The return of the Republic

Contents

6 juin : débarquement allié en Normandie.

8 juin : libération de Bayeux.

9 juin : massacres de Tulle.

10 juin : massacres d'Oradour-sur-Glane.

14 juin : débarquement du général de Gaulle à Courseulles-sur-mer, dans le Calvados . discours de Bayeux.

19 juillet : libération de Caen.

20 juillet : massacres de Vassieux-en-Vercors.

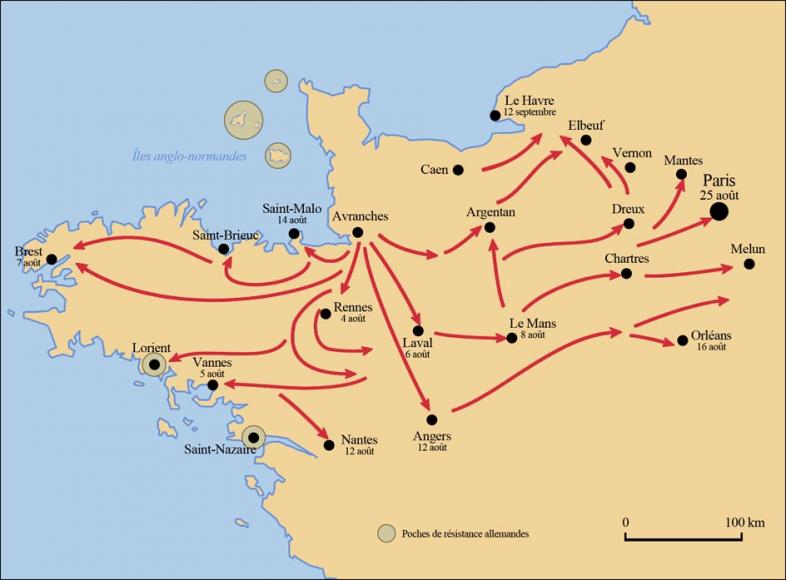

1er août : débarquement de la 2e DB (division blindée) du général Leclerc à Utah Beach.

4 août : libération de Rennes.

5 août : libération de Vannes.

8 août : libération du Mans.

12 août : libération d'Angers et Nantes.

15 août : débarquement de la 1re armée de De Lattre et de la 1re DFL (division française libre) en Provence.

16 août : exécution de 35 résistants par les Allemands près de la grande cascade du bois de Boulogne . libération d'Orléans et Tulle.

17 août : départ de Drancy du dernier convoi de déportés juifs . libération de Cahors.

20 août : libération de Pau et d'Albi.

21 août : libération de la poche de Falaise.

22 août : libération de Grenoble.

25 août : libération de Paris, entrée du général de Gaulle dans la capitale.

26 août : Descente des Champs-Élysées par le général de Gaulles et des personnalités de la France Libre et de la Résistance.

27 août : libération de Toulon.

28 août : libération de Marseille.

31 août : transfert du siège du Gouvernement provisoire de la République française d'Alger à Paris.

3 septembre : libération de Lyon.

7 septembre : départ de Philippe Pétain et de Pierre Laval pour l'Allemagne.

12 septembre : jonction des armées de l'ouest (2e DB) et du sud (1re DFL et 1re Armée française) à Monbard, dans la Côte-d'Or . début de la campagne des Vosges . libération du Havre.

19 septembre : intégration des FFI (forces françaises de l'intérieur) dans l'armée régulière.

30 septembre : création de l'Agence France-Presse (AFP)

23 octobre : reconnaissance du GPRF par les Alliés.

28 octobre : dissolution des milices patriotiques.

2 novembre : début de la campagne d'Alsace.

20 novembre : libération de Mulhouse.

23 novembre : libération de Strasbourg.

