-sur-Marne

And yet, even though we must not forget its weak dissemination, an understanding came out of the first months after the discovery of the Nazi camps. Along these lines, the genocide of the Jews, often summed up as a "great silence", was significant. We can provide details of this by presenting the various vectors of our understanding of the camps. This understanding firstly comes from the deportees themselves: nearly 210 testimonials were published between 1944 and 1947. Those of Jews, few of whom returned, are obviously rare. Furthermore, as Annette Wieviorka showed, these stories did not much interest a society that, overall, was not ready to hear them. The associations of victims that were set up started the work of transmission that continues to this day. Annette Wieviorka points out that, despite their imprecisions, the Jewish associations made "considerable progress toward truth". Excerpts from the Vrba and Wetzel report on Auschwitz were published by their newspapers. Moreover, the Centre de documentation juive contemporaine (CDJC – Contemporary Jewish Documentation Centre) undertook an impressive work for understanding the genocide, notably thanks to a collection of scientific works.

Le général de Gaulle accueille des rescapées de Ravensbrück, avril 1945.

© Mémorial de la Shoah/CDJC

The search for and judgement of Nazi war criminals was also an opportunity to bring together essential components. The first summaries by the Ministry of Justice's Research Department or those provided by the General Intelligence were, in several cases, already precise. At the International Nuremberg trials, in their inaugural indictments, prosecutor Robert Jackson talked about the murder of 60% of Europe's Jews, or 5.7 million dead, before presenting the "Nazi plan" to annihilate "the entire Jewish people" during the following sessions. "History has never recorded such a crime, perpetrated with such premeditated cruelty against so many victims", he concluded, quoting, for example, a report from the Einsatzgruppe A dated 15 October 1941 on the extermination of Jews in Lithuania.

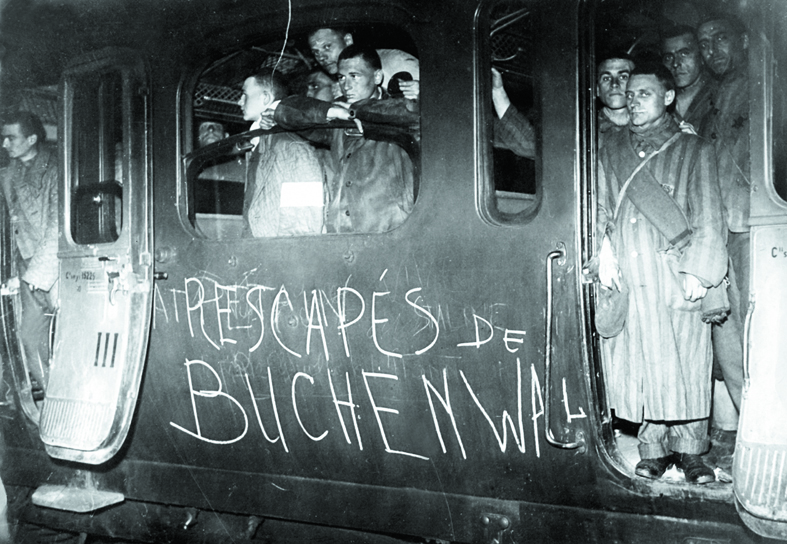

Retour vers la France de rescapés de Buchenwald, 1945.

© Service historique de la défense

The State is often absent from this picture, having seen nothing and not wanting to see the unique nature of the genocide. And yet, the missions from the Frenay ministry of repatriation and the census, later of reparation and recognition of the victims, were organised to better understand them, with all their special features. At the sub-directorate of Intelligence – then of Research – and Documentation, a "deported Israelites" section, directed by a former internee at Drancy, François Rosenauer, began working in the autumn of 1944 to take a census of Jewish deportees and the convoys in the "final solution". Notably thanks to the part of the Drancy file that was found, good results were quickly achieved: on 23 July 1945, for example, Minister Frenay announced the figure of 66,576 deportees from Drancy, an assessment that was nearly exhaustive. Already at that date, the ministry knew that the vast majority of these people were Jews murdered at Birkenau. One of the rooms of the "Crimes Hitlériens" exhibition that opened in Paris in June 1945 used this work to offer a chronology of persecution and deportation. Roger Berg's book, La persécution raciale, in the "Documents pour servir à l'histoire de la guerre" (Documents Serving the History of the War) series put out by the State, is another illustration.

Even though it would take years longer to grasp the full scope of the criminality deployed by the concentration camp system and the unique aspect of the genocide of Europe's Jews, an initial understanding came out of the camps immediately after the war. After the shock, sources and analyses began to irrigate our reflections on the major phenomenon that the Western World discovered with horror in 1945.

Author

Thomas Fontaine – Associate Researcher at the Centre of 20th Century Social History, Paris 1.

Read more

Bibliography:

Déportation et génocide : l'impossible oubli, Thomas Fontaine, Tallandier, 2009.

1945, AnnetteWieviorka, La découverte, Seuil, 2015.

Les Marches de la mort. La dernière étape du génocide nazi, été 1944 - printemps 1945, Daniel Blatman, Paris, Fayard, 2009.

Article on line:

Photo galleries:

Liberation of the Vaihingen camp in Germany

The 2nd DB's advance on the Rhine; liberation of the Dachau concentration camp

Videos :

Evacuation of deportees from the Penig camp to a Luftwaffe military hospital

Liberation of the Nordhausen camp

The liberated Bergen-Belsen camp burns down

Liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp

Articles of the review

-

The event

Natzweiler-Struthof Concentration Camp

Read more -

The figure

A land of the Righteous

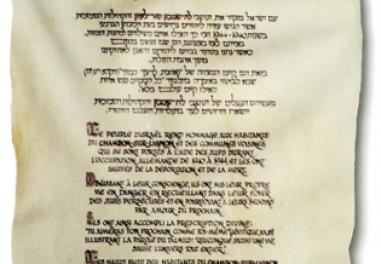

During the Occupation, the residents of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and the neighbouring villages saved many Jews. It was such a unique example of civic and spiritual resistance on such a scale that the town and the region received a diploma of honour from Yad Vashem in 1990.

Read more -

The interview

Georges Loinger

Georges Loinger, now 104 years old, was one of the leaders of the Œuvre de secours aux enfants (OSE – Children's Aid Society) during the Occupation, which organised the rescue of several thousand Jewish children. This great French resistance fighter remembers the reasons behind his commitment and hi...Read more