The landscape, a place of military strategy

Prior to any analysis of the reconstruction and redevelopment of landscapes post-conflict, it is worth looking at what the landscape represents to soldiers who make it the theatre of their confrontations with the enemy. An object of war, the landscape quickly becomes the subject of war, requiring belligerents to use their environment and its constraints, and to incorporate them in their overall military strategy.

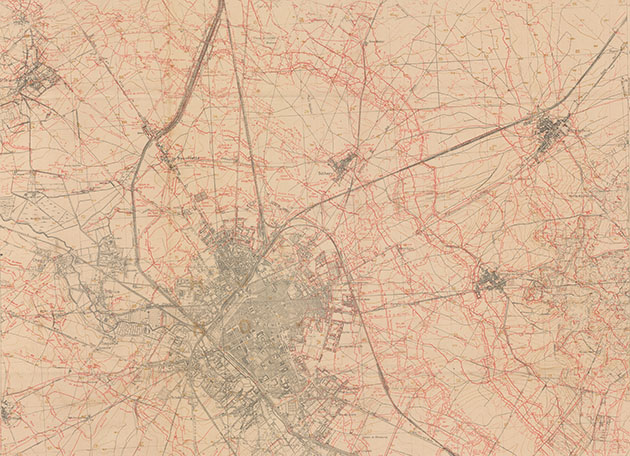

Topographical map, in an edition of 6 October 1918.

In red are the networks of French and German trenches around Reims. © Collection N. Jacob

In the beginning was the battlefield, which is to say an actual field, with an area demarcated for combat, determined both by the range of the weapons and the numbers of troops involved. This almost ritual terrain, from Marathon (490 BC) to Fontenoy (1745), might be boggy, as at the Battle of Agincourt (1415), or rolling hills, as at the Battle of the White Mountain (1620). The battles of the 19th century still had something of this idealised landscape, even if the British infantry at Waterloo were concealed by Mont Saint Jean, and in August 1870 the plateau of Gravelotte was cut across by a deep ravine. However, throughout history, war and tactics have also been synonymous with sieges, fortresses, and even ambushes and guerrilla warfare.

The autumn manoeuvres prior to 1914 perpetuated this type of theorised combat, on an exposed plain, with no protection or cover, because the doctrine was concerned with attack. Charges like at the Pratzen Heights (Battle of Austerlitz, 1805) were a tactic devised to bring about a decisive, rapid victory. However, from 1914 onwards, both the armaments and the sheer numbers of troops deployed would have a profound impact on war zones and their associated landscapes.

THE ERA OF PLAINS, HILLS AND PLATEAUX

The offensive phase of summer 1914 took place on arable plains and grasslands, where regiments were deployed against the German troops in the Ardennes, the Pays Haut, the Woëvre, the Lorrain Plateau and Haute Alsace. Coinciding as they did with the month of August, poet Charles Péguy’s metaphor of “ripe ears and harvested corn” came to represent the physical setting of these early offensives, which were soon halted by a combination of well-positioned German machine guns and formidable heavy artillery, well concealed behind the slopes and hillocks of the Lorrain Plateau and the Pays de Briey. The Battle of the Marne, which followed the “initial setbacks”, as they were described by General Joffre himself, in fact took place south of the river, on the arid plains of Champagne, in the valleys of the Grand and Petit Morin, and in the Saint Gond marshes, where the French and British armies halted the German offensive.

