Bobigny: from ruins to remembrance site

For some years now, the town of Bobigny has wanted to showcase the site of its former deportation train station by means of a landscape and scenographic development programme. The goal of the project is to reveal a little-known historic remembrance site to the general public, while preserving its original topography and integrating it with the urban landscape.

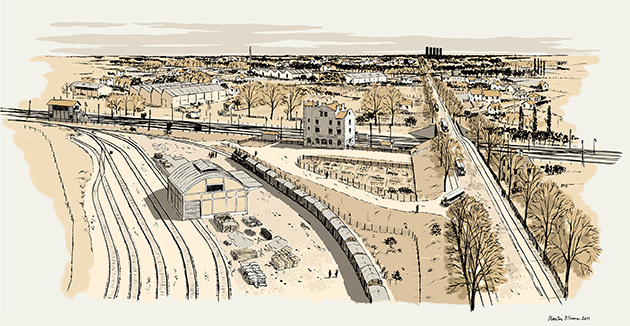

Drawing of Bobigny railway station. © E. Martin / Ville de Bobigny

Originally just an ordinary railway station in the Paris suburbs, set in a landscape of small suburban houses and farmland, between July 1943 and August 1944 it was the starting point for the deportation, in 21 convoys, of over 22 500 French Jews from the nearby Drancy camp. As Ida Grinspan tells in her account of her deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau from Bobigny station on 10 February 1944, this “little old station” was, for many, their “last glimpse of a civilised world”.

FROM A SUBURBAN RAILWAY STATION TO A DEPORTATION STATION

The first thing you see is the main station building, built in 1928 to a rationalist design borrowed from the stations of the Saintes-Royan line, in Charente-Maritime. The building was used by rail passengers only until May 1939, when it was closed due to insufficient traffic. It was then used to house railway workers from the freight station, which continued to operate throughout the occupation.

The freight station’s operations were centred around the market hall, built in the early 1930s to facilitate relations between private branch lines and the northern and eastern rail networks. It served the military fort of Aubervilliers and the surrounding factories, including the printing house of newspaper L’Illustration, and also the market gardeners of Bobigny and the surrounding area. The market hall comprised an open-air platform, storage areas, parking tracks, technical facilities (weighing scales and crane), and offices. But in 1943-44, that platform was “overrun with grey uniforms” herding deportees into goods trucks, tells Simone Lagrange, deported on 30 June 1944. A discreet hall on an industrial site closed to the public, less exposed than that of Bourget-Drancy, which was used to assemble deportation convoys from spring 1942 until summer 1943, a railway line connected to the eastern rail network, so that the trains could be left standing on the tracks for hours on end: the site had all the right characteristics to make Bobigny the new point of departure for the deportation of French Jews, in the eyes of Aloïs Brunner, whom Eichmann had entrusted, in June 1943, with organising the “Final Solution” from occupied France.

The former Bobigny deportation station. © H. Perrot

So, beginning with convoy number 57, formed on 18 July 1943, the trains departed from Bobigny station, which thus became an accessory to the genocide of European Jews. The new logistics implemented by Brunner relied on the site in conjunction with the Drancy camp, installed in the Cité de la Muette housing estate. During the occupation, the estate’s great tower blocks, now demolished, could be seen in the distance from Bobigny. This was where the deportees began their journey, piling into buses that took them to the station. They arrived at the site by the Route des Petits Ponts, present-day Avenue Henri Barbusse; the buses drove along an access way, up a ramp and into a paved yard in front of the station building. A fence separated this part of the site from the freight station and, after passing through the gate, the buses parked alongside the train, which stood on the track before the market hall, having usually arrived the day before. The trains usually comprised at least 20 goods trucks, which were often made to accommodate 1 000 deportees. Carriages and trucks were added for the SS escort and their baggage. When the whistle blew, the train would pass the signal box on the edge of the site and join the Grande Ceinture line, before setting off towards Noisy-le-Sec junction and the eastern rail network.

