Liberating France

Contents

Summary

DATE: 11 May 1945

PLACE: France

OBJECT: Surrender of the German troops that had retreated to Saint Nazaire

OUTCOME: End of the German occupation of France

FORCES PRESENT: France, the Allies, Germany

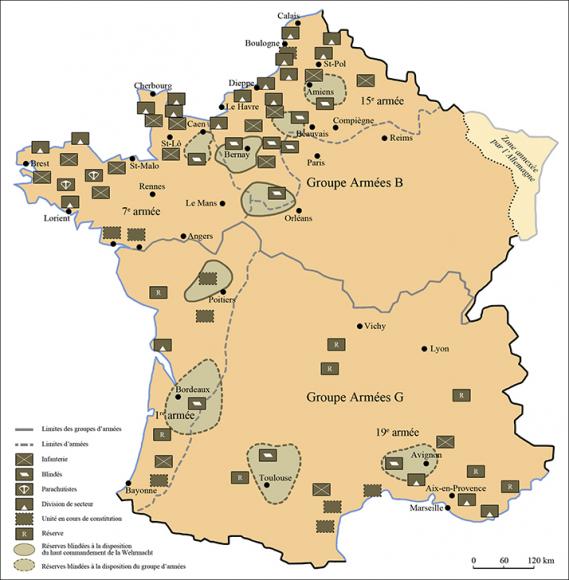

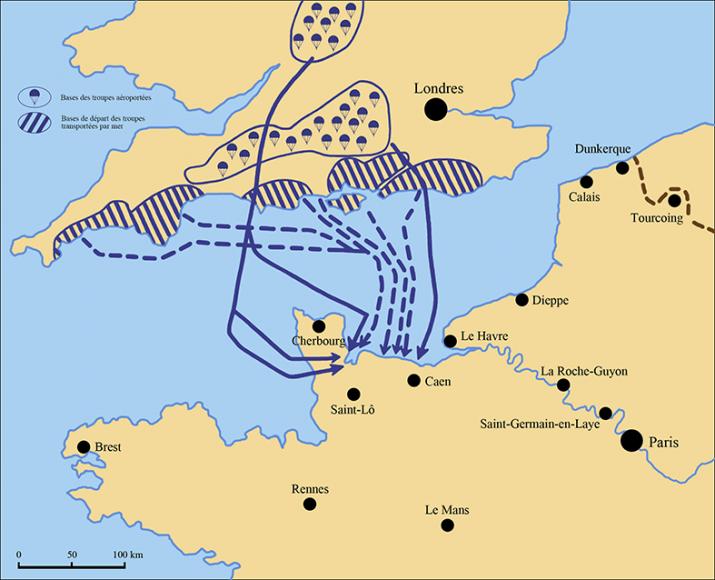

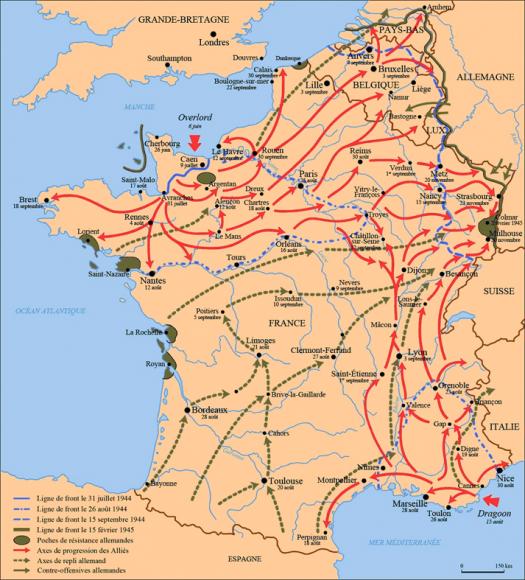

The Allies that landed in occupied France on 6 June and 15 August 1944 undeniably contributed to the country’s liberation, the uprising of the people and the mobilisation of the Resistance. But they did not act alone. The French armed forces were also involved, from the Normandy beaches to the liberation of Alsace.