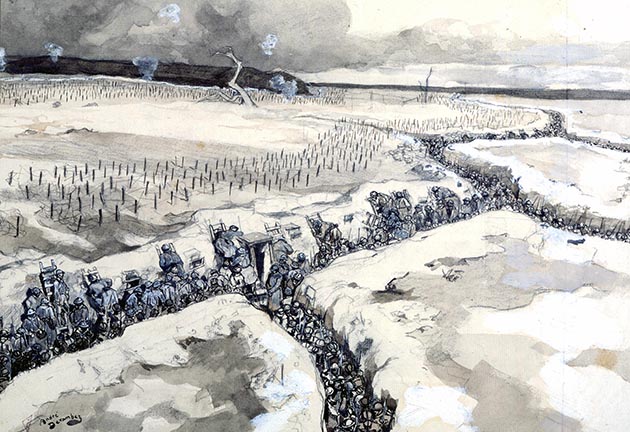

Système de tranchées, watercolour by André Devambez (1867-1944), depicting soldiers in the trenches

just before the assault of winter 1915. © TopFoto / Roger-Viollet

But already another strategy was emerging, which would persist until the end of the war. Using the hills of the Lorrain Plateau, the Germans stopped the 15th Corps at Morhange. Similarly, the offensive on the Grand Couronné near Nancy, part of the Moselle hill system, put a stop to the invasion of Lorraine. Joffre’s manoeuvre in Champagne followed the line of the Meuse hills and the Séré de Rivières system of fortifications, from Toul to the Argonne via Verdun. The hills, limestone hillocks and their buried fortifications would become the setting for the major battles of the static war, a form of siege warfare on a grand scale: Verdun, Bois-le-Prêtre, the Argonne, then the Chemin des Dames, close to the lines of trenches dug by the Germans. Low-elevation limestone hills became insurmountable obstacles under the fire of concealed artillery and machine guns in pillboxes. Assaults on hillsides under enemy fire remain a symbolic image of the battles of Éparges, Champagne and Verdun. The day-to-day landscape for both troops and strategists would see a profound, lasting impact from this new form of warfare: networks of trenches and sunken access routes, destruction of wooded areas, craters, earth laid bare, disappearance of villages and arable land, networks of barbed wire, and concrete pillboxes.

Already a decisive element in the initial operations of 1914, artillery calibres of increasing size would be deployed in large numbers. Besides the well-known French 75mm field gun and the less well-known German 77mm equivalent, both capable of neutralising platoons by firing shrapnel shells (named after the British army officer who invented them), fixed artillery ranging from 110mm to 520mm would use every available gun, including naval guns, to attempt to destroy dug-in enemy positions in preparation for what was to become the obsession of both commands: breaking through the unbroken front.

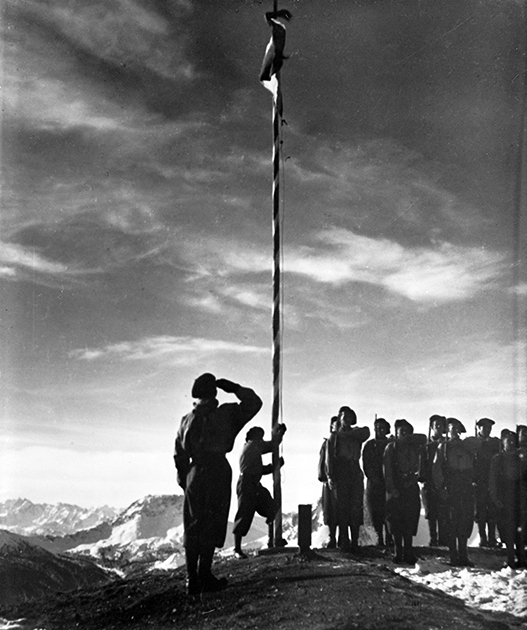

French chasseurs alpins hoisting the flag, at the start of the Second World War. © A. Harlingue / Roger-Viollet

FORTIFIED LANDSCAPES

Throughout history, battlefields and fortified positions have been the subject of reconnaissance watercolours. This continued into the First World War, combined with photographic panoramas, aerial photographs and plans of the combat zones which comprised the trench networks. Air forces naturally contributed to changing the vision of the landscape. But no assault tactics in use at that time, in particular exposed platoon charges into no man’s land (going “over the top”), would succeed in securing any lasting breakthrough. In the spring of 1918, taking advantage of weak points where troop numbers were reduced, the Germans succeeded, only to be stopped in the countryside of Brie and the Tardenois, by a successful counter-attack supported by Renault FT-17 tanks.

