Luynes National Cemetery

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Click here to view the cemetery's information panel

In the late 1950s, the decision was taken to build a cemetery in Luynes in honour of the soldiers of the French Empire who lost their lives in southeast France in the two world wars.

Work began on Luynes National Cemetery in 1966. It contains the bodies of more than 11 000 French troops killed in the First and Second World Wars: 8 347 in 1914-18, 3 077 in 1939-45.

The bodies buried at Luynes were exhumed from temporary cemeteries in the departments of Aude, Alpes de Haute-Provence, Alpes-Maritimes, Bouches-du-Rhône, Gard, Hérault, Var, Vaucluse and Pyrénées-Orientales. In accordance with the law, families that requested the bodies of loved ones had them returned to them, to be buried in private graves, while the remainder were laid to rest at Luynes: 8 402 in individual graves and 3 022, unable to be identified, in three ossuaries. This process went on until 1968. The cemetery was officially opened on 27 September 1969, by veterans minister Henri Duvillard, a former member of the Resistance, leader of the Corps Francs du Nord du Loiret.

1914-18: the Empire comes to France’s aid

Right from 1914, France called on its empire to support the war effort, by providing troops, workers (nearly 200 000 men) and raw materials. A total of 600 000 soldiers were mobilised from across the Empire: tirailleurs, spahis and zouaves from North Africa; tirailleurs from sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar; and troops from Indochina, the Antilles and the Pacific. From the Marne to Verdun, Champagne to the Aisne, these men fought on the main fronts, including the Eastern Front.

The soldiers from the colonies arrived in metropolitan France via Marseille, while others passed through the port city on their way to the Eastern Front. The camp of Sainte-Marthe was set up in 1915 to accommodate the colonial troops.

Unaccustomed to the cold climate, these soldiers were susceptible to respiratory illnesses and frostbite. The violence of the fighting, the bad weather conditions and the poor hygiene of the trenches caused the deaths of more than 78 000 of them.

In winter, the colonial soldiers were withdrawn from the front and sent mostly to the South of France. The French Army’s many wounded and sick who were evacuated from the different fronts, and in particular the colonials, were also treated in the south. Despite the treatment they received, several thousand died in hospitals of the region and were initially buried in local cemeteries. Some 8 347 bodies (2 626 of them in ossuaries) were reburied at Luynes.

1939-45: the French Empire in the war

As in the First World War, France called on the troops of its Empire in September 1939, when France mobilised and declared war on Nazi Germany. Alongside their French comrades, the colonial soldiers distinguished themselves in many battles. Among them, the Senegalese tirailleurs (who despite their name came from across sub-Saharan Africa) fought particularly fiercely. Besides sustaining severe losses, they sometimes suffered reprisals at the hands of German troops who, exasperated by their resistance, hounded them relentlessly. Thus, they were the victims of summary executions, for instance at Chasselay (Rhône) or Chartres, where survivors of the 26th Regiment of Senegalese Tirailleurs were massacred, a crime denounced at the time by prefect Jean Moulin.

From July 1940 onwards, as certain territories of the Empire came out in support for Free France (in particular, French Equatorial Africa), countless volunteers from all backgrounds enlisted in General de Gaulle’s Free French Forces. They particularly distinguished themselves at the Battle of Bir Hakeim (Libya), in June 1942, against Rommel’s Italian and German troops.

After the Anglo-American landings in North Africa (November 1942), the French Army of Africa made its re-entry into the war against Germany and Italy. It took part in the Tunisian campaign, which culminated in enemy surrender in May 1943, liberated Corsica in September and, from November, played an active role in the Italian campaign, as part of the French Expeditionary Force commanded by General Juin. The North African tirailleurs, spahis and goumiers distinguished themselves on the slopes of Mount Belvedere (February 1944) and opened up the road to Rome during the victorious Garigliano campaign, in May 1944.