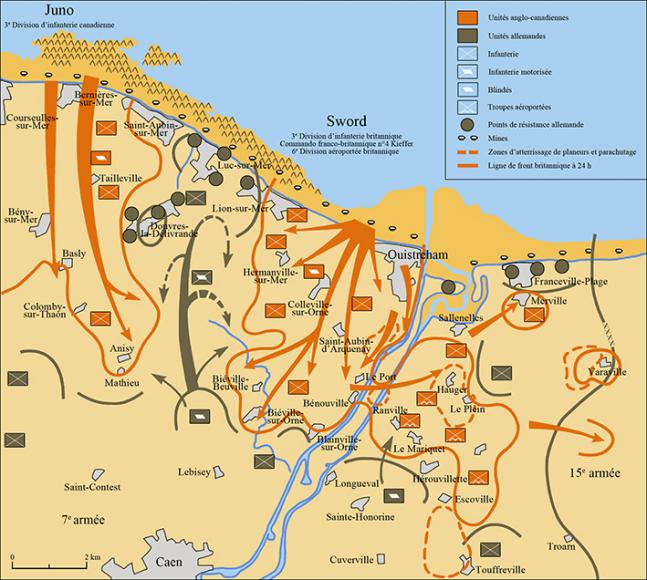

For essentially political reasons, the order of battle of Operation Overlord did not include the main French units. Yet a handful of Frenchmen were among the 156 000 troops engaged in Normandy: 177 naval fusiliers, commanded by Philippe Kieffer. The first to land on Sword Beach, it was their mission to take the fortified position of Ouistreham’s old casino. They achieved their objective mid-morning on 6 June, but by the evening, when it took up a position to the east of the Orne, the Kieffer Commando had lost a quarter of its number.

At sea, off the Normandy beaches, French naval forces were also present. Among the 6 000 Allied ships, 12 French vessels were tasked with ensuring the security of the convoys: the corvettes Aconit and Renoncule were stationed off Utah, the frigates Escarmouche and L’Aventure and the corvette Roselys off Omaha, the frigate La Surprise and the corvettes La Découverte and Commandant d’Estienne d’Orves off Gold; the cruisers Montcalm and Georges Leygues, off Omaha, were tasked with shelling the Longues-sur-Mer Battery, while the destroyer La Combattante, positioned off Juno, protected the Canadians’ right flank; and the battleship Courbet crossed the Channel for its last mission: to be scuppered off Sword Beach, on 9 June, to serve as a breakwater.

Finally, among the 11 600 aircraft involved, a hundred fighters and bombers belonging to the Cigognes, Île-de-France, Alsace-Lorraine, Berry, Guyenne and Tunisia groups took part in air missions before and after D-Day. On 6 June, Squadron 342 (Lorraine group) received the delicate mission of laying a smokescreen off the American beaches to hide the approaching fleet. During the land offensive, the Cigognes, Île-de-France and Alsace groups were employed to protect the Anglo-Canadian sectors of the landings.

French paras jump on Brittany

Yet even before the attack was launched, other French special forces were deployed as part of Operation Overlord, this time in Brittany. In order to consolidate the Normandy bridgehead, the Allies focused their attention on the Breton Resistance, to hold the 150 000 German troops stationed in the region. To that end, French paratroopers of the 4th SAS under Commander Bourgoin were dropped on Brittany to train the maquisards and French Forces of the Interior (FFI) mobilised on the ground.