The end of the war left an utterly devastated landscape in the battle zone, which was redeveloped in a variety of ways: many landscapes saw a return to agriculture, as in Flanders, Artois, Picardy and Lorraine, while some were turned into state-owned forests, as around Verdun; in others, like Verdun, Bois-le-Prêtre and the Hautes Vosges, the ruins were preserved, while in others still, monuments were erected on important sites of the conflict. Once the war was over, the armies occupied the left bank of the Rhine. The river became central to the occupation of the Rhineland, with its key sites with their characteristic architecture: the great bridges of Mayence, Mannheim and Kehl, together with the legendary, romantic and mythical landscapes of the schistose massif, Mäuseturm and Lorelei.

In the colonies, Morocco and French West Africa, fighting against tribal uprisings would lead to the mythology of the Foreign Legion and Troupes Coloniales, with the corollary of an imaginative world of rocky mountains and desert landscapes, remote outposts and little forts, popularised in literature, song and film.

From occupation of the Rhineland to surveillance of the Maginot Line, the 1930s and the “Phoney War” featured landscapes of heavy fortifications in reinforced concrete, medium-range artillery scattered across Lorraine and Lower Alsace, and pillboxes dotted along the Belgian border and the Saar. A long wait in wooded settings on ancient, levelled massifs of sandstone and schist of the Ardennes, the Pays Haut, the Warndt depression, the Pays de Bitche and Outre-Forêt, clearings and pastures that would see the German offensives thwarted time and again, and where the front would be established, as in the First World War, only under cover.

The men formed “crews” in set-ups reminiscent of warships. Evacuated ghost villages between the Maginot Line and the border, and on the French side of the Siegfried Line, were used for stationing troops, who received a helping hand in the winter of 1940 from paramilitary groups of chasseurs à pied.

1940-1945: CONTINUOUS ADAPTATION TO NEW LANDSCAPES

The Battle of France, beginning on 10 May, would not be tied to these obstacles. For the French army, it was to be a succession of defensive fighting on the arable plains of Belgium, Artois, Picardy, Champagne, the Loire Valley and their fringes. Plains were the setting for meeting engagements in Belgium, at Hannut, and in France, at Stonne: tank battles, in which the lines advanced without cover, shooting on sight, and which were dominated not only by German tanks, but by their 88mm anti-aircraft artillery, used as anti-tank guns. The last attempts at counter-attack would be made by the 4th Armoured Division at Montcornet, then, more sporadically, by isolated battalions, sometimes re-equipped with tanks, as at Montcontour in Vienne or Faucogney in the Vosges. The Meuse, hemmed in by the steep-sided schist valleys of the Ardennes, was crossed by the Pionniers and Panzergrenadier on 14 May. Allied command would continually seek to regain a foothold on river after river, deep in this land of plains with no other obstacles. Attempts were made to gain a foothold on the Somme, the Aisne, the Oise, then the Loire. The tactics were the same: blocking and blowing of bridges, tank and gun ambushes, resistance from officer cadets of the Saumur Cavalry School, in a ratio of one to 20, around Ponts-de-Cé and Île de Gennes. The last shots were fired on the Charente and the Rhône.

In the Alps, the setting was different. The ski scouts, infantrymen and artillerymen stationed at the outposts and forts along the border passes and ridges of Tarentaise, Maurienne, Briançonnais and Queyras engaged in defensive fighting at heights of over 2 000 metres above sea level. Mule tracks and snow-capped peaks formed the backdrop for these Alpine troops, at a time of year when weather conditions remained wintry at these altitudes. The forts of Redoute Ruinée, Turra, Janus and Mont Agel resisted; a line of well-spaced 280mm Schneider howitzers above Briançon destroyed the turrets of the Italian fortress of Mont Chaberton with carefully placed shots. However, attacked from the rear by the Germans, the Army of the Alps would also have to fight in the cluses, narrow, steep-sided passages linking wide valleys in the Alpine foothills, at Bellegarde, Culoz and Voreppe. Landscapes of grandiose limestone folds, for a handful of troops resisting invasion.