Summary

DATE : 10 – 31 August 1944

OUTCOME : Liberation of Paris

FORCES PRESENT : US Army V Corps commanded by General Gerow

French 2nd Armoured Division commanded by Général Leclerc

Forces françaises de l'intérieur (FFI)

German garrison commanded by General von Choltitz

De Gaulle considers that Paris—the secular heart of the French sovereign State—occupied by the Germans since 14 June 1940, embodies the "remorse of the free world." Since the Normandy Landings on 6 June 1944, the French capital has been a key strategic and political focus.

Paris, the "heart of the captive country", is of paramount importance in the final battle. For de Gaulle, it is a prerequisite for regaining national sovereignty at both national and international levels.

On 3 June 1944, the French Committee for National Liberation (Comité français de la liberation nationale - CFLN) in Algiers becomes the Provisional Government of the French Republic (Gouvernement provisoire de la République - GPRF), which shows the Allies that there is a wartime government led by General de Gaulle. "National liberation cannot be distinguished from a national insurrection”, he had stated in April 1942. De Gaulle repeated this in 1943 and again in 1944, while insisting on the fact that it had to be carried out in an orderly and controlled manner. This was indeed the aim of the measures implemented in Algiers concerning the organisation of civil and military powers devoted to the seizure of power and the restoration of republican legality in metropolitan France during the Liberation. In addition to the restoration of the Republican State, the Order of 21 April sets out the role of the Military Committee for Action in France (Comité militaire d'action en France - COMIDAC), presided by de Gaulle, in "conducting operations in occupied territories", with General Koenig, head of the French Forces of the Interior (Forces Françaises de l'intérieure – FFI), as the military representative in London. One month before, it had been announced that COMIDAC was taking command via a clandestine national military delegate—General Chaban-Delmas—who was appointed in April.

Leclerc avec Rol-Tanguy accueillant le général de Gaulle à la gare Montparnasse, 25 août 1944.

© coll. privée

Paris— sovereignty at stake

Paris regains its status as France's political capital in 1943 under the impetus of Jean Moulin, who establishes the headquarters of a clandestine counter-State by federating the resistance and creating the Conseil de la Résistance in an association of movements, trade unions and political parties. Despite being weakened by the death of Jean Moulin, the General Delegation asserts its authority as a product of the State during the Liberation. Alexandre Parodi, a member of the Council of State, appointed in April 1944, is promoted to a "member of the GPRF and Commissioner of State delegated to the occupied territories" on 14 August. As the direct representative of de Gaulle, he makes preparations for the establishment of the provisional government in the capital city. The National Resistance Council (Conseil National de la Résistance – CNR), presided by Georges Bidault since 1943, establishes itself as the Resistance's most representative body and asserts its independence. It has joined forces with the Communist-dominated Military Action Committee (Comité d'action militaire - COMAC), with a view to leading the military action in France. Despite participating in the GPRF since April, the Communist Party seeks to exert an influence in the French capital with its members in positions of power, which causes concern in the GPRF. Neither Chaban-Delmas nor Parodi were worried about the Communists seizing power.

FFI à l’affut derrière une barricade, Paris, août 1944.

© DR

Paris, concerned about the spectre of its revolutionary past, is subject to a special Order governing its municipal and département-level administration. The Prefects of the Seine and of the Police are appointed in compliance with the principle of one member of the Resistance and one member of the Free French Force. At the Prefecture of the Seine, the Resistance member Marcel Flouret (1892-1971) is appointed on 28 April 1944. He takes up his duties at the Hôtel de ville (City Hall) on 20 August, on the date of the occupation of the Maison Commune, to ensure the continuity of municipal services. On 17 June, de Gaulle appoints Charles Luizet, who had joined the Free French force on 18 June 1940 and proven his merits as Prefect of liberated Corsica, to the post of Prefect of Police.

Amené à la Préfecture de police, un canon antichar pris aux Allemands par les FFI – policiers ; certains d’entre eux portent le brassard réglementaire.