SAS and maquisards photographed on 20 June 1944, after the surrender of the maquis of Saint-Marcel (Morbihan). © OBL/Musée de la Résistance Bretonne

On the night of 5 to 6 June 1944, lieutenants Marienne and Déplante’s “sticks” (groups of paratroopers) were dropped over Morbihan, between Plumelec and Guehenno, in Mission Dingson. In Côtes-du-Nord, the Botella and Deschamps groups landed near the Duault forest, in Mission Samwest. They preceded a huge airborne operation scheduled for two days later, involving 18 sabotage teams. Although the operation went off without incident, it was more delicate in Morbihan, where the Marienne group landed close to a German position. Quickly surrounded and low on ammunition, the French were forced to surrender. Among the prisoners, a wounded Corporal Émile Bouëtard was shot dead in cold blood. He was the first Frenchman to be killed on 6 June 1944.

Attacked by the Germans on 12 June, the Samwest base was forced to disperse on the evening of the 13th. In Morbihan, the maquis of Saint Marcel went into action as soon as the landings were announced, receiving the SAS soldiers tasked with coordinating the operation of the FFI and Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP), who arrived in number but were often without weapons. Dozens of parachute drops rapidly enabled 3 to 4 000 men to be armed. Alerted by these drops, the Germans decided to act.

On 18 June, German artillery and tanks, backed up by the equivalent of a division, attacked the Saint Michel base, defended by 2 500 men, 140 of them paratroopers. The fighting was violent, and in the evening the maquisards withdrew, leaving about 30 men on the ground. Over several days, a terrible manhunt was carried out across the region. Forty-two Frenchmen including six paratroopers were killed and dozens of others wounded, and villages were set alight. Lieutenant Marienne was shot dead on 2 July, along with five other SAS soldiers.

On 4 August, the order was finally given for a general uprising, as the Americans rushed into Brittany. Despite the failure of the Saint Marcel maquis, the Breton Resistance, aided by the SAS, would go on to make an active contribution to the US victories in Brittany.

The French in the Battle of Normandy

On the British front, the action of Kieffer Commando went on beyond 6 June. Over two months, to the east of the Orne, with no reinforcements, the commando waged a static war a few hundred yards from the German lines. Only the night patrols succeeded in keeping up troop morale, while giving the enemy the impression of greater numbers on the Allied side. The German retreat of 15 August brought a return to mobile warfare. The French engaged in their last fighting at Épine on 20 August, then moved on to Pont-L’Évêque, before returning to England on 8 September 1944. They left behind 17 comrades killed in battle.

General Leclerc and his 2nd Armoured Division land on Utah Beach, Normandy, 1 August 1944. © ECPAD/Défense

Meanwhile, another French unit had gained a foothold in Normandy. After landing on the beach of Saint-Martin-de-Varreville on 1 August, the 16 000 men of Leclerc’s 2nd Armoured Division (2nd DB) came to reinforce the Third US Army, which was preparing to sweep across southern Normandy. The 2nd DB reached Avranches on 8 August, Le Mans on the 9th, then headed back north to take part in closing the Falaise Pocket.

After taking Alençon on 12 August, Leclerc became impatient as he watched the enemy retreat, knowing of the uprising in Paris since 10 August. On 19 August, Colonel de Langlade’s group joined the fighting near Mont Ormel, where the Polish 1st Armoured Division had just closed the net on what was left of the German 7th Army. Three days later, the US command finally gave Leclerc permission to march on Paris. The Battle of Normandy had cost the lives of 860 men, including 135 from the 2nd DB.

“On the march to the capital”

The arrival of the 2nd DB, Allied progress and the landings in Provence greatly encouraged the people of Paris to rise up. It all began with a strike by railway workers on 10 August 1944, joined by the police, which then culminated in a general strike. With the order issued for a general mobilisation on 18 August, the insurgents took over public buildings such as the police headquarters and city hall. After a truce was rejected, the street fighting between the FFI and the Germans resumed with a vengeance. From the 22nd, Paris became covered with barricades, after the call was issued to all Parisians to head for the streets. Realising that the people of Paris could not hold out for long, Eisenhower allowed himself to be persuaded by General de Gaulle to send in the Leclerc Division. The intention had been for the Americans to avoid Paris, but now the French capital was on their roadmap.