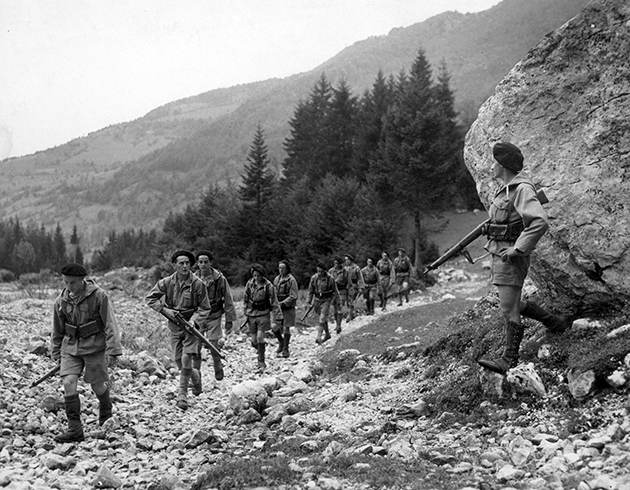

French soldiers who have taken to the hills as a sign of resistance, advancing along a mountain path, 1944. © Alinari / Roger-Viollet

After the armistice, the war would take Free France to desert lands, in Ethiopia, Egypt, Chad: vast distances, expanses of stones and sand, flatlands but also escarpments, wadis and oases were the theatres of operations for the Free French Forces. Organisation, a feel for the terrain and a spartan lifestyle would be the conditions for victory against a less well-adapted enemy.

The fighting of the Resistance also had its landscapes: the bocage and moorlands of Haut Limousin, with their sparse roads, formed an area known as ‘Little Russia’, unreduced in size for four years. This rural southwest was the scene of operations of the Free French paratroopers of the SOE, and also the mission of repression waged by part of the SS Das Reich division, along a road of massacres from Montauban to Tulle and Oradour. The same was true of the maquis in the foothills of the Pyrenees and in Ariège, where the steep terrain, local population and Spanish refugees joined forces against the occupier.

In the Alps, fortresses were built to station German troops in the Prealp massifs of Glières and Vercors, and in Beaufortain. The inverted synclines of the Prealps would prove poor refuges, since they were accessible by road from the valleys. Wilder and more isolated, the small granite massif of Beaufortain, with the Col des Saisies for parachute drops, was spared the assaults of the Mobile Reserve Groups and Alpenjäger.

The aerial dimension of the reconquest of Europe and German stalling tactics would lend a unique physiognomy to the operations following the Normandy Landings: much of the fighting took place in towns and cities in ruins - Saint-Lô, Brest, Aix-la-Chapelle, Stuttgart - or along improvised defensive lines, taking advantage of opportunities for ambush - the Normandy bocage, the Moselle hills, and the forests of the Vosges and Ardennes.

But, ultimately, the most striking spatial aspect of this extraordinary conflict was discovered mainly with the advance of the Allied troops: the vast camps of prisoners of war, Spanish Republicans, forced labourers, deportees and extermination, covering Germany, its annexed regions and even the defeated countries, marked the landscape with their barbed wire, expanses of huts, incessant movements of convoys and teams of workers clocking on at neighbouring factories. The concentration camp system left its mark, both in the consciences of the liberators and across the plains and plateaux of northern Europe.