© Gandner Musée du général Leclerc et de la Libération de Paris/Musée Jean Moulin (Paris Musées)

From the international perspective, de Gaulle considers it to be vital for French troops to go into combat in Paris before the Allies. He is worried about the Americans establishing an Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories (AMGOT) as in Italy. In December 1943, he gives General Leclerc and the French 2nd Armoured Division the task of liberating Paris and establishing a base for a French government. The enthusiastic welcome given to de Gaulle by the people of Bayeux on 14 June 1944 and the appointment of the civil authorities, stave off the threat of an AMGOT. In mid-August, the breaching of the Falaise pocket and the landings in Provence cause Eisenhower to postpone the liberation of Paris and bypass the city in order to prioritise the efforts on the Eastern Front. He is anxious to avoid Paris becoming a “new Stalingrad” due to the logistical problems associated with resupplying the population.

The road to insurrection (14 July-18 August 1944)

For the Germans, although the Battle of Normandy is their priority until mid-August, the City of Light remains a powerful symbol for Hitler who puts General von Choltitz in charge of Gross Paris (Greater Paris) with the task of holding the city down to the last man. The forces (20,000 men and around 20 tanks) consist of administrative staff and elderly soldiers lacking in motivation, in addition to other soldiers and SS troops that spread terror, as evidenced by the mass graves at the site of massacres (waterfall in the Bois de Boulogne and Mont Valérien. Remaining faithful to their strategy of repression, the occupying force continues the deportations: the last convoys leave the Paris region on 31 July and again on 15 and 17 August, taking 3,451 Jews and resistance members to the death camps. Deeply concerned about the fate of political prisoners in Paris, the Swedish Consul—Raoul Nordling—negotiates with von Choltitz and the SS to obtain the release of 2,000 people in exchange for German prisoners. In mid-July, the Communist party, COMAC and the Paris Liberation Committee (Comité parisien de la Libération - CPL)—created in October 1943 by André Tollet, a Communist Resistance fighter and trade union activist—decide they want to make the French national holiday on 14 July a day of demonstrations to mark the start of the insurrection. The tension rises between activists and the advocates of a waiting game. The demonstrations are followed by insurrectionary strikes called by railway workers on 10 August, followed by the police force on 15 August and the city's civil servants, postal workers and nurses on 18 August. They are carried out in response to General de Gaulle's call for action on 7 August: "French people standing proud and in combat [..] "Refrain from doing any useful work for the enemy." On 18 August, the events in Paris can no longer be controlled from outside the city. Despite Koenig's instructions—brought from London by Chaban-Delmas—to slow down the movement, the insurrection is now underway, as observed by Alexandre Parodi. "Paris was ripe for a major uprising". In Paris, the chain of command had been simplified: Colonel Rol-Tanguy (Communist, FTPF), commander of the FFI in the Ile-de-France region and a renowned military leader, assumes the military leadership of the insurrection involving the armed forces of the Resistance, the FTPF (Francs-tireurs et partisans francais – French Irregulars and Partisans) led by Charles Tillon, a national leader, and all government forces, gendarmes and fire-fighters that Parodi has placed under his command in the interest of unity and efficiency.

Leclerc examinant le plan de Paris avec son supérieur le général Gerow, 25 août 1944.

© coll. NARA, Musée du général Leclerc et de la Libération de Paris/Musée Jean Moulin (Paris Musées)