Marching towards the capital on 23 August, Leclerc got caught up in serious fighting around Longjumeau, La Croix-de-Berny and Fresnes. He had hoped to reach Paris by nightfall, but on 24 August the furthest forward of his tanks stopped at Pont de Sèvres and Bourg-la-Reine. Impatient, he ordered Captain Dronne to enter Paris and announce the arrival of his division the following day. Around 9.30 pm, the Dronne group reached city hall, much to the surprise of the people, who had come out to cheer the liberators. The next day, Leclerc made a triumphal entry, establishing his headquarters in Montparnasse railway station, while his tactical groups marched on Paris. The act of capitulation signed that afternoon by General von Choltitz was accompanied by some 20 ceasefire agreements for every pocket of German resistance. Some, like the Palace of Luxembourg and Hotel Crillon, would not surrender until late that night.

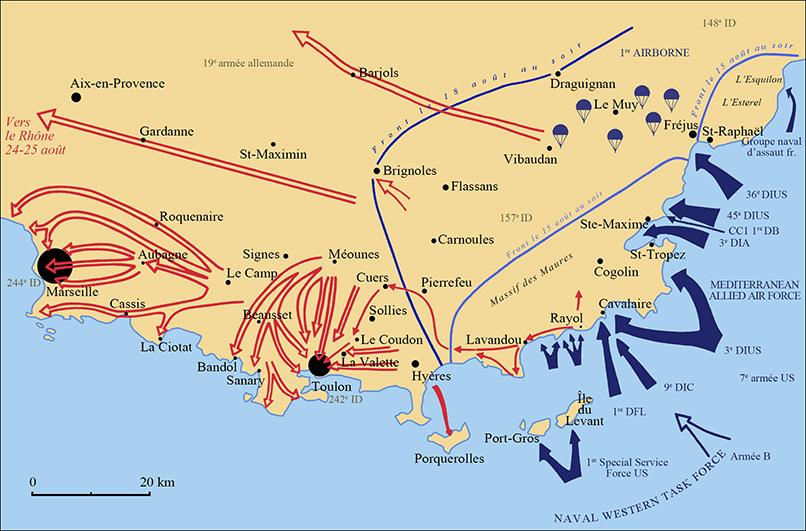

A military and political victory – Paris had not been destroyed and General de Gaulle appeared as the uncontested leader – the liberation of Paris nevertheless had a human cost: 1 000 FFI troops killed and 1 500 wounded, 600 civilians killed and 2 000 wounded, and 130 dead and 225 wounded from the ranks of the 2nd DB. At the exact same moment as the Parisian uprising, on 15 August 1944 the Allies landed in Provence. Their goal? To inflict a decisive blow on the enemy, by establishing a bridgehead at Toulon, before capturing Marseille then advancing towards Lyon to link up with the forces of Operation Overlord. For Operation Dragoon, as it was called, four French divisions that had fought in Italy and three others regrouped in North Africa, made up largely of North Africans, formed General de Lattre’s Army B, which was incorporated in the Seventh US Army.

The French of 15 August

The first French to arrive on the scene were Lieutenant-Colonel Bouvet’s men. Landing at midnight on 14 August, 750 commandos from Africa destroyed the Cap Nègre batteries, before protecting the flank of the landings. At the other end of the formation, 67 French troops of the Corsican Naval Assault Group were forced to divert to Antibes and Nice. Landing between Théoule and Le Trayas, they were caught in minefields and left ten dead and 28 prisoners behind them. The main waves of French troops regrouped on the morning of 16 August around Cogolin and Grimaud, having landed without mishap in Cavalaire Bay and the Gulf of Saint Tropez. Well ahead of schedule, de Lattre advocated a stroke of daring: to take Toulon by surprise, while simultaneously attacking Marseille.