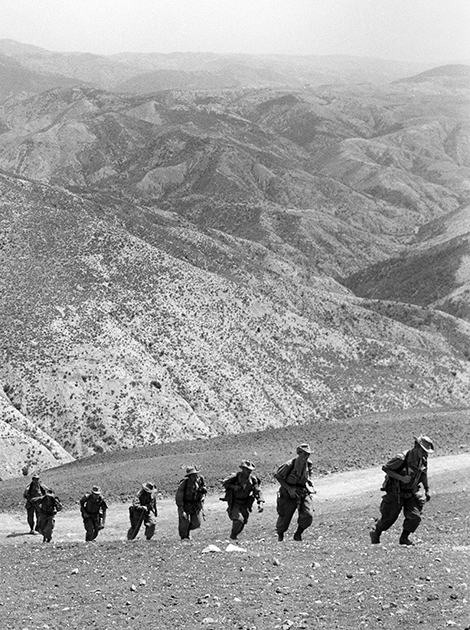

After 1945, the theatres of war moved overseas, first to the rocky peaks of Asia, with their tropical vegetation and monsoons, and the long colonial roads and paddy fields of the floodplains of Indochina. Troops had to be alert to guerilla attacks, stay among the local population, spy, avoid death traps, maintain supply lines, live and fight in the heat and humidity. Then came the Algerian War, fought against the backdrop of the jebel, the mountains of North Africa, and in the labyrinthine streets of the ancient citadels, or kasbahs. These extensive or restricted landscapes would be a refuge for insurrection.

FROM PADDY FIELDS TO MOUNTAINS, DESERTS TO URBAN AREAS

Since 1962, overseas operations have been to the fore: the Sahel, the desert, the bush, the featureless landscape of the African plateau, were the habitual environment for a tactic involving marines or mobile legions equipped with light armoured vehicles, backed up by Jaguar support aircraft, which until the 1990s was sufficient to control a whole country.

Harkis of the 158th Infantry Battalion in the Mascara sector during the Algerian War, summer 1961.

© J-P. Laffont / Roger-Viollet

Closer to home, operations under the aegis of the UN or NATO have put our troops in intervention situations in dilapidated or ruined modern cities, facing militias equipped like regular armies (with tanks and heavy artillery). Beirut, Sarajevo, Kabul and Syria offer every possible opportunity for ambushes and car-bomb attacks. Afghanistan has its long, steep roads, its immense valleys, its redoubts of insurrection. The Middle East offers theatres of flat desert and Mesopotamian floodplain, involving combat over huge distances using long-range artillery or air power.

The landscapes of combat zones have thus evolved a great deal, both in terms of the size of the theatres and their location. From the plains, hills and plateaux of northern and northeastern France, mechanised warfare developed combat zones centred around strongpoints, bridges and urban areas, while, in overseas theatres, deserts, jungles and citadels formed the backdrop for counter-insurgency and zone-control operations.

1982: the French army in Lebanon. © F-X. Roch / ECPAD / Défense

These new landscapes have also forced tacticians either to adapt to them, or to develop new operational frameworks. The defence of national interests and international engagements have spread across the world, far beyond the plains of northern France. These landscapes preserve the traces of those conflicts in three ways: through the memories of combatants and actions of remembrance, with commemorations held in situ around a stela or memorial; through physical marks, ruins and fortifications, with or without shell damage; and through first-hand testimonies like negatives, rebuilt towns, abandoned fields and restored woodlands. To the trained eye as much as to the layman passing on their memories, all of this combines to form the places shaped by the events of our history.

Chief Commissary Nicolas Jacob - Service Historique de la Défense

Personalities

Related articles

- First World War

- La première bataille de la Marne

- La bataille de Verdun

- Le Chemin des Dames

- Le système Séré de Rivières

- Tranchées et boyaux

- 1930 - 1940 La ligne Maginot

- Description, organisation d'un gros ouvrage de la ligne Maginot.

- La drôle de guerre 39-40

- Une bataille oubliée - Les Alpes

- D Day in Normandy

- The Battle of Normandy

- The “Battle of the Hedgerows”

- Provence août 1944

- After the Liberation, rebuild a country in ruins ...

- First world war places of remembrance