A CEREMONIAL SITE

In addition to the railway lines and buildings, other marks were left after the war: industrial remains, because the site went on being used; and commemorative plaques recalling the tragic events that took place here. The SNCF went on using the site until the late 1970s and, from 1954 onwards, areas of the freight station were let to a scrap metal company. In the 1980s, the firm took over the whole site, which it occupied until the early 2000s. The access way was closed off and a huge promontory was built, from which to tip the scrap metal into the open goods trucks standing on the same track used during the occupation. This explains the long grey retaining wall opposite the market hall. It was therefore at the heart of a working scrap yard, among heaps of scrap metal, that the first ceremonies to remember the victims took place at Bobigny, in the 1970s.

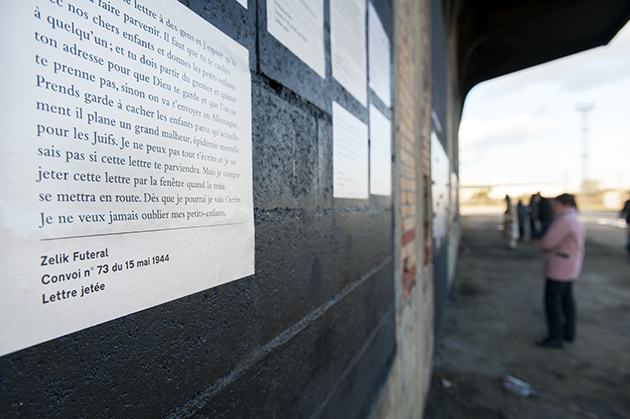

The former Bobigny deportation station. © H. Perrot

The first had been held at Drancy immediately after the war, when victims’ families and organisations and the Jewish Consistory remembered the deportations. At Bobigny, three plaques were unveiled on the station building in 1948 by deportee organisations, the veterans minister and the SNCF chairman. They paid tribute to the 100 000 deportees who “departed from this station” – an inaccurate figure, therefore – “most of whom died in the Nazi death camps”, and to railway workers who belonged to the Resistance. They made no mention of the fact that those deported from this station were exclusively Jews, or identified as such by the Nazis and murdered. The main commemorations of the genocide then moved to the Memorial to the Unknown Jewish Martyr, on Rue Geoffroy l’Asnier, in Paris, and were resumed in Drancy, before the statue by Shlomo Selinger, in 1976. At Bobigny, the industrial activity prevented a commemorative ritual from being put in place and hindered each ceremony. In 1992, the town council unveiled a new plaque on the station building, this time making explicit reference to the more than 22 000 French Jews deported from the station; meanwhile, another plaque, commissioned by the Association of Families and Friends of the Deportees of Convoy 73, specifically remembered the victims of that particular convoy, which left on 15 May 1944 for the Nazi-occupied Baltic.

The former Bobigny deportation station. © H. Perrot

PRESERVING THE TRACES IN AN URBAN ENVIRONMENT

For a long time, the echo left by this site, and by all of its architectural, industrial and commemorative traces, was not loud enough to prompt the emergence of a remembrance site. About ten years ago, the town council launched a serious discussion about what status should be given to the site and the need to preserve the traces it contains and, more particularly, to give them resonance, in the entirely transformed and more densely built-up urban fabric of the surrounding area.

These traces are typically not integrated with memorial structures. They are at the heart of the planned development of Bobigny’s former deportation station, led by the town council with support from the Ministry of the Armed Forces, the Île-de-France regional authority, the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah and the SNCF. Through outdoor visits of a site that has been largely preserved throughout its history and is centred on the memory of the deportation of French Jews, the idea is to shed light on these fragile materials, put them in perspective and ensure their lasting legacy, so as to aid our comprehension of the events that took place here. This means creating a sensory tour that evokes the memory of the victims and explains the ideology and processes that led to the genocide.

Visitors will hear the words of poet Benjamin Fondane, deported from Bobigny on 30 May 1944, imagining he was a “clump of nettles under [our] feet” and addressing the citizens of tomorrow who would soon discover the site of Bobigny: “when you trample on this clump of nettles that had been me, in another century, in a history you will think outdated, remember only that I was innocent and that, like you, mortal that day, I, too, had had a face marked by rage, by pity and joy, quite simply, a human face!”

Thomas Fontaine, historian and curator of the preview exhibition of the former Bobigny deportation station