Troops of the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division land in the Saint Tropez area, August 1944. © Auclaire/ECPAD/Défense

Three French divisions converged on Toulon: the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division (3rd DIA) to the north, the 1st Motorised Division to the south and the 9th Colonial Infantry Division (9th DIC) to the east. After three days of fighting, on 23 August the three divisions managed to link up in the La Valette and Mont Faron sector. The first to enter the city, the 3rd DIA units reached the fort of Malbousquet, the railway station and the naval dockyard. Under attack from its sharpshooters and shock troops, the Saint Pierre powder magazine fell, while the Beaumont tower and the forts of Croix Faron and Saint Antoine were liberated with the aid of FFI troops. Meanwhile, the forts of Lamalgue, Malbousquet and Artigues and the Le Mourillon defences gave way to the riflemen of the 9th DIC. On 26 August, the Battle of Toulon ended with the liberation of La Seyne and the capture of 25 000 Germans. In Marseille, the uprising ordered on 20 August led the FFI, in control of the city but short of resources, to call for help from regular troops. On the morning of the 23rd, the 3rd DIA pushed quickly to the heart of the city. Fighting raged in the neighbourhoods of Saint Charles and Notre Dame de la Garde. On 25 August, two groups were sent in against the last pockets of resistance in the port area, Estaque and Notre Dame de la Garde, while the batteries still active in Racati and Cap Janet were shelled. On the evening of the 26th, the fort of Saint Nicolas and the south of the city were finally cleared. On 28 August, 7 000 Germans laid down their arms, 36 hours after the fall of Toulon.

North to Burgundy

As they headed north towards Burgundy, the Allies deployed the French 2nd Army Corps along the Chalon-Dijon-Épinal-Strasbourg corridor, to cut off the German retreat to the east and towards the Rhine. It was a lightning advance. Saint Étienne was liberated on 1 September. Lyon, evacuated by the Germans, was entered on 3 September by the 1st Free French Division (1st DFL). Beaune was liberated on 8 September, Autun on the 9th after violent fighting, while Dijon, abandoned on the night of the 10th to the 11th, in turn found its freedom. Langres was rapidly entered and, despite stubborn resistance in the citadel, was liberated on 13 September. The day before, the 1st Regiment of Naval Fusiliers of the 1st DFL had made contact with the Moroccan Spahis Regiment of the Leclerc Division, at Châtillon-sur-Seine and Nod-sur-Seine. Operations Overlord and Dragoon then came together, four months ahead of schedule. On the 15th, de Lattre received the order to regroup opposite the Vosges for the offensive on Alsace.

French Army and FFI troops parade before city hall after the liberation of Dijon, 13 September 1944. © Auclaire/ECPAD/Défense

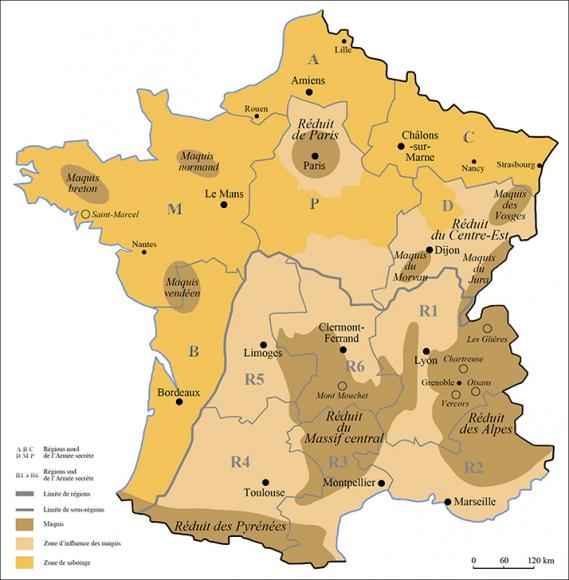

The mobilisation of the maquisards

Other battles were fought by Resistance forces now operating out in the open. In Normandy, in the area around the landing beaches, the maquis above all provided the Allies with valuable information to plan the attacks of Operation Overlord. In Brittany, the maquis of Saint Marcel, which had engaged immediately, did not survive the attack of 18 June. Far from the Norman front, it was above all the larger maquis that focused the attention of the occupier.