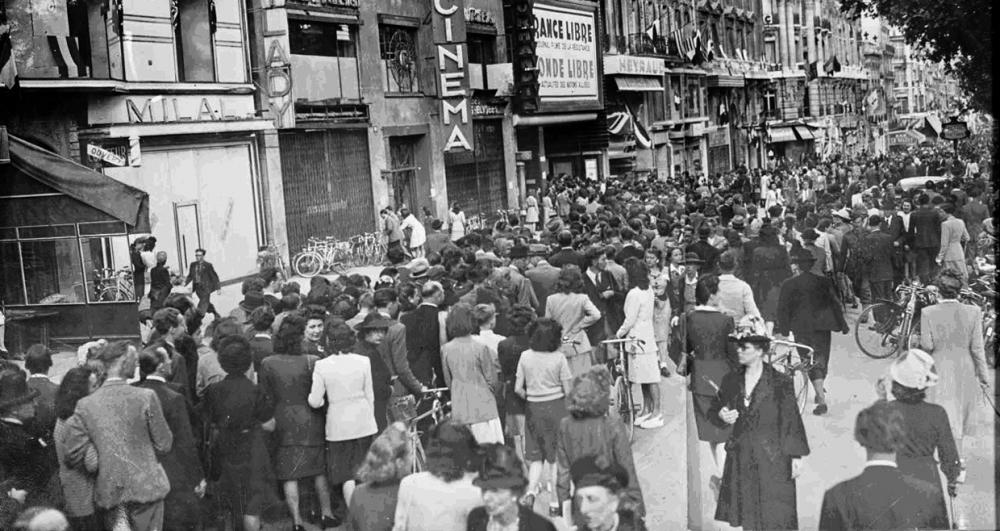

General mobilisation! (19 August-23 August 1944)

The spontaneous occupation of the Préfecture de police (Police Headquarters) on 19 August by 2,000 officers supported by Rol-Tanguy, comes soon after the general mobilisation order, typed out by his wife Cécile, which clearly sets out everyone's roles: patrols and the occupation of public buildings and factories… culminating in "opening up the road into Paris for the victorious Allied armies and welcoming them to the city". The lack of arms to counter German attacks leads to the negotiation of a truce by the Swedish Consul with von Choltitz. This initially applies to just the Police Headquarters but is subsequently extended to the entire city. Backed by Parodi, Chaban-Delmas and Hamon of the CPL, who see it as a way to await the arrival of the Allies, the truce is rejected by Rol, COMAC and the CNR, who denounce it as a form of demobilisation and consider it to be a trick used by the enemy to facilitate the withdrawal of their forces from Normandy. The truce is never observed and is broken on the 21st. In the meantime, policemen, members of the Resistance and young members of national teams manage to gain access to the City Hall, in the name of the provisional government. There is a resurgence of the mobilisation with the building of nearly 500 barricades – an exceptional occurrence in France during the summer of 1944. The population of Paris rediscovers an age-old tradition. Although the insurgents are isolated due to the difficulties in communicating with London and Algiers, the "Radiodiffusion de la nation française" public radio station and the written press, which emerged from its underground existence on 21 August with dispatches provided by the newly created “Agence Française de Presse” press agency, stir people into action.

Le général de Gaulle est accueilli par les représentants de l’État installés à la Préfecture de police. (de g. à dr.) Charles Luizet, Achille Peretti, commissaire de police et Alexandre Parodi, ministre des territoires occupés.

© Service de la mémoire et des affaires culturelles - SMAC- de la Préfecture de police.