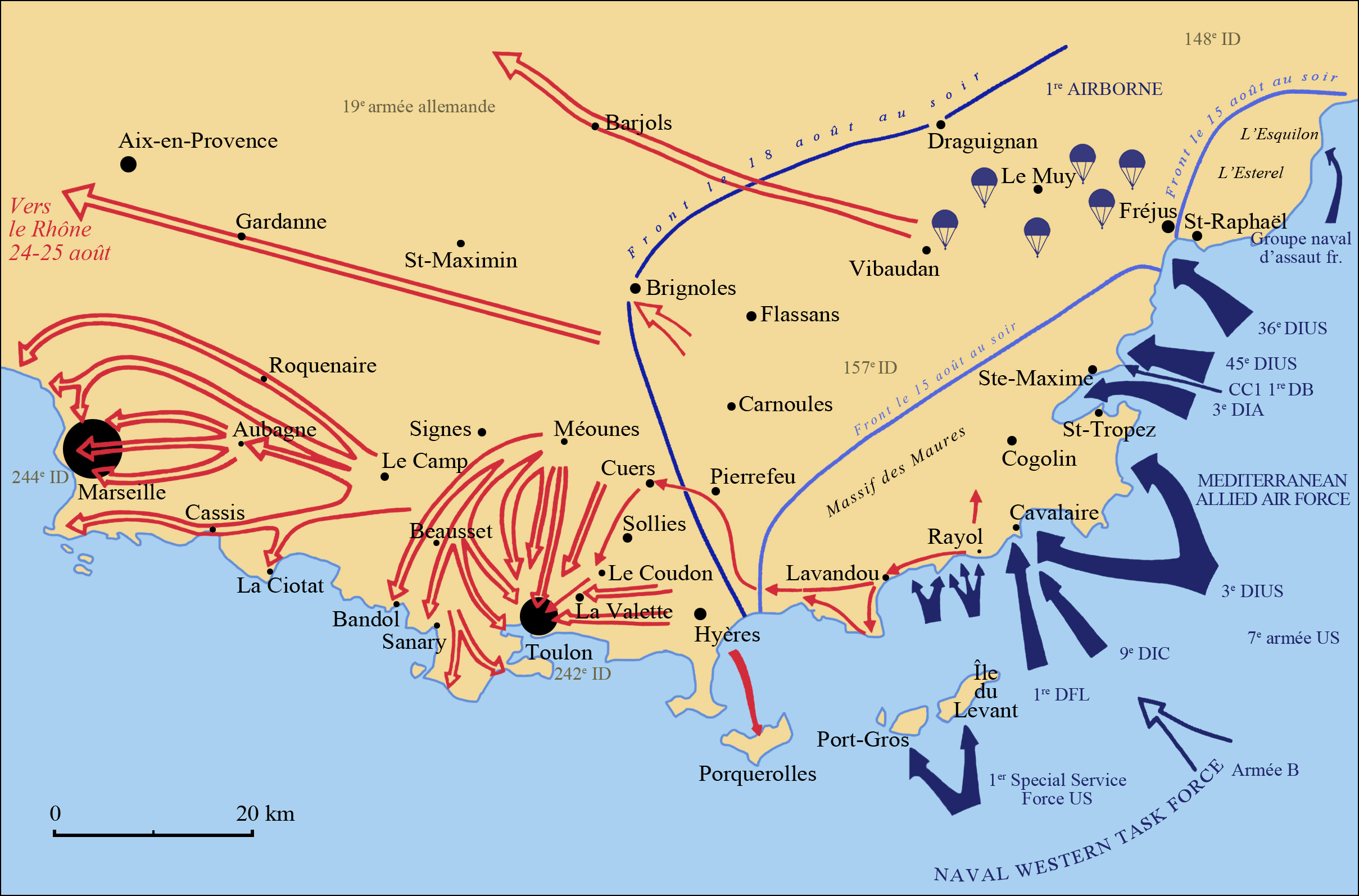

On 15 August 1944, two months after Operation Overlord in Normandy, the Allies landed in Provence. General de Lattre de Tassigny’s Army B (the future French First Army) consisted predominantly of African soldiers. Following violent fighting, on 28 August 1944 they liberated the ports of Toulon and Marseille. These deep-water ports were crucial to maintaining supplies to the Allied armies in France. Ascending the Rhone valley, the French First Army took part in the Battle of the Vosges and the offensive against Belfort (Autumn 1944), where goums and tirailleurs sustained major losses, owing to enemy resistance and bad weather. Even so, during the winter of 1944-45, these men liberated Alsace. Crossing the Rhine, on 31 March 1945, the First Army drove deep into Nazi Germany and entered Karlsruhe and Stuttgart.

Most of the soldiers killed in the Second World War and buried at Luynes (3 077 men) died in the fighting to liberate Provence, following the landings of 15 August 1944.

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © ECPAD

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Nécropole nationale de Luynes. © Guillaume Pichard

Senegalese tirailleurs train at the 3rd Colonial Infantry Division training camp, 1917. In spite of their name, the “Senegalese” tirailleurs were not only from Senegal but from all the French colonies in sub-Saharan Africa. In the two world wars, soldiers from across the Empire (North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, Indochina) were mobilised and fought in metropolitan France. © ECPAD

Senegalese tirailleur resting, 1917. © ECPAD

Senegalese tirailleurs of the Second Army pass through a village, 1940. © ECPAD

Moroccan goumiers during the Tunisian campaign, March 1943. The Anglo-American landings in North Africa (Operation Torch, November 1942) led to the French Army of Africa rallying to the Allied cause and re-entering the war. It was rearmed by the Americans and sent to fight in the Tunisian campaign, until the German surrender of May 1943. © ECPAD

Soldiers of the 6th Regiment of Moroccan Tirailleurs, 4th Moroccan Mountain Division, march to the line in Italy, February 1944. A French Expeditionary Force, commanded by General Juin, participated in the Italian campaign, distinguishing itself in particular in the winter of 1943-44 (capture of Belvedere) and at Garigliano (May 1944). © ECPAD

Landings of 15 August 1944 and Battle of Provence. © MINARM/SGA/DPMA/Joëlle Rosello

Tirailleurs of the 3rd Regiment of Algerian Tirailleurs (3rd Algerian Infantry Division) are cheered by the people of Marseille, August 1944. After violent fighting, the troops of General de Lattre de Tassigny’s Army B liberated Toulon and Marseille on 28 August. © ECPAD

At Maximiliansau in Germany, a tirailleur of the 3rd Regiment of Algerian Tirailleurs keeps watch over the Rhine from his lookout post, March 1945. Following the Battle of France, marked by fierce fighting in the Vosges, Franche-Comté and Alsace (October 1944 to February 1945), French troops entered Germany and crossed the Rhine on the night of 30 to 31 March 1945. © ECPAD

Moroccan goumier on horseback in the ruins of Büchelberg, Germany, March 1945. © ECPAD

Practical information

Luynes

Read more

Read more

Comité départemental du tourisme des Bouches-du-Rhône

13, rue Roux de Brignoles

13006 Marseille

www .visitprovence.com