The Vercos maquis, Col de la Croix Haute pass, 11 July 1944. © Collection Maurice Bleicher

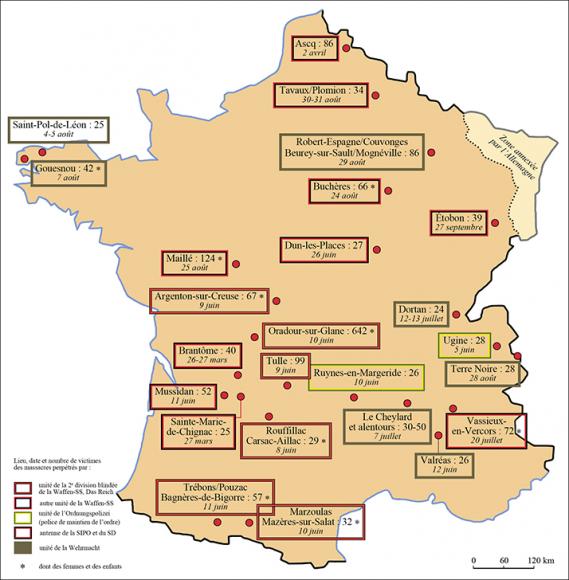

At the announcement of the Normandy landings, 4 000 maquisards headed for Vercors, transformed into an entrenched camp. Confident that reinforcements were on their way, the FFI even proclaimed the “Republic of Vercors”. The enemy’s response to the parachute drops of 14 July was not long coming. On 21 July, 40 gliders were launched over the plateau to support the attacks by the German 157th Infantry Division and the Milice. The plateau was cleared over two days. Until 27 July, terrible reprisals were exacted on the retreating and wounded maquisards, who were executed in the cave of Grotte de la Luire and in the villages of the plateau. The absence of air support, too weak a mobilisation plan and inadequate military resources all contributed to the fate of the Vercors maquis. In the heartlands of the Auvergne, the mass recruitment by the FFI mustered 5 500 fighters on Mont Mouchet and in the Truyère and Lioran massifs. An initial offensive was rebuffed on 2 June 1944 to the south of Mont Mouchet, where 2 700 men were stationed. Galvanised by the landings, on 10 June the maquisards sustained a second attack. That night, they were ordered to retreat to the south, leaving 160 dead. The third attack on the Truyère enclave was launched on 20 June 1944.

After losing 123 of their number, the maquisards escaped their encirclement. Once again, the engagement of the Resistance had proved costly.

From the FFI to a regular army

Evacuated by the Germans in mid-August, many parts of the south of France were liberated by the FFI alone. From Bordeaux, liberated on 28 August, 76 000 Germans retreated towards Dijon. Bringing up the rear, the 20 000-strong Elster Column was harried on all sides. A French column of FFI troops commanded by Colonel Schneider was tasked with cutting off its retreat. The vanguard made it to Dijon, but on 10 September Elster was forced to surrender to the Americans, then, on the 11th, to the maquisards, at Issoudun. In the departments of Pas-de-Calais, Nord, Aisne, Meuse, Meurthe-et-Moselle and the Vosges, the actions of the FFI enabled the Allies to advance across both the Meuse and the Moselle. By late summer, the FFI had become such a major phenomenon that it was decided they should be incorporated into the regular army. Thus, in October 1944, 105 000 men joined the French 1st Army. A further 20 000 fighters would be incorporated into the new 27th Alpine Infantry Division on the Alpine front, while on the Atlanticfront, maquisards and FFI laid siege on the fortified German areas.