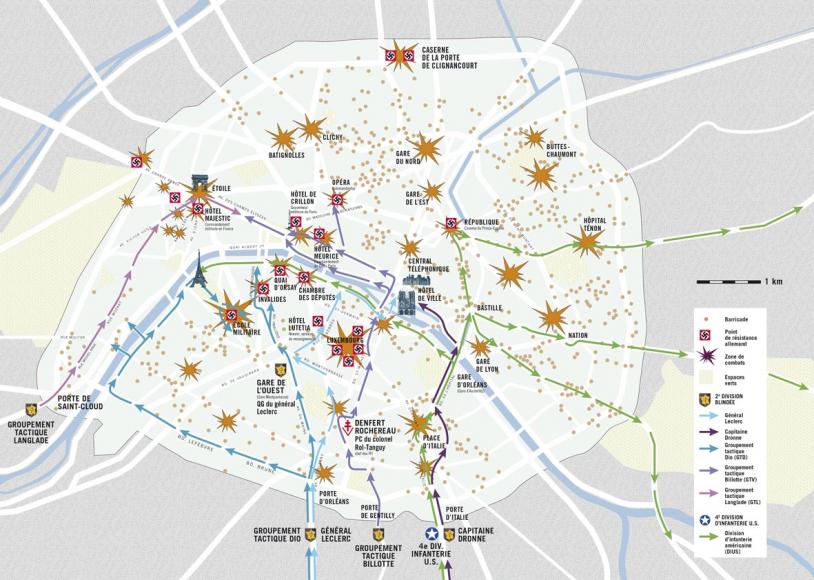

From its headquarters at Denfert-Rochereau, the FFI's senior command staff, in addition to ordering guerrilla operations, organises the surveillance of the drinking water network in order to prevent any poisoning by the enemy, which has also mined certain sites: the telephone exchanges on the Rue des Archives (3rd arrondissment [district]) and Saint-Amand (15th), the Senate, the Saint-Cloud, Alexandre III and Neuilly bridges, the Cercle militaire Saint-Augustin and certain roads, in addition to the Fort de Charenton and the Château de Vincennes. The burning of the Grand Palais by the enemy on 23 August, in reprisal for the attack on a German column by the police and FFI, leads to fears of plans to destroy historic monuments. The fears are fuelled by the retreating German units and tanks, acting as temporary reinforcements.

Advance of the French 2nd Armoured Division (23-24 August)

General Leclerc grows increasingly concerned when the insurrection is announced on 18 August and even more so when he hears that the Americans are bypassing the city. Paris has been his obsession since mid-August and upon hearing of the attachment of his division to General Gerow's US Army V Corp, he protests to General Patton (commander of the US 3rd Army) and then to Hodges (1st Army). Without waiting for confirmation of the order, his musters his unit and on 21 August, sends a light detachment (of tanks, armoured cars and infantry) commanded by Major de Guillebon— a member of the Free French from Chad—to Versailles, with orders to enter Paris if the enemy withdraws. Messages delivered by emissaries sent by the Resistance to the Allies and the insistence of de Gaulle, who threatens to order the 2nd Armoured Division to march on Paris, finally prompt Supreme Commander Eisenhower to send the 2nd Armoured Division and General Barton's US 4th Infantry Division to the capital city. This reflects a sudden pang of conscience in the Americans who want to save Paris.

After making quick progress on 23 August, the advance is halted on 24 August when the 2nd Armoured Division encounters strong German resistance. Parodi, Chaban-Delmas and Luizet urge Leclerc and his division to enter Paris. Leclerc's response, in defiance of the German anti-aircraft defence (“flak”) is to send a Piper Cub (small reconnaissance aircraft) to drop a message on the Police Headquarters proclaiming “Hold fast, we're coming”. That evening in Antony, instead of entering Paris with his unit as planned, Leclerc's anxiety reaches a peak upon learning that German reinforcements are on their way from northern France. Realising that one of his first companions-in-arms—Captain Dronne—is the ideal man for the situation, he orders him to “storm into Paris”. At 9:20 p.m., the tanks and half-tracks of “La Nueve” (Ninth Company), manned mainly by Spanish Republicans, reach the Place de l'Hôtel de Ville, to thunderous applause. As the news spreads, church bells start ringing. Shortly afterwards, the General issues his orders: "enter Paris by the main routes, head right to the heart of the capital, take the bridges […] go directly to von Choltitz and get him to surrender".

"Paris liberated" (25 August 1944)

On 25 August, while his three units are entering Paris, Leclerc, in his command car with Chaban-Delmas as his guide, makes his entrance via the Porte d'Orléans and heads through a cheering crowd to his headquarters at the Montparnasse train station. Joined by General Gerow—his American commanding officer—he sets out his battle plan. After congratulating the railway workers: “You've done a fine job”, he then makes his way to the Police Headquarters to meet Barton. In the Prefect's billiard room—headquarters of Leclerc's assistant Colonel Billotte—Choltitz, now a prisoner, arrives at around 3:00 p.m. to sign the surrender agreements for the German troops. Luizet, Chaban-Delmas, Kriegel-Valrimont of COMAC and Rol-Tanguy are also present. Taken to the Montparnasse headquarters in Leclerc's command car, Choltitz sends around twenty orders of surrender to his units which are still fighting. At this time, Leclerc, at the request of Chaban-Delmas and Kriegel-Valrimont, authorises Rol-Tanguy to sign one of the copies of the agreement in which the role of members of the “interior Resistance” in the fighting is acknowledged. In a face-to-face discussion with von Choltitz, Leclerc forces him to do what is necessary to resupply the population, pending the arrival of allied food aid. Leclerc's men, with the support of the FFI, wear down the German defences. In the meantime, the 4th Division is in action in the eastern part of the city. The fighting continues in the suburbs in the evening of 25 August.

At just before 5:00 p.m., Leclerc and Rol greet the head of the provisional government in a liberated city that remains intact. De Gaulle has decided in advance how the events will unfold: "The idea is to bring people together in a single national spirit, but also to immediately reveal the embodiment and authority of the State". Leclerc submits his report. There has been no power vacuum. Having been annoyed that very morning by a text proclaiming the CNR to be the sole authority, de Gaulle reprimands the commander of the 2nd Armoured Division for having allowed Rol to sign the agreement. Nevertheless, he acknowledges the role of the FFI and, on 18 June 1945, makes Rol-Tanguy a Compagnon de la libération.

He returns to his post of Secretary of State for War—a post that he had occupied in the last government of the 3rd Republic—thus demonstrating the continuity of the State. With the war not yet over, the President of the provisional government also wishes to make it clear that he is the Supreme Commander of the armed forces. He then heads to the Police Headquarters to meet the provisional representatives of the State: the Prefects Flouret, Luizet and the General Delegate Parodi. It takes considerable persuasion by Luizet before de Gaulle agrees to meet the members of the CPL and CNR awaiting him at the City Hall (Hôtel de Ville). After Marrane and Bidault, he delivers the speech of a head of government who needs no endorsement by anyone, other than the sovereign population. "Paris outraged, Paris broken, Paris martyred but Paris liberated, Paris liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies."

De Gaulle sur les Champs-Élysées (à gauche) Le Troquer Georges Bidault, Alexandre Parodi, Achille Perretti, colonel de Chevigné, (à l’arrière) les généraux Koenig, Leclerc et Juin, (à droite) le FFI Georges Dikson.

© Serge de Sazo. Musée du général Leclerc et de la Libération de Paris/Musée Jean Moulin (Paris Musées)

A Republican government (26 August-13 October 1944)

When asked by Bidault to proclaim the Republic, de Gaulle dismisses his request out of hand on grounds that the Republic has never ceased to exist. The combat carried out since 18 June 1940 is in keeping with Republican principles. The Order of 9 August 1944 does indeed stipulate, in article 1, that “The form of the Government of France is, and shall remain, the Republic. It has never ceased to exist under the law”. It is indeed the outcome of the manifesto of 27 October 1940, issued in Brazzaville, which invalidates the laws of the Vichy government. It is only later that de Gaulle discovers that the CNR and CPL were planning to proclaim this Republic with or without him.