Honouring the “Oath of Kufra”

After more than a month of fighting, the French units were exhausted, weakened by losses and severe logistical difficulties. Firmly holding onto their positions, the Germans prevented the Allies from sweeping into Alsace. Launched on 25 September, the French attack had to go around Belfort between Gérardmer and Ballon d’Alsace. After three days of fighting, with the Vosges passes in sight and the breakthrough decided, de Lattre was forced to desist and turn his attention to the extension of the front to the north. The 3rd DIA would engage in serious fighting there, while the 1st DFL, to the south, kept up the pressure. The Americans made such a strong push towards the Bresse that the enemy’s front line was broken on 17 October. Yet the troops appeared so worn out by the fighting and the German resistance that they were unable to exploit it. Nearly 4 000 men were rendered hors de combat, including 800 dead. All hopes of reaching the plain of Alsace faded once and for all when de Lattre decided to redirect his army to the sector of the 1st Army Corps.

General Leclerc greets the troops assembled in Strasbourg’s Place Kléber on 26 November 1944, at a ceremony held following the city’s liberation by his division.

© Castelli/ECPAD/Défense

To carry out their big offensive on Strasbourg and Germany, the Allies had assured the French troops of a significant involvement in Alsace. They attacked on 14 November, liberating Montbéliard on the 17th, then Belfort on the 25th. By 19 November, the 1st Army had reached the Rhine, while Mulhouse was entered on the 20th. On the 24th, Ballon d’Alsace was taken by the 1st DFL. The two army corps had linked up, surrounding nearly 10 000 Germans in the process. Originally reserved for the US Army’s VI Corps, the job of taking Strasbourg was subsequently given to the 2nd DB. Task Force Rouvillois was the first to enter the city, on 23 November. Over two days, Strasbourg was cleared, until the Germans surrendered. By hoisting the tricolour flag above the cathedral, General Leclerc was honouring the oath he had made before his men at Kufra, on 1 March 1941, not to lay down their arms until the tricolour flag was once again flying over Metz and Strasbourg.

Six months after the D-Day landings, the psychological impact of this liberation must not conceal the military reality on the ground: France was far from liberated. The efforts of the Allies now focused on their own troops entering Germany, leaving the French forces with important responsibilities: to lead the defence of Strasbourg, reduce the Colmar Pocket and liberate the enclaves which had formed along the forgotten fronts – the Atlantic pockets and the Alpine front – where the Germans continued to resist. Other battles to be fought to achieve the country’s complete liberation, which came with the surrender of Saint Nazaire on 11 May 1945.

Author

Stéphane Simonnet, researcher at the University of Caen Normandie

Read more

Nous, les Hommes du Commando Kieffer, Stéphane Simonnet, Tallandier, 2019

Les Français dans le Débarquement, Stéphane Simonnet, Orep Éditions, 2019

Articles of the review

-

The event

Il y a 75 ans, la Libération

Read more -

The figure

The Free France Foundation

For the 75th anniversary of liberation, the Free France Foundation brings its network and dynamism into play to organise a rich programme of events to honour and celebrate the Free French who distinguished themselves in 1944 and 1945.

Read more -

The interview

Pierre Simonet

Enlisted in June 1940 in the Free French Forces, Pierre Simonet took part in many campaigns, including Syria, Libya, Tunisia and Italy, before landing in Provence in August 1944. He is today one of only three surviving Companions of Liberation.

Read more

Related articles

- Operation Overlord

- D Day in Normandy

- The French on 6 June 1944

- Battle of Normandy, June-August 1944

- Provence août 1944

- The landings and battle of Provence

- Le choix de la Provence

- Operation Anvil-Dragoon in detail

- Le rôle des FNFL pendant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale

- The Free French Air Force

- Les parachutistes français libres du "Spécial Air Service"

- Battles of Saint-Marcel

- Août 1944 - Libération de Paris

- The liberation of Marseille

- The liberation of Lorraine

- Vers le Rhin

- The 1st Free French Division (DFL)

- La Résistance en actes

- The maquis

- Le Vercors

- Remembering the Resistance: the Vercors maquis

- Maquis du Mont Mouchet