De Gaulle's invitation to the Resistance to join the parade on 26 August, in accordance with the centuries-old tradition of celebrating triumphs and victories, eases the tensions. Nothing is left to chance. De Gaulle—the man famous for making the appeal of 18 June 1940—reviews a detachment of the Régiment de Marche du Tchad (ad hoc infantry regiment of Chad)—a Free French unit of the 2nd Armoured Division, providing a reminder that French weapons were in action from the summer of 1940. The head of the provisional government then places a wreath on the tomb of the Unknown Soldier and sets out on a triumphant procession from the Champs-Élysées to Notre-Dame, which he wanted to act as a “meeting with the people” to whom he entrusts his safety. Accompanied by Parodi and members of the provisional government, Bidault and the Resistance fighters of the CNR and CPL, the Prefects Luizet and Flouret, Generals Leclerc, Koenig,in addition to Juin, Chaban-Delmas and Admiral Thierry d'Argenlieu, he covers the two kilometres from the Place de l'Etoile to the Place de la Concorde on foot to great acclaim from the public. It is one of those rare moments of national unanimity. The man of 18 June—formerly just a voice—now has a face... it is a real consecration. It marks the triumphant reinstatement of the Republican State in the French capital.

The provisional government takes up its functions on 31 August. The priority is to restore order. The parade by two American divisions on the 29th is a show of strength in response to a concern that de Gaulle had discussed with General Eisenhower. On the day before, de Gaulle had signed an Order to disband the FFI's command staff in the liberated regions. Koenig is appointed Military Governor of Paris, General Revers (head of the ORA) is given control of the Paris region and Colonel Rol-Tanguy is responsible for integrating the FFI into the Army of Liberation (Armée de la Libération). At the end of October, the Communist-controlled patriotic militia are disbanded and de Gaulle imposes the authority of the State.

After the Allies announce their recognition of the GPRF on 23 October 1944, there can no longer be any doubt as to the legitimacy of General de Gaulle, in France or abroad. In addition to the government's adoption of an economic development programme, the provisional Consultative Assembly holds its a ceremonious inaugural session on 9 November 1944 at the Senate, where it will sit until the election of the Constituent Assembly on 21 October 1945. France also revives its tradition of consulting the public, whose electoral body is extended to include women and soldiers in the municipal elections of April 1945, followed by the district and legislative elections in November 1945.

From 18 to 30 August (date of the last battles in northern Paris), nearly 5,000 people lost their lives in the fighting: 1,800 people were killed on the French side (156 men from the 2nd Armoured Division and a thousand FFI members including 177 policemen and approximately 600 civilians) while 3,200 Germans were killed and 12,800 were taken prisoner). The liberation of Paris by the Parisians, supported by the 2nd Armoured Division and the Allies, is an act of major historic significance, even though the war is not yet over.

Author

Christine Levisse-Touzé, Director of Research at Paris 4, Director of the Musée du Général Leclerc et de la Libération de Paris and of the Musée Jean Moulin (Paris Musées) museums, Curator-General

Read more

Photo gallery :

The liberation of Paris by Resistance fighters, Parisians and the 2nd Armoured Division

Videos (credits - ECPAD):

Liberation of Paris on 25 and 26 August 1944 – Procession along the Champs-Élysées

Bibliography :

“Libérer Paris” (Liberating Paris), supervised by Christine Levisse-Touzé, with the assistance of Dominique Veillon, Thomas Fontaine, Vincent Giraudier and Vladimir Trouplin, Ouest-France, 2014.

“De Gaulle, la République et la France libre 1940-1945” (De Gaulle, the Republic and Free France 1940 – 1945), Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac, Perrin, 2014 (presented in “Carrefours”).

Articles of the review

-

The event

The liberation and defence of Strasbourg

On 2 March 1941, in Koufra, following a victory that has since become legendary, Colonel Leclerc swore an oath before his men that "we shall not lay down our arms before our colours, our beautiful colours, are flying above Strasbourg cathedral". And now, in the month of November 1944, the 2nd Armour...Read more -

The figure

Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque

He is just 41 years of age in 1943, when de Gaulle chooses him to carry out a vital mission: the liberation of Paris. A Free Frenchman from the outset, Philippe Leclerc de Hautecloque is renowned for his daring and ability to change the course of events.

Read more -

The interview

Jean-Marc Berlière

Jean-Marc Berlière—a historian specialising in the French police and the Occupation—sheds light on the complex issue of the purge of French society immediately after the Liberation.